This week a multi‑institution team published protocols for what they call a many‑body phase microscope — a matter‑wave imaging scheme that lets experimenters directly measure the phases and long‑range coherences of quantum matter. The technique, set out in an ArXiv protocol by researchers including Christof Weitenberg (TU Dortmund), Luca Asteria (Kyoto University) and a team around Fabian Grusdt (Ludwig‑Maximilians‑Universität München), promises to overcome a long‑standing blind spot of quantum gas microscopes: access to phase information and off‑diagonal correlators. In short: this microscope reveals hidden quantum structure that density or spin snapshots alone cannot show.

How the microscope reveals hidden quantum order

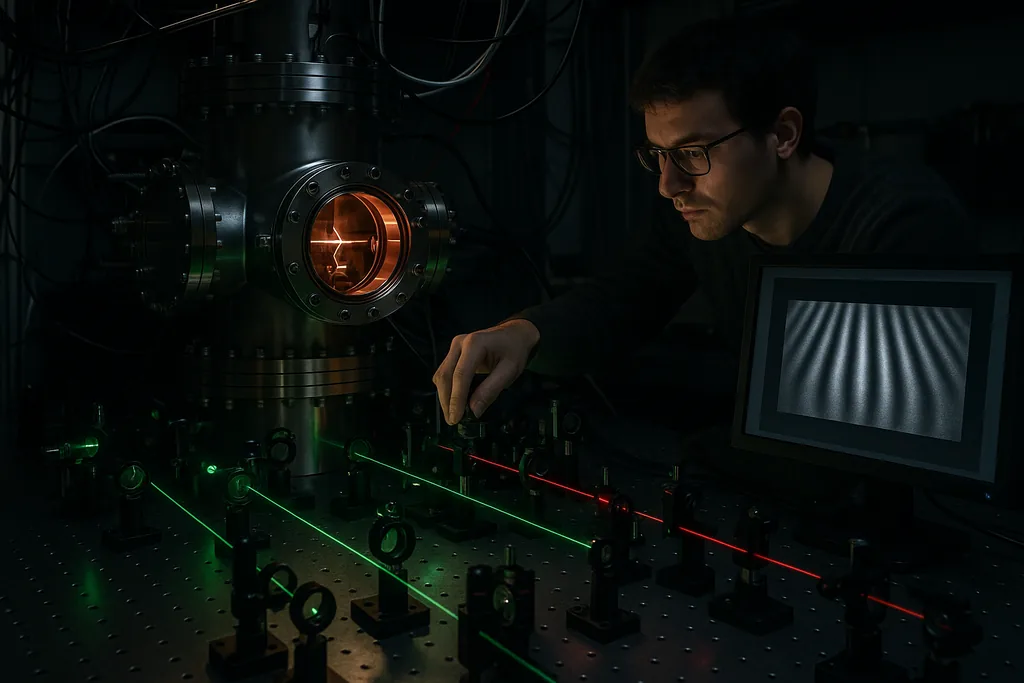

Conventional quantum gas microscopes produce exquisite images of where atoms sit and how spins or densities correlate in space, but they largely miss the phase — the complex sign and coherence — of the underlying many‑body wavefunction. The many‑body phase microscope closes that gap by turning the cold atom cloud itself into an interferometer. The protocol uses time‑domain matter‑wave lenses and Raman pulses in Fourier space to convert momentum differences into controlled spatial displacements, then reads out interference fringes with spin resolution. By varying the Raman phase and analysing the resulting fringe contrast across many lattice sites, the experiment extracts off‑diagonal single‑particle correlators — the equal‑time Green's function g(d) — and even non‑equal‑time correlators that carry spectral information.

How the microscope reveals hidden quantum correlations in practice

Experimentally the method is ambitious but rooted in techniques already familiar to ultracold‑atom groups: harmonic traps for temporal lensing, Raman transitions for coherent spin‑momentum control, and high‑resolution, spin‑resolved imaging. Reported figures of merit in the protocol include a magnification of about 93× between the object and the final image plane, thanks to carefully chosen trap frequency ratios and time‑domain lensing operations. That magnification is what lets tiny momentum differences become resolvable spatial fringes on a camera.

