Earth’s magnetic whispers: stunning audio from space

On 22 January 2025, a paper in Nature reported a surprising find: spacecraft recorded intense, rising-frequency radio emissions — the kind that translate into birdlike "chirps" when sonified — at distances three times farther from Earth than expected. Scientists have begun calling these recordings, in both scientific papers and public briefings, earth’s magnetic whispers: stunning captures of plasma dynamics that until now were thought to be confined much closer to the planet. The signals were identified in data from NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission and analysed by an international team led from Beihang University; the discovery pushes the known habitat of these waves out into the stretched, near-tail region of Earth’s magnetosphere.

earth’s magnetic whispers: stunning chorus far from Earth

The recorded phenomena are a class of whistler‑mode plasma waves known as chorus. In sonic form they resemble birdsong because discrete elements of the emission sweep upward in frequency over fractions of a second; in physics terms those are narrowband electromagnetic bursts whose central frequency changes rapidly with time. Chorus waves had been routinely observed inside and near Earth’s radiation belts by earlier missions such as the Van Allen Probes; the new Nature study shows continuous chorus signatures appearing roughly 100,000 kilometres (about 62,000 miles) from Earth — well into the magnetotail where the planet’s field lines are highly stretched by the solar wind. That relocation matters because the magnetotail’s geometry and low background magnetic field change how particles and waves interact, forcing a rethink of both where chorus can form and how they gain the energy to chirp.

What generates these radio 'songs'?

Chorus and other magnetospheric radio emissions arise from interactions between populations of charged particles (electrons, primarily) and the geometry of Earth’s magnetic field. When a pocket of energetic electrons encounters a region of colder background plasma, nonlinear wave–particle interactions can amplify electromagnetic fluctuations into organised emissions. In a familiar picture, injections of electrons toward the night side — often triggered by magnetic reconnection or solar wind disturbances — set up the resonant conditions that let small perturbations grow into chorus. Those waves propagate along magnetic field lines in the whistler mode, a term that comes from their falling or rising pitches when converted to audio by shifting frequencies into the human hearing range.

Different voices of the magnetosphere

Space physicists distinguish among several named families of magnetospheric emissions. Whistler‑mode chorus is the rising‑tone, discrete chirp; plasmaspheric hiss is a broadband, hiss‑like static that fills the inner plasmasphere; and the classic "whistler" is the falling‑tone sound produced when lightning‑generated pulses propagate along field lines and disperse. All are radio emissions in the very low frequency (VLF) band or nearby, and all are measured as changing electric and magnetic fields by spaceborne sensors. Converting those signals into audible sound is a translation trick — researchers shift the recorded frequencies up to the audio band so humans can perceive the structure — but the physical waves themselves remain electromagnetic oscillations in plasma, not sound in air.

