When eric schmidt says 'we're running out of electricity' at a public-speaking event this week, the comment landed like a provocation across Silicon Valley and Washington. Schmidt, the former Google chief executive, estimated the U.S. would need roughly 92 gigawatts of new power to sustain the rapid growth of large-scale artificial intelligence — a number he used to underline the limits of today’s grid. The reaction ranged from investors nervously recalculating infrastructure needs to SpaceX CEO Elon Musk posting a quip on X — "If only there were a company that could do this" — while sharing the clip, a remark that tied the energy debate to renewed talk about space-based data centers.

eric schmidt says 'we're running out of electricity' — the scale of the problem

Schmidt’s 92‑gigawatt figure is striking because it converts abstract machine-learning trends into a common engineering unit: power capacity. For context, he noted the average nuclear plant produces about 1.5 gigawatts, meaning the shortfall he described is equivalent to dozens of new large reactors. The claim is not a literal countdown to blackout, but a policy-sized alarm: AI training and the new generation of inference services are power‑hungry, and growth in model scale, data center density and cooling needs could outpace planned utility expansion.

That pressure shows up in rising data‑center energy use, round‑the‑clock cooling for densely packed accelerator hardware, and the operational cost of running models at global scale. Investors and entrepreneurs have echoed the concern: venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya warned electricity rates could spike if the industry doesn’t change structurally, and major cloud players are already planning hundreds of megawatts of new capacity. Schmidt’s shorthand — eric schmidt says 'we're running out of electricity' — captures both a technical challenge and a political one: how to supply, site and regulate vastly larger compute loads.

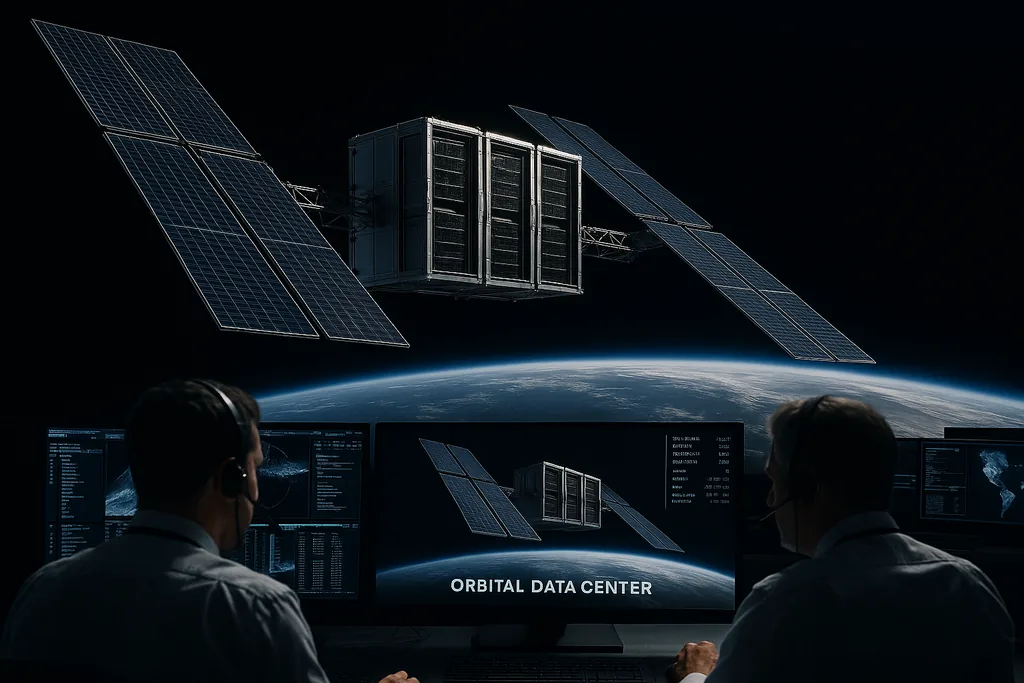

eric schmidt says 'we're running out of electricity' — space data centers as a response

Proponents say orbital racks would be early experiments in reliability, thermal management and radiation hardness rather than immediate replacements for terrestrial cloud regions. Pichai has framed the plan as a "moonshot" with small test systems by 2027 to assess whether compute hardware will survive the radiation environment, how thermal control works at scale and what maintenance models look like. Jeff Bezos and others have floated similar long‑term visions — predicting that, as launch costs fall, the economics of orbital centers could converge with Earth facilities over decades.

