Researchers using neural-network-based quantum Monte Carlo simulations have discovered a novel state of quantum matter known as a paired Wigner crystal within the landscape of artificial graphene. This discovery reveals that at a specific density, electrons spontaneously form singlet-like valence bonds that aggregate into a molecular crystal, a phenomenon that challenges existing models of electron repulsion. By leveraging artificial intelligence to solve complex many-body equations, the study led by researchers Yixiao Chen, Zhou-Quan Wan, and Conor Smith provides a new framework for understanding how collective quantum behaviors emerge in moiré superlattices.

What is a paired Wigner crystal?

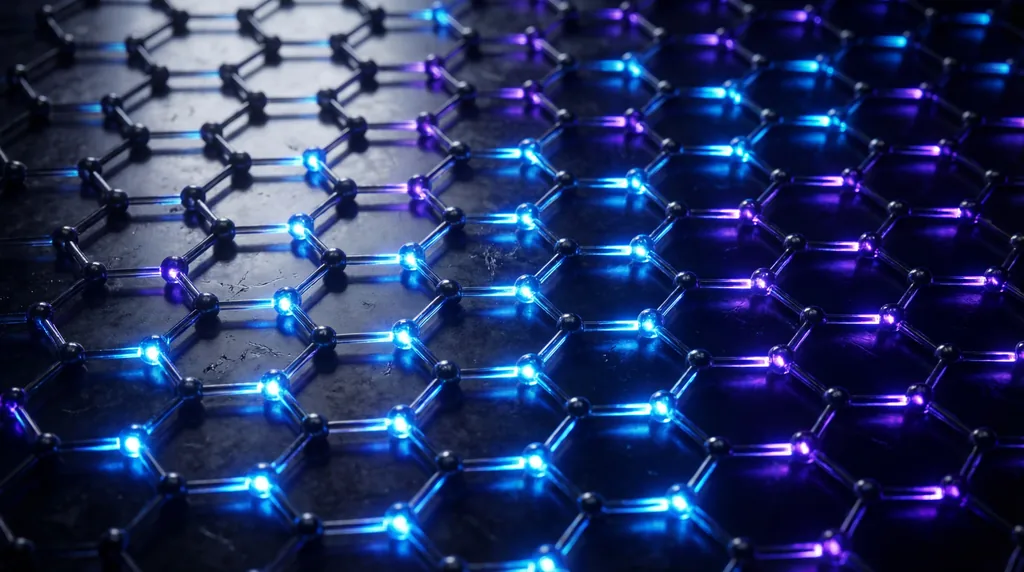

A paired Wigner crystal is an exotic quantum state where opposite-spin electrons bind into singlet-like valence bonds across hexagonal moiré minima, eventually forming a triangular molecular lattice. This state is unique because it restores local C6 symmetry within hexagonal molecules, occurring at low filling factors without the need for external confining potentials or attractive forces that typically facilitate particle pairing.

Traditional Wigner crystals are formed when the electrostatic repulsion between electrons becomes so dominant that the particles "freeze" into a rigid, crystalline lattice to minimize energy. However, in this newly discovered paired state, the electrons do not remain isolated. Instead, they exhibit a collective "pairing" behavior that was previously considered unlikely in systems dominated by purely repulsive Coulomb interactions. This pairing creates a "molecular" structure where the electron density is distributed across multiple sites within the moiré potential.

The discovery identifies that these molecules of pairs subsequently arrange themselves into a molecular Wigner crystal. This transition occurs at a specific filling factor of νm = 1/4, meaning there is one electron for every four moiré minima. Key characteristics of this state include:

- Singlet-like valence bonds: Two electrons with opposite spins pair up despite their mutual repulsion.

- Symmetry restoration: The formation of these pairs restores the hexagonal symmetry of the local lattice environment.

- Depleted minima: The crystallization process leaves approximately one-quarter of the moiré potential wells mostly empty.

What is artificial graphene?

Artificial graphene refers to engineered quantum systems, such as moiré superlattices, that simulate the electronic properties of natural graphene through a tunable periodic potential. These systems are created by stacking layers of two-dimensional materials with a slight twist or lattice mismatch, allowing scientists to observe exotic quantum states that are difficult to access in naturally occurring crystals.