What microscopic quantum order means for materials science

When physicists talk about quantum order they mean more than a repetitive pattern of positions; they mean structure in the wavefunction itself — phase relationships, entanglement and long‑range coherence that define superconductivity, topological order and other emergent phenomena. These features are often invisible to probes that measure only charge density or local spin orientation. A microscope that images phase and off‑diagonal correlators therefore gives a direct picture of the order parameter instead of an inference from transport or bulk spectroscopy.

Access to that information matters because many theories of high‑temperature superconductors, fractional quantum Hall states and correlated topological materials predict subtle phase textures and non‑local correlators. Being able to compare those predictions with a real‑space, phase‑sensitive image would accelerate model validation and help identify which microscopic mechanisms actually produce the exotic phases researchers seek to harness.

Complementary advances in solid‑state probes

The new matter‑wave microscope sits within a wider wave of microscopy innovation aimed at exposing hidden quantum structure. For example, theoretical work shows that standard scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM), when combined with carefully placed impurities and quasiparticle‑interference analysis, can reveal spin textures in altermagnetic Lieb‑lattice systems without a spin‑polarised tip. Separately, angle‑resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) experiments at synchrotrons have detected many‑body multiplet features in layered Mott insulators such as NiPS3 that evade mean‑field descriptions. Together these advances underline a trend: by pushing measurement protocols beyond conventional observables, experiments are prising open the internal structure of correlated states.

But the platforms differ. The matter‑wave microscope is tailored to ultracold atoms where Hamiltonians can be engineered cleanly and coherently, giving straightforward interpretation of measured correlators. STM and ARPES are rooted in real materials and have the advantage of directly addressing candidate quantum materials, but they contend with disorder, phonons and coupling to environments. Both approaches are complementary: cold‑atom microscopes can realise and visualise model Hamiltonians with tunable parameters, while solid‑state probes test which elements of those models survive in the messy reality of materials.

Technical challenges and the road to materials‑scale imaging

The proposal is elegant but not trivial to implement. Precise timing, phase stability of Raman beams, and control over trap anharmonicities are all critical: any uncontrolled phase noise will wash out the very fringes the method seeks to measure. Spin‑resolved detection with single‑site fidelity remains demanding across large arrays, and the analysis of interference patterns to extract many‑body correlators requires careful statistical averaging and error modelling.

More fundamentally, the protocol is presently best suited to cold‑atom emulators of lattice models rather than direct imaging of electrons in a solid. Bridging that gap will require either transferring concepts (for example, momentum‑space manipulation) into novel solid‑state measurement geometries or using cold‑atom results as a clean benchmark to interpret more indirect solid‑state signals. Even so, within the cold‑atom arena the technique could be deployed rapidly to test competing theories for pairing, topological order and other quantum orders that have been difficult to pin down.

Potential near‑term experiments and longer‑term impact

Near term, groups running fermionic quantum gas microscopes can aim to implement the lensing and Raman sequence on Hubbard‑type setups to map pairing symmetry directly, or to diagnose coherence lengths and spectral functions across interaction‑tuned phase transitions. The method also opens routes to study dynamics by extracting non‑equal‑time Green's functions: that is, how excitations propagate and decay — a central question in nonequilibrium many‑body physics.

Longer term, the ability to image phase and off‑diagonal correlators will be a powerful tool in quantum‑materials design. Directly visualising how order parameter textures respond to impurities, strain or interfaces could shorten the feedback loop between theory, simulation and materials synthesis. In the broader scope of quantum technology, phase‑sensitive microscopy may help diagnose error processes in engineered many‑body states used for sensing or computation.

Sources

- ArXiv (Protocols for a many‑body phase microscope: From coherences and d‑wave superconductivity to Green's functions)

- TU Dortmund University (research group of Christof Weitenberg)

- Kyoto University (research group of Luca Asteria)

- Ludwig‑Maximilians‑Universität München (Fabian Grusdt and collaborators)

- ArXiv (Krylov space perturbation theory for quantum synchronization in closed systems)

- University of Würzburg (theoretical work on STM and altermagnets)

- Wrocław University of Science and Technology and RWTH Aachen University (ARPES studies of NiPS3)

- Elettra Synchrotron (NanoESCA beamline used in micro‑ARPES measurements)

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!