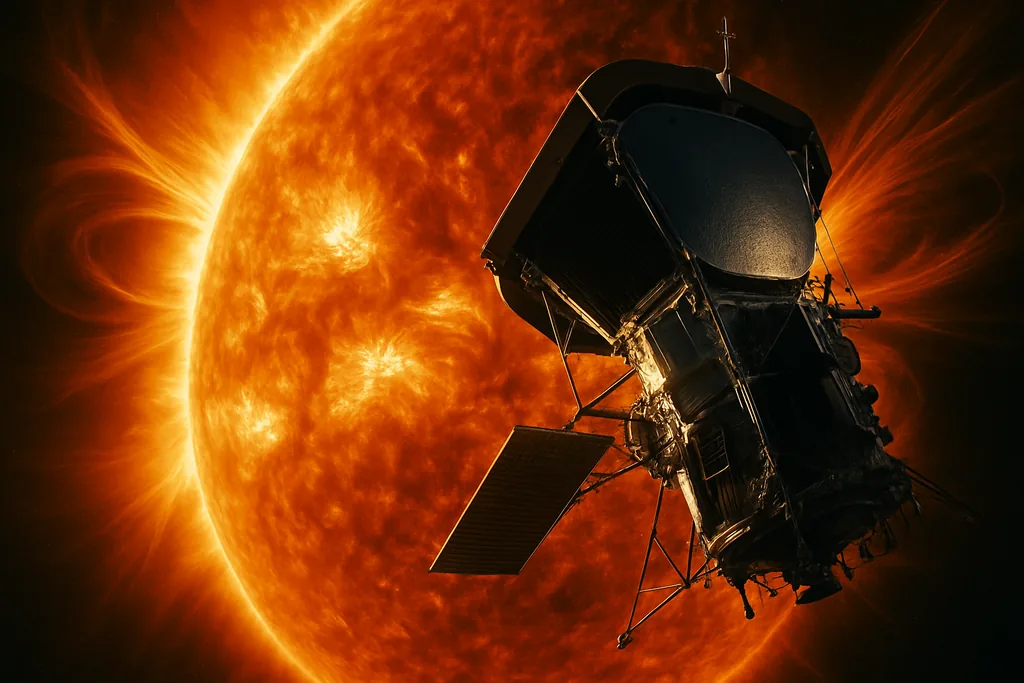

Near enough to feel the Sun's breath: a spacecraft flew closer sun than ever

Early this year, a spacecraft flew closer sun than any other explorer in history and returned a set of measurements that are forcing physicists to rewrite a classic problem in solar science. NASA's Parker Solar Probe has repeatedly dipped deep into the Sun's outer atmosphere, coming as near as about 3.8 million miles from the visible solar surface during its most daring encounters. Those raw, in‑situ particle and field readings — taken where the solar wind is born and still interacts strongly with the Sun's magnetic field — are now being used with new analysis tools to expose how energy is transferred into the wind and why the corona sits at millions of degrees.

Parker Solar Probe launched in 2018 and uses a sequence of Venus gravity assists to lower its perihelion into the inner heliosphere. On its closest passages the spacecraft has crossed into regions that were, until recently, purely theoretical territory for heliophysicists. That proximity matters: instruments aboard the probe sample the velocity distributions of ions and electrons directly, not indirectly through remote light or radio signatures. Those distributions do not look like the simple, bell‑shaped Maxwellian curves that many models assume; instead they are skewed and structured, carrying fingerprints of recent heating and wave activity.

Because the probe physically traverses the corona and the young solar wind, scientists can compare local measurements against the expectations of long‑standing theories. The data set is unusual in both its proximity and fidelity: magnetic fields, particle speeds and densities, electromagnetic waves across a range of frequencies — all measured within a few million miles of the Sun. That combination is what lets researchers test, reject and refine heating mechanisms that have been debated for more than a century.

Why the spacecraft flew closer sun reveals coronal heating clues

The century‑old mystery at the heart of these observations is the coronal heating problem: the Sun's outer atmosphere, the corona, is orders of magnitude hotter than the visible surface below it. The photosphere sits near 5,800 kelvin, but the corona reaches temperatures of millions of kelvin. How energy moves from the lower layers of the Sun up into a tenuous plasma that nevertheless becomes far hotter has been a puzzle since high coronal temperatures were first inferred in the early 20th century.

New work published this year uses Parker's close measurements together with a numerical analysis tool called ALPS — the Arbitrary Linear Plasma Solver — to confront that puzzle directly. ALPS lets scientists compute how observed, non‑Maxwellian particle velocity distributions interact with ion‑scale electromagnetic waves: which waves are emitted, which are absorbed, and how much energy is exchanged. The result is a far more detailed accounting of energy flow in the inner heliosphere than earlier models that assumed thermalised particle populations.

What the probe found: waves, damping and slow cooling

The headline from the new analysis is that the solar wind does not simply expand and cool as it escapes the Sun; rather, it experiences ongoing heating from small‑scale wave–particle interactions. Parker's measurements show persistent anisotropies and departures from thermal equilibrium in ion speeds, and ALPS indicates that these non‑thermal features enable the emission and absorption of ion‑scale waves. Absorption of these waves by specific particle populations transfers energy to particles and slows the cooling that would otherwise result from pure expansion.

Scientists describe the observable consequence as 'damping': wave energy is converted into particle kinetic energy and redistributed among ions and electrons. That damping is not uniform — it depends on local magnetic geometry, the shape of the velocity distributions, and which wave modes are present — and this spatially varying heating helps explain why the corona stays so hot close to the Sun and how the solar wind gains its speed as it streams outward.

Impacts for space weather, satellites and astrophysics

These are not just esoteric details. Better understanding of how and where the solar wind is heated feeds directly into models that forecast how coronal mass ejections and particle storms evolve on their way to Earth. A more realistic treatment of particle distributions and damping will change calculations of how fast and how energetic solar eruptions become as they travel through the heliosphere. For operators of satellites, power grids and aviation routes near the poles, that can translate into improved warnings and reduced risk.

Beyond the near‑Earth environment, the physics uncovered where a spacecraft flew closer sun than ever has broad reach. Hot, magnetised plasmas are ubiquitous across the universe — in accretion disks around black holes, winds from other stars, and the tenuous gas between galaxies. The same kinds of wave–particle processes and non‑thermal velocity distributions likely control energy dissipation in those systems too, so lessons from Parker will be folded into astrophysical models for years to come.

How this changes the picture and what comes next

Until now, many models treated the nascent solar wind as approximately thermal and used simplified prescriptions for wave heating. The new, direct measurements show those assumptions miss important channels of energy transfer. By combining in‑situ data with solvers like ALPS, researchers can now predict which particle populations gain energy and at what radial distances — predictions that can be validated against Parker's repeated passes as the spacecraft samples different parts of the corona through the solar cycle.

Next steps include expanding the set of encounters analysed, comparing Parker's data with remote observations from other spacecraft, and incorporating the refined heating terms into global heliospheric models. Teams are already working to map the 'point of no return' in the Sun's atmosphere — the boundary where plasma escapes the magnetic containment of the Sun — and to chart how damping and wave absorption change with solar activity. As Parker continues to lower its perihelion, those maps will gain resolution and predictive power.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!