Ultracold atoms reveal type: a sudden quantum switch

This week researchers published a striking finding that ultracold atoms reveal type of transition previously unseen in simple atom–molecule Bose‑Einstein condensates: an abrupt, first‑order phase jump driven by coherent three‑body recombination. In conventional experiments the balance between free atoms and Feshbach molecules shifts smoothly as experimenters tune the molecular energy, producing a continuous crossover. The new work shows that when a reversible three‑atom collision process becomes dominant it reshapes the free‑energy landscape into a double well, producing a discontinuous change in the condensate composition, controllable bistability, and molecular metastability.

Ultracold atoms reveal type: what the theory says and why it matters

That abruptness is not just a mathematical curiosity. In the double‑well regime the condensate can exhibit bistability — two locally stable macroscopic states for the same external control settings — and metastable molecular condensates that survive even where linear theory would predict decay. Quantum correlations are enhanced near the transition, and the authors identify atom–molecule entanglement that trends toward an atom–molecule “cat state”, a nonclassical superposition that could be harnessed as a resource for sensing or information tasks. The work argues that this mechanism gives experimentalists a new, powerful knob for state engineering in ultracold systems rather than only a passive diagnostic of phases.

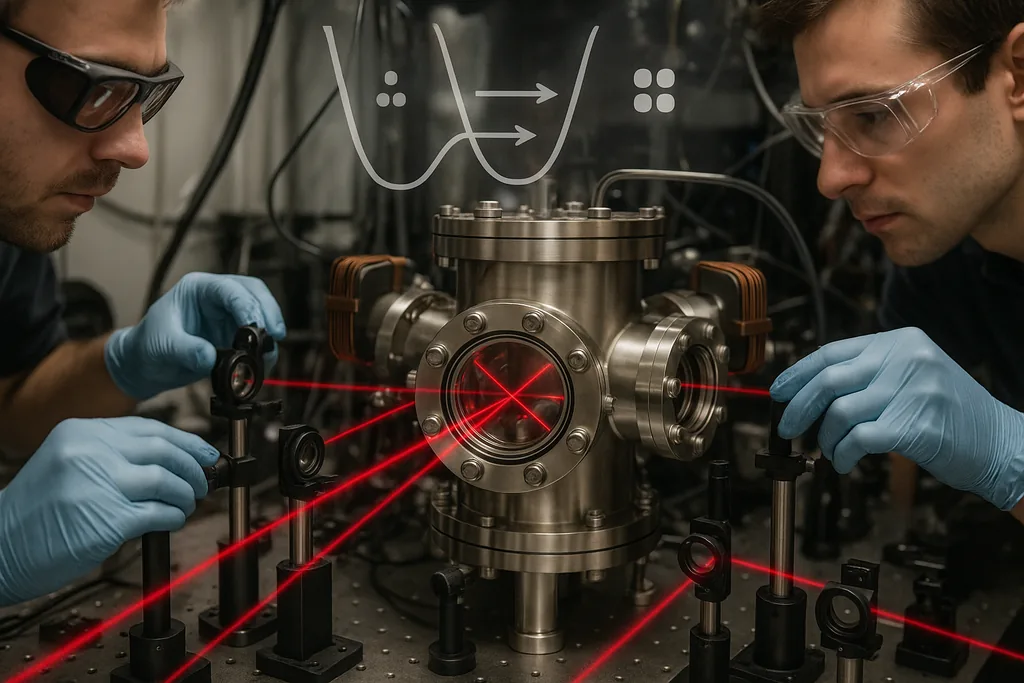

How experiments can tune the switch

Realising the new transition in the lab relies on controls already familiar to ultracold‑atom physicists, but used in a new parameter regime. A Fano–Feshbach resonance provides the usual handle on the molecular energy: an external magnetic field shifts the detuning and changes the two‑body coupling strength between atom pairs and a molecular bound state. The coherent three‑body recombination term, by contrast, becomes important at sufficiently high densities and when the collisional dynamics are slow and phase coherent. Careful control of density, magnetic detuning and collisional timescales can therefore move an experiment into the cTBR‑dominated regime where the double‑well appears.

To show the predicted bistability and metastability the theorists outline quench protocols in which detuning is rapidly changed across the transition and the subsequent dynamics are observed. Because the metastable molecular state can persist beyond the parameter boundary those quenches should reveal hysteresis and long‑lived molecular populations — clear experimental signatures. The calculations also show the phenomena are sensitive to the total atom number: as the system size grows certain avoided crossings narrow, which may limit tunnelling between wells and place practical constraints on scaling the effect to very large ensembles.