How space data centers would work and whether orbit solar can supply them

Space data centers take many shapes on paper: racks in low Earth orbit (LEO), larger stations in geosynchronous orbit (GEO) or platforms on the lunar surface. All variants rely on photovoltaics for primary generation; in sunlight, solar panels in orbit produce more power per unit area than at typical ground latitudes because of absence of atmospheric attenuation. That makes continuous solar a compelling power source in principle, especially for GEO or carefully designed LEO constellations that minimize eclipse time.

Mission planners also have to solve thermal engineering, radiation shielding, fault recovery and in‑orbit servicing. Radiative cooling is powerful, but heat must still be conducted from hot chips to radiators, and radiators add mass and surface area — increasing launch cost. The bottom line: orbit solar is technically feasible as a generation source; converting that into a reliable, economical data center remains a large engineering exercise.

Technical and economic obstacles to lifting data centers off Earth

Space advocates often point to falling launch costs and reusable rockets as the x‑factor that suddenly makes orbital data centers realistic. Elon Musk’s public taunt — "If only there were a company that could do this" — is shorthand for the role SpaceX and similar launch innovators might play. Yet Amazon Web Services CEO Matt Garman has been bluntly skeptical: space centers are "not economical" today. He and others point to the obvious line item — the cost of getting mass into orbit — and to a second constraint: the current cadence of reliable launches.

Beyond launch money, operators face higher engineering bills for radiation‑hardened servers, redundancy and software that tolerates micro‑interruptions. Service models matter too: most cloud users expect predictable latency and large, low‑cost storage; putting compute in orbit may suit specific workloads (long batch training runs, specialized inference at scale, or workloads that tolerate higher latency) but will be a poor fit for general cloud in the near term. There are also regulatory and safety questions around orbital debris, frequency allocations for power beaming, and cross‑border data governance when satellites act like floating national facilities.

Industry dynamics — players, politics and the path forward

The conversation mixes technical debate with corporate signaling. Alphabet’s Project Suncatcher is positioned as a research program — an experiment in racks and thermal systems — while SpaceX’s improvements in launch economics and cadence get name‑checked as enablers. The reported corporate moves tying SpaceX and xAI together add a financing dimension: companies that once competed in adjacent markets are rearranging to capture future compute‑in‑space business models. Meanwhile, cloud incumbents such as AWS publicly emphasize economics and caution.

Policy actors will matter too. Utilities, grid planners and national regulators face real choices about where to prioritize investment: more terrestrial generation and transmission, more demand‑side efficiency, or strategic bets on exotic alternatives such as orbital compute. That is why Schmidt’s comment reads as a policy nudge as much as an engineering note: if the nation takes AI‑scale computing seriously, it will need coordinated planning across energy, space and telecommunications sectors.

Timelines and what to expect next

Space data centers are unlikely to cause an overnight shift in how the world computes. Realistically, expect a staged path: small, instrumented test racks in orbit to measure reliability; better radiation‑tolerant accelerators and fault‑tolerant software; demonstration missions that show thermal control and power management work in practice. If those succeed, the economics could improve as launch prices continue to fall and as certain niche workloads demonstrate value for orbital execution.

In the short term the biggest impact of Schmidt’s remark may be strategic: it focuses attention on the supply side of compute and forces cloud providers, utilities and policymakers to map trajectories for energy and capacity. Whether that leads to orbital data centers, a major push for new terrestrial generation, or a mix of efficiency and distributed computing will depend on engineering outcomes, regulation and where private capital chooses to place bets.

For now, the phrase eric schmidt says 'we're running out of electricity' is less a literal countdown and more a framing device that has accelerated a technical and public-policy conversation about the limits of current infrastructure and the creative — if expensive — alternatives being proposed.

Sources

- Alphabet / Google (Project Suncatcher public statements and Sundar Pichai comments)

- Eric Schmidt public remarks on AI power demand

- SpaceX (Elon Musk statements and company launch technology developments)

- Amazon Web Services (Matt Garman comments)

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!