For decades, planetary scientists have hypothesized that the volcanic landscape of Venus hides vast underground caverns formed by ancient lava flows. A research team from the University of Trento, led by Professor Lorenzo Bruzzone, has now provided the first direct evidence of these subsurface structures by analyzing historical radar data from NASA’s Magellan mission. Published in Nature Communications on February 9, 2026, this study confirms the existence of a massive lava tube in the Nyx Mons region, transforming our understanding of the geological evolution of Earth’s twin planet.

How did the University of Trento discover the lava tube on Venus?

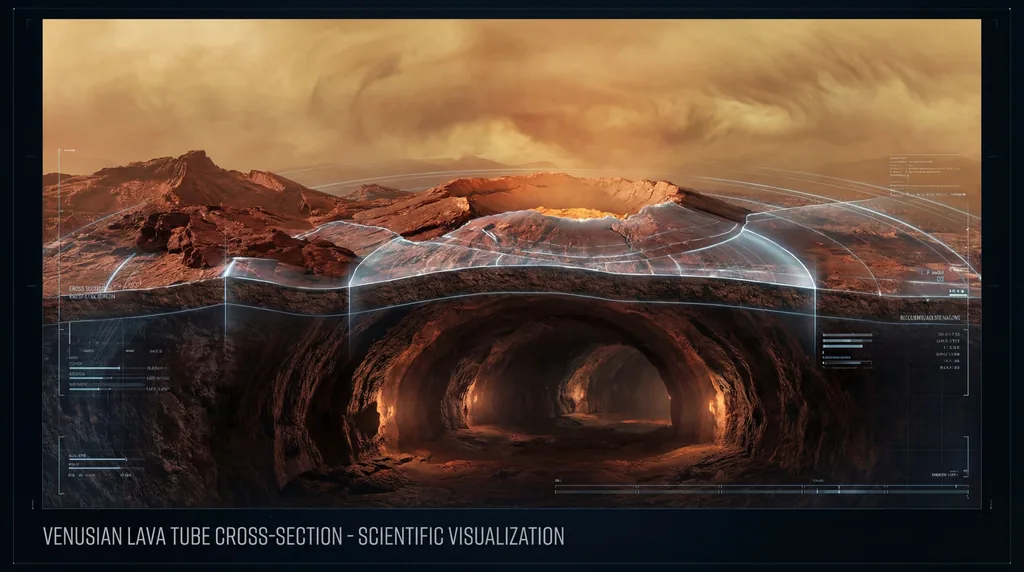

Researchers from the University of Trento discovered the lava tube on Venus by analyzing radar imagery from NASA's Magellan mission, focusing on the Nyx Mons region. They used innovative imaging techniques developed at the Remote Sensing Laboratory to examine localized surface collapses, or skylights, which revealed a subsurface conduit with a diameter of approximately one kilometer and a void depth of at least 375 meters.

Identifying these features on Venus is exceptionally difficult due to the planet’s thick, opaque atmosphere. Standard cameras cannot penetrate the dense sulfuric acid clouds, forcing scientists to rely on Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data collected between 1990 and 1992. By applying advanced signal processing to these legacy data sets, the team was able to distinguish between solid volcanic rock and the empty voids characteristic of a subsurface pyroduct.

The study focused on specific "skylights"—areas where the roof of an underground cave has collapsed due to geological stress or cooling. "The identification of a volcanic cavity is of particular importance, as it allows us to validate theories that for many years have only hypothesized their existence," explains Lorenzo Bruzzone, head of the Remote Sensing Laboratory at the University of Trento. This methodological breakthrough allows scientists to peer beneath the Venusian crust for the first time.

How do Venus lava tubes compare to those on Earth or the Moon?

Venus lava tubes are significantly larger than those on Earth, with diameters reaching one kilometer and potential lengths of at least 45 kilometers. These structures exceed the dimensions of terrestrial and Martian tubes and align with the upper limits of those found on the Moon, likely due to the specific atmospheric pressure and lower gravity found on Venus.

The formation of such massive conduits is driven by the unique environmental parameters of the planet. Key factors influencing their scale include:

- Lower Gravity: Relative to Earth, lower gravity allows for the formation of wider subterranean arches without structural collapse.

- Atmospheric Density: The dense Venusian atmosphere promotes the rapid creation of a thick insulating crust over active lava flows, facilitating the development of deep tubes.

- Lava Viscosity: The morphology of the Nyx Mons region suggests high-volume flows that create larger and longer channels than those typically observed on other rocky planets.

Geological modeling suggests that the discovered tube has a roof thickness of at least 150 meters. This robust structure has allowed the cavity to remain stable despite the extreme surface temperatures and pressures that characterize the Venusian environment. The presence of multiple similar pits in the surrounding terrain suggests that these subsurface conduits may form extensive networks across the volcanic plains.

Why is the discovery of a Venus lava tube important for future missions?

The discovery is important for future missions because lava tubes could serve as natural shelters from the planet's hostile surface and provide critical data on volcanic history. It validates the need for advanced radar systems on upcoming spacecraft, such as ESA’s EnVision and NASA’s VERITAS, which are designed to probe the planet's interior and atmospheric evolution.

Future exploration will rely heavily on specialized instrumentation to map these voids in greater detail. The EnVision mission, for instance, will carry a Subsurface Radar Sounder (SRS). This tool will be capable of probing several hundred meters beneath the surface, potentially detecting conduits even in areas where no surface skylights or collapses are visible. These findings will guide mission planners in selecting high-priority targets for orbital observation.

Furthermore, these tubes offer a "time capsule" of Venusian history. Because the interiors are shielded from the corrosive surface atmosphere, they may preserve geochemical evidence of the planet's past climate and volcanic activity. Bruzzone notes that this discovery represents "only the beginning of a long and fascinating research activity" that will redefine our search for active volcanism on Venus.

The implications for planetary science are profound, as the existence of these tubes suggests that Venus may have been geologically active more recently than previously thought. As scientists prepare for the next decade of Venusian exploration, the University of Trento's findings provide a roadmap for investigating the hidden depths of the solar system's most mysterious planet. Future robotic sensors might one day utilize these stable environments to survive the planet's 460-degree Celsius surface temperatures.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!