earth’s magnetic whispers: stunning recordings and how they’re made

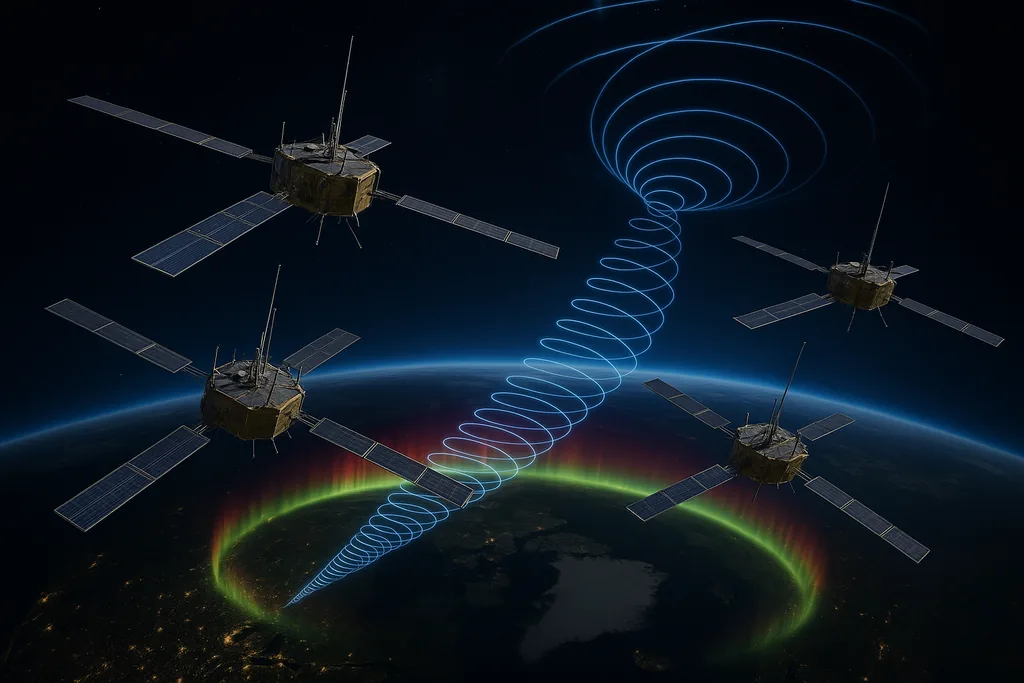

Satellites detect magnetospheric radio emissions with electric and magnetic field antennas and wideband receivers that record waveform snapshots and spectral power. Missions like MMS (four spacecraft flying in a tightly controlled formation), Van Allen Probes (a two‑satellite mission that operated through the 2010s), NASA’s Polar and earlier explorers, and ESA’s Swarm constellation all carry instruments designed to sample plasma and fields across frequency ranges that include whistler‑mode emissions. Analysts then produce frequency–time spectrograms showing where and when emissions occur; for public outreach, teams sometimes sonify those spectrograms so the rising or falling tones become audible. Such sonifications — including an ESA/Technical University of Denmark project that used Swarm data to create a public soundscape of Earth’s magnetic field — have helped convey the strangeness and immediacy of these invisible processes.

Why the new detection is surprising scientifically

The surprise built into the Nature result is twofold. First, chorus emissions had been expected to require the near‑dipolar field geometry and plasma conditions found relatively close to Earth; detecting continuous chorus elements deep in the magnetotail shows the waves can form in a much weaker, topologically different field. Second, the study presents observational evidence for nonlinear features — including phase‑space structures sometimes described as "electron holes" — that point to particular wave‑growth mechanisms. Those observations strengthen a nonlinear picture of chorus generation and demand that models of radiation belt dynamics and space weather account for a wider spatial range of wave activity. This is an active research area precisely because chorus can accelerate electrons to high energies and shape the Van Allen belts.

earth’s magnetic whispers: stunning implications for satellites and GPS

Plasma waves like chorus are not just curiosities for physicists; they are central actors in space weather. Through resonant interactions, whistler‑mode waves can energise electrons to relativistic speeds or scatter them into loss cones that precipitate into the atmosphere. That process can create so‑called "killer electrons" that damage satellite electronics, degrade solar panels and complicate mission operations. More subtly, strong wave activity can change local plasma densities and field fluctuations that perturb radio propagation, with knock‑on effects for precise navigation signals such as GPS. The new finding — that chorus can appear far from Earth in regions previously thought quieter — implies more places where spacecraft may encounter wave‑driven hazards and where space‑weather forecasting models will need to be revised.

How scientists will follow this trail

Researchers now want to see whether the detected events are rare or part of a larger, previously unrecognised population. That requires combing archival MMS waveforms, coordinating observations with other assets (for example, upstream solar wind monitors and low‑altitude auroral imagers), and running targeted simulations of wave–particle dynamics in magnetotail geometries. The Nature paper’s authors and accompanying commentaries have already called for more multi‑mission campaigns to map where chorus forms and how it couples to electrons across the magnetosphere. Better mapping will directly feed efforts to improve radiation‑belt models and operational warnings for satellite operators.

The human angle: making the invisible audible

Beyond technical stakes, the sonified recordings — whether the MMS chorus clips or the Swarm‑based "scary sound of Earth's magnetic field" — make an invisible, global process tangible to the public. Those audio renditions are educational tools: they help non‑specialists grasp that Earth is embedded in a dynamic plasma environment that sings, hisses and whistles depending on solar forcing and internal magnetospheric dynamics. The poetic label earth’s magnetic whispers: stunning captures that dual reality — rigorous, quantitative science and an aesthetic encounter with planetary processes.

What scientists still don’t know

Key uncertainties remain about the precise sources of free energy that drive chorus so far down the tail, how common the deep‑tail chorus events are, and the role that large‑scale drivers (such as interplanetary shocks and coronal mass ejections) play in seeding or amplifying them. Resolving those questions will require both fresh observations and refined theory; the MMS dataset, with its high‑time‑resolution fields and particles, provides fertile ground. In the meantime, satellite operators and mission designers should take note: the magnetosphere’s soundtrack is richer, and potentially riskier, than previously assumed.

Sources

- Nature (Liu et al., "Field–particle energy transfer during chorus emissions in space", published 22 January 2025)

- NASA — Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission / Goddard Space Flight Center (explainers on whistler‑mode waves and chorus)

- European Space Agency — Swarm mission (data used in sonification projects and core‑field studies)

- University of Iowa / Van Allen Probes (EMFISIS instrument descriptions and past chorus observations)

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!