How do quasars help map dark matter?

Quasars help map dark matter by acting as luminous tracers that reside within massive invisible halos, revealing the underlying gravitational structure of the universe. Because these supermassive black holes congregate in regions of high density, their spatial clustering allows astronomers to infer the distribution of dark matter across billions of light-years, even though the matter itself emits no light.

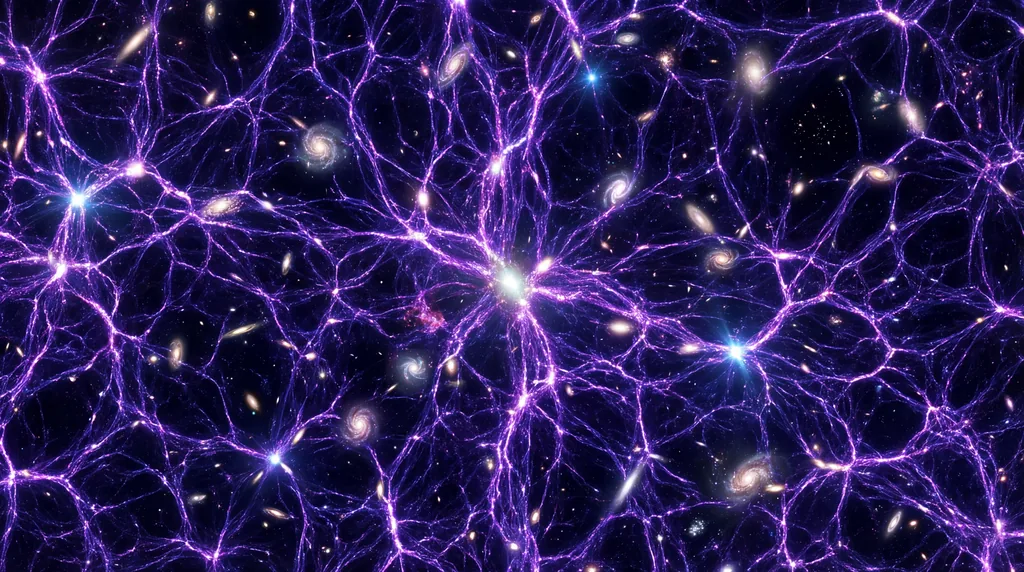

The Large-Scale Structure of the Universe is often described as a "cosmic web," a complex network of filaments and nodes where matter concentrates. Mapping this web is a monumental task because the vast majority of its mass consists of dark matter, which does not interact with electromagnetic radiation. To overcome this, researchers Guilhem Lavaux, Jens Jasche, and Arthur Loureiro utilized the recently released Quaia Quasar Catalogue. By treating quasars as "cosmological beacons," the team was able to reconstruct the three-dimensional "skeleton" of the universe across a record-breaking expanse of 10 billion light-years.

Quasars are particularly useful for this type of reconstruction because of their extreme luminosity, which allows them to be seen across vast "redshift" ranges. This study leveraged the Gaia spacecraft’s data to create two primary samples: the "Clean" sample (G < 20.0) and the "Deep" sample (G < 20.5). These samples provide a broad, all-sky coverage that is essential for understanding how matter has clustered over cosmic time. By analyzing the "quasar bias"—the mathematical relationship between where quasars appear and where the highest concentrations of matter reside—the researchers could visualize the invisible scaffolding of the cosmos with unprecedented scale.

How does the Gaia mission contribute to cosmology?

The Gaia mission contributes to cosmology by providing precise astrometric data for billions of celestial objects, enabling the creation of detailed 3D maps of the universe. While originally designed to map the Milky Way, Gaia’s all-sky survey capabilities now allow cosmologists to link local galactic structures to the Large-Scale Structure of the Universe and test fundamental theories of physics.

While Gaia is primarily known for its revolutionary impact on galactic archaeology, its ability to identify and categorize millions of quasars has opened new doors for field-level cosmology. The Quaia catalogue, derived from Gaia's broad optical-band magnitude data, offers a unique advantage: it provides a consistent, all-sky view that ground-based telescopes often struggle to match due to atmospheric interference and limited field-of-view. This comprehensive coverage is vital for field-level inference, a method that reconstructs the entire density field rather than just calculating average statistics.

To process this massive dataset, the research team employed the BORG (Bayesian Origin Reconstruction from Galaxies) algorithm. This sophisticated framework uses a physics-based "forward model" to simulate how the universe evolved. The methodology incorporates several critical factors:

- Lagrangian Perturbation Theory: A mathematical framework used to model the movement of matter from the early universe to the present day.

- Light-cone Effects: Adjustments that account for the fact that we see distant objects as they were in the past, not as they are today.

- Redshift-space Distortions: Corrections for the apparent displacement of objects caused by their peculiar velocities toward or away from us.

- Survey Selection Effects: Accounting for "sky cuts" and foreground contamination to ensure the data is representative of the true cosmic distribution.

What did the universe look like at the time of the Big Bang?

At the time of the Big Bang, the universe was an incredibly hot, dense, and nearly uniform plasma where matter and energy were indistinguishable. Microscopic quantum fluctuations in this primordial state served as the "seeds" for all future structures, eventually collapsing under gravity to form the dark matter halos and galaxies observed in the modern cosmic web.

One of the most profound achievements of the BORG algorithm is its ability to perform "reverse-engineering" on a cosmic scale. By applying this algorithm to the Quaia catalogue, Lavaux, Jasche, and Loureiro were able to reconstruct the initial conditions of the universe—essentially creating a map of what the cosmos looked like shortly after the Big Bang. This process involves tracing the trajectories of particles backward through time, accounting for the expansion of space and the gravitational pull of evolving structures.

The resulting reconstructions span a comoving volume of (10h⁻¹ Gpc)³ with a spatial resolution of 39.1 h⁻¹Mpc. This represents the largest field-level reconstruction of the observable universe to date. By bridging the gap between the primordial seeds of the early universe and the present-day distribution of dark matter, the study provides a continuous narrative of cosmic evolution. The researchers validated these maps through cross-correlation with Planck CMB lensing data, detecting a signal at approximately 4σ significance, which confirms that their 3D models accurately reflect the real distribution of mass in the universe.

The Significance of Field-Level Inference

Field-level inference represents a shift in how we study the cosmos. Traditional methods often rely on two-point correlation functions, which look at the average distance between pairs of galaxies. However, field-level inference, as used in this study, attempts to reconstruct the specific density at every point in space. This provides a high-fidelity data product, including posterior maps of initial conditions, present-day dark matter density, and velocity fields. These maps allow scientists to see not just the average properties of the universe, but the specific "web" that connects galaxies together across 10 billion light-years.

Future Implications and Dark Energy

The implications of this 3D map extend far beyond mere visualization; they provide a new tool for probing the mysteries of dark energy. By understanding the precise growth of cosmic structures over the last 10 billion years, scientists can better measure how dark energy has accelerated the expansion of the universe. The framework established in this work is designed to be scalable, meaning it can be applied to future wide-field surveys from upcoming missions like Euclid or the Vera C. Rubin Observatory.

In summary, the use of the Quaia Quasar Catalogue and the BORG algorithm has transformed our ability to see the invisible. By tracing the paths of the most distant beacons in the sky, researchers have mapped the dark matter skeleton of our universe, providing a window into the past that stretches back to the very dawn of time. This work not only delivers a high-resolution map of the present-day cosmos but also establishes a robust methodology for all future attempts to decode the history of the Big Bang and the evolution of the large-scale structure.