Protocols and tools: Raman control, spin‑orbit schemes and superradiant probes

While the first paper establishes the thermodynamics and phase diagram, other recent work points to experimental toolkits for implementing and probing the new switch. Separate studies on spin‑orbit coupled Bose‑Einstein condensates demonstrate how tailored Raman laser sequences and inverse‑engineering algorithms can simultaneously control internal pseudospin and motional degrees of freedom with high fidelity. Those protocols are robust against realistic imperfections and can be used to prepare precise initial states and drive controlled transitions — capabilities that complement the cTBR strategy by giving experimentalists better state‑preparation and readout techniques.

On the measurement side, teams working with dipolar gases have shown that Rayleigh superradiant light scattering can act as both a sensitive probe and an active control tool for phase transitions, for example between a condensate and a self‑bound quantum droplet. Superradiant scattering can deplete atoms in a controlled way and reveal changes in coherence and expansion dynamics; those same optical probes could be adapted to detect the sudden atom–molecule switch, map out hysteresis, and even nudge the system between minima of the double well. Combining magnetic tuning, Raman control and optical scattering therefore gives a practical experimental pathway to realise, register and manipulate the predicted first‑order transition.

What this transition changes for quantum control and sensing

An abrupt, controllable phase switch is appealing for quantum technologies because it behaves qualitatively differently from slow crossovers. First, discontinuous switching offers a fast, high‑contrast way to move the system between macroscopic states, useful for state preparation and for implementing digital‑style control elements inside analogue quantum simulators. Second, bistability provides a form of memory: once the system is steered into one well it can remain there without continuous control, potentially reducing overhead for some protocols.

Enhanced atom–molecule entanglement near the transition opens applications in quantum metrology where correlated states improve sensitivity. The metastable molecular condensates and the predicted hysteresis also point toward controlled ultracold chemistry experiments where reaction pathways are switched on or off by an external field. More speculative avenues include using the double‑well landscape as a platform to study macroscopic superpositions and decoherence, or to design new many‑body states for simulation of condensed‑matter models that rely on abrupt order‑parameter changes.

Practical limits and next steps

The promise of a new switch comes with clear experimental challenges. Coherent three‑body recombination must dominate without introducing destructive loss: in many systems three‑body collisions lead to heating and particle loss, so the window where cTBR is coherent and reversible could be narrow. Larger atom numbers tighten avoided crossings in the spectrum and can suppress the tunnelling that allows the system to explore both wells, complicating attempts to scale up the idea. Noise, uncontrolled inelastic processes and imperfect state preparation will also blur the sharpness of the switch in real setups.

Nevertheless, the field now has a practical roadmap. Immediate experimental efforts will combine magnetic detuning across Feshbach resonances, density control, Raman‑based state preparation and time‑resolved optical probes such as superradiant scattering. Demonstrating hysteresis or metastability in an existing cold‑atom apparatus would be a convincing first step; from there, adapting inverse‑engineering pulse sequences and exploring different geometries or species may widen the regime where the effect is robust. If successful, the new first‑order switch will become another tool in the ultracold toolbox for engineering nontrivial quantum states and controlled reaction dynamics.

For experimentalists and theorists alike the result reframes how we think about phase structure in minimal atom–molecule systems: a familiar smooth crossover can hide an abrupt switch when higher‑order coherent collisions are turned up. The interplay of adjustable interactions, coherent collisional channels and modern optical control sets the stage for experiments that do far more than observe quantum matter — they will actively reconfigure it on demand.

Sources

- ArXiv: First‑order phase transition in atom‑molecule quantum degenerate mixtures with coherent three‑body recombination (theoretical paper reporting the cTBR‑driven first‑order transition)

- ArXiv: Quantum state engineering of spin‑orbit coupled ultracold atoms in a Morse potential (protocols for Raman and inverse‑engineering control of Bose‑Einstein condensates)

- ArXiv: Unveiling the BEC‑droplet transition with Rayleigh superradiant scattering (experimental superradiant probe of condensate‑to‑droplet transitions)

- Shanghai University (spin‑orbit coupling and Raman control research)

- Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (superradiant scattering experiments)

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!