A week of strange particles, in flat and hidden landscapes

This week the phrase particles detected another dimension moved from science‑fiction headlines into the language of working physicists — but it needs unpacking. Two teams have published work showing that quasiparticles with exchange properties unlike ordinary bosons or fermions can be created, controlled and observed in systems that are effectively lower dimensional, while a separate theoretical proposal argues that entirely different particle properties — including masses — might emerge from hidden higher‑dimensional geometry. Taken together, these developments revive an old question with sharper tools: what does it mean to detect particles in another dimension, and how closely do laboratory flatlands or mathematical extra dimensions map onto the three‑dimensional universe we inhabit?

particles detected another dimension: one-dimensional anyons mapped

The clearest experimental story comes from researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and collaborators at the University of Oklahoma, whose papers in Physical Review A describe how anyons — quasiparticles that interpolate between bosons and fermions — can appear in systems constrained to one spatial dimension and, crucially, how their exchange statistics can be tuned. Anyons were first predicted in the 1970s and observed as emergent excitations in two‑dimensional systems (notably in fractional quantum Hall devices) only in the last decade. The new work shows that when atoms or quasiparticles are forced into one‑dimensional motion, the mathematical factor that records what happens when two identical particles swap places need not be limited to +1 or −1; it becomes a continuous, experimentally accessible parameter linked to short‑range interactions.

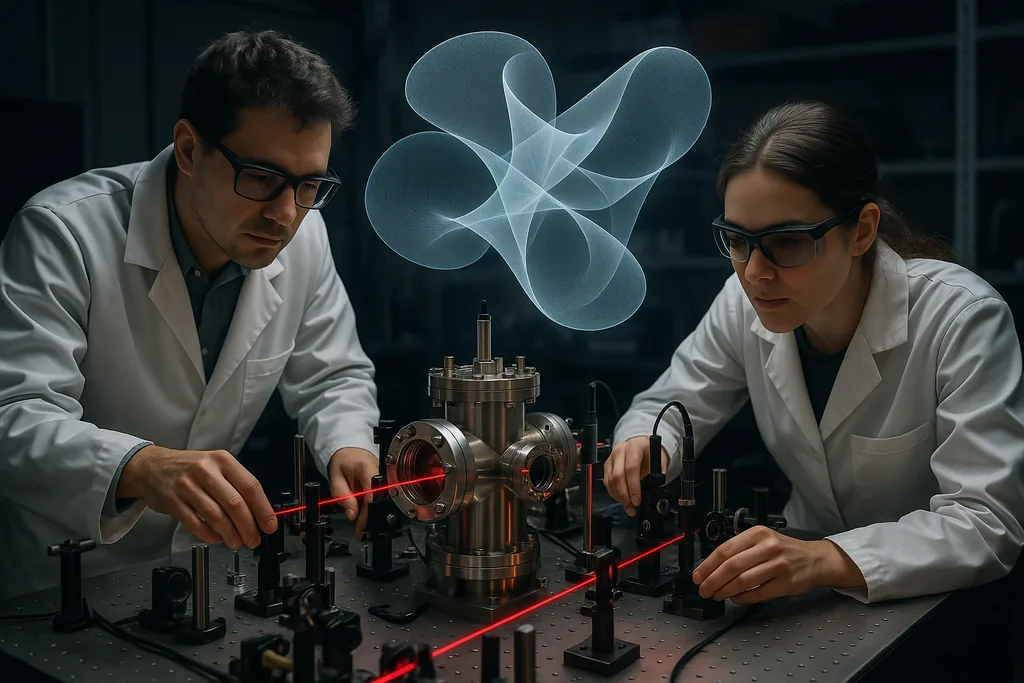

That matters because in laboratory settings — ultracold atoms in optical lattices, tailored semiconducting heterostructures or strongly confined channels — researchers can now design and measure momentum distributions and scattering signatures associated with these one‑dimensional anyons. In practical terms, physicists have a recipe to generate and adjust an exchange factor, so the claim isn’t that a brand‑new elementary particle popped out of nowhere, but that collective excitations in engineered, effectively lower‑dimensional systems behave like a third kind of particle when you look at their exchange statistics. The papers provide the theoretical mapping and point to concrete experiments that are already feasible with existing cold‑atom toolkits.

particles detected another dimension: geometry and mass in seven hidden dimensions

That proposal is bolder: it suggests the foundations of the Standard Model might be reformulated so that some particle properties are emergent features of higher‑dimensional geometry rather than the action of a separate scalar field. The idea links geometry, spontaneous symmetry breaking and cosmological observables, and it would have profound implications for how physicists connect particle physics and gravity. But it’s a theoretical claim that requires experimental support beyond mathematical plausibility; the community will expect new, testable predictions before treating it as a replacement for the well‑tested Higgs mechanism.

How experimental teams search for extra‑dimensional signatures

When journalists say "particles detected another dimension" they often mean two distinct things: quasiparticles confined to fewer dimensions inside a lab, and hypothetical particles tied to hidden extra dimensions of spacetime. The experimental strategies for the two are fundamentally different. In the lab, cold‑atom experiments and atomically thin semiconductors create effective two‑ or one‑dimensional environments where motion out of plane is suppressed. Researchers then look for telltale signatures — altered momentum distributions, fractionalised charge, or braiding‑style memory effects in interferometry — that indicate anyonic exchange statistics. Those are direct, controlled tests that can be repeated and refined.

What 'detection in another dimension' would change about physics

Could the discovery of particles tied to dimensions beyond our everyday three rewrite the foundations of physics? The short answer: it depends what is discovered. Demonstrating controllable anyons in 1D or 2D is already a major shift for condensed‑matter and quantum information physics: anyons provide alternative ways to store and process quantum information that are intrinsically protected by topology, and they expand the taxonomy of emergent excitations. Those findings do not, however, overturn the Standard Model because anyons are quasiparticles — emergent, collective modes that appear inside materials rather than new elementary fields in the vacuum.

Credible theories, caveats and the role of idealisation

The physics community has long had credible frameworks that predict dimension‑dependent particles. Anyons arise cleanly from the topology of configuration space in reduced dimensionality and have experimental precedence in two‑dimensional quantum Hall systems. The new one‑dimensional results expand those ideas and show how tunability can be achieved. Hidden‑dimension proposals — including G2‑manifold constructions — belong to a different lineage that stretches from Kaluza–Klein ideas to string theory and modern geometric approaches. These are mathematically rich and physically motivated, but they are also model‑dependent and face the strict test of empirical evidence.

Philosophers and physicists alike warn about idealisation: two‑dimensional calculations can reveal possibilities that vanish once the real world’s third dimension is allowed, so laboratory confinement and robust experimental signatures are crucial. In short, an observed anyon in a flat lab is real for the system that produces it; a hidden‑dimension particle is only as real as the empirical signatures that survive careful scrutiny.

Where next: experiments, tests and the timeline

Either route is valuable. Bench experiments that pin down exotic exchange statistics will help quantum technologies and sharpen theoretical tools. Ambitious geometric proposals, if they survive theoretical and experimental pressure, could alter how we think about the origin of mass and the interface of quantum field theory and gravity. For now, the safest reading of the phrase particles detected another dimension is that physicists are detecting dimension‑dependent particle behaviour in engineered systems, and separately testing speculative but mathematically motivated ideas that link particles to hidden geometry.

The coming months and years will show whether these are incremental advances in condensed‑matter physics or the first hints of a deeper geometric rewrite of particle physics. Either outcome promises new experiments, refined theory and — most importantly — concrete, testable predictions.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!