In modern condensed matter physics, artificial graphene serves as a highly versatile laboratory for "engineering" quantum matter. Unlike natural graphene, where the atomic structure is fixed, the properties of moiré systems can be adjusted by changing the twist angle between layers or applying external electric fields. This tunability allows researchers to control the kinetic energy of electrons relative to their interaction energy, making it an ideal platform for studying strongly correlated physics.

The research conducted by Chen, Wan, and Smith utilized a honeycomb moiré potential to mimic the hexagonal structure of graphene. In this environment, the two-dimensional electron gas behaves in ways that defy classical intuition. By simulating these conditions, the team was able to observe how electrons navigate the "landscape" of the potential wells, leading to the identification of the paired Wigner crystal—a state that might remain hidden in less flexible material structures.

Neural Networks and Quantum Monte Carlo Methodology

The complexity of simulating quantum many-body systems stems from the Schrödinger equation, which becomes exponentially difficult to solve as the number of interacting particles increases. To overcome this, the research team employed a neural-network-based quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) approach. This method uses artificial neural networks as a "variational ansatz," essentially a highly sophisticated mathematical guess, to represent the many-body wave function of the electrons.

Traditional QMC methods often struggle with the "sign problem" in fermionic systems, which can lead to inaccuracies when calculating the ground states of electrons. However, neural networks are exceptionally efficient at identifying patterns within high-dimensional data, allowing the simulation to "learn" the most stable energy configuration. This AI-driven methodology allowed the researchers to scan for unknown ground states that traditional theoretical frameworks might have overlooked due to the strong interactions involved.

By utilizing these advanced computational tools, the scientists were able to simulate the honeycomb moiré potential with high precision. The neural network identified that at a filling factor of 1/4, the system naturally lowered its energy by forming the paired molecular state. This demonstrates a significant shift in computational physics, where machine learning is no longer just a tool for data analysis but a primary engine for scientific discovery in quantum mechanics.

Why is the paired Wigner crystal significant in quantum matter?

The paired Wigner crystal is significant because it represents a previously unknown phase of matter that emerges solely from collective electron interactions without external assistance. This discovery expands the known catalog of moiré phases and proves that neural-network computational methods can reveal complex quantum phenomena that elude standard theoretical predictions and experimental observations.

The significance of this finding lies in the "spontaneous" nature of the pairing. Usually, for electrons to pair up (a prerequisite for phenomena like superconductivity), there must be an attractive force, such as lattice vibrations (phonons). In the artificial graphene model studied here, there is no such attractive interaction. The pairing is an emergent property of the strongly interacting quantum many-body system, suggesting that our understanding of electron correlation is still evolving.

Furthermore, the discovery of a molecular crystal at the νm = 1/4 filling factor provides a roadmap for future material design. Understanding how these states form could lead to the development of materials with "exotic" properties, such as:

- Non-trivial topological insulators: Materials that conduct electricity on their surface but act as insulators in their bulk.

- Paired supersolids: Hypothetical states of matter that exhibit both crystalline structure and frictionless flow.

- Enhanced Superconductivity: Insights into electron pairing could unlock higher-temperature superconducting materials.

Future Implications for Quantum Materials

The identification of the paired Wigner crystal in artificial graphene marks a milestone in the field of condensed matter physics. It validates the use of moiré systems as a "quantum simulator" capable of mimicking high-energy physics in a solid-state device. For researchers like Yixiao Chen and colleagues, this is likely only the beginning of a broader exploration into how electron density and potential geometry influence quantum topology.

Looking forward, the integration of AI and machine learning into the discovery of quantum materials is expected to accelerate. As neural networks become more adept at simulating complex particle interactions, they will enable the "pre-discovery" of materials in a virtual environment before they are ever synthesized in a lab. This could drastically reduce the time and cost associated with developing quantum computing components and high-efficiency electronic devices.

Ultimately, this research suggests that the "zoo" of quantum states is much larger than previously thought. The fact that artificial graphene can host such a diverse array of phenomena—ranging from Mott insulators to this new paired Wigner crystal—confirms that we are entering a new era of material science where we can manipulate the very fabric of quantum behavior to suit our technological needs.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!