It’s historic: two black holes have just been photographed together

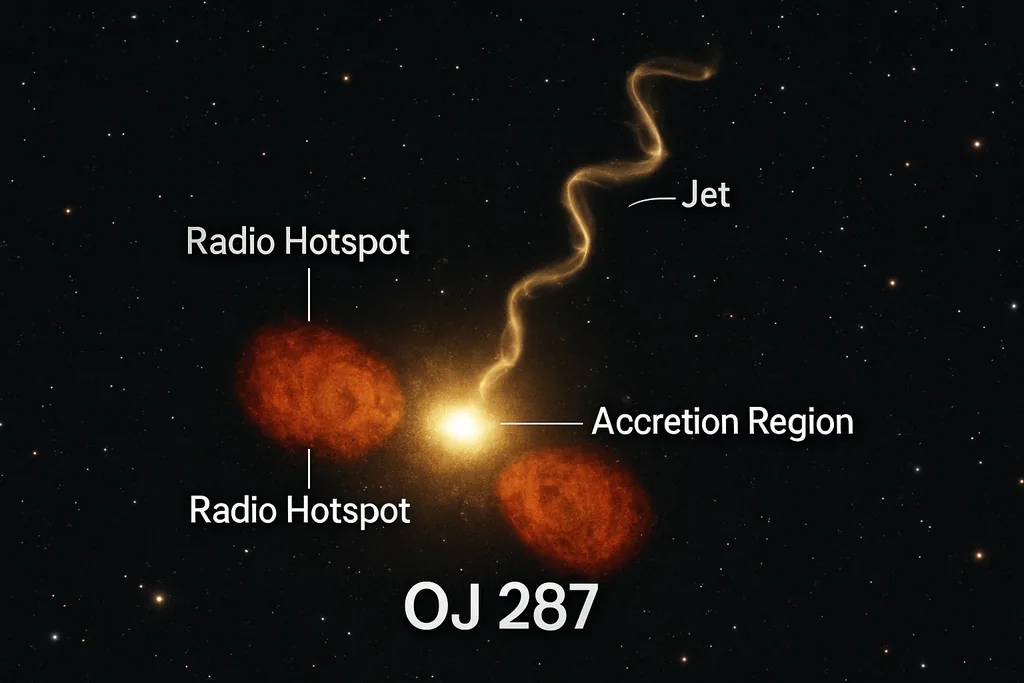

On 9 October 2025 an international team published a radio image that, for the first time, shows two supermassive black holes sharing the same orbit inside the blazar known as OJ287 — a discovery the team calls historic and that resolves a long-standing astronomical puzzle. The two compact radio sources sit where independent orbital models predicted they should be, and the smaller companion appears to launch a corkscrewing jet that looks as if a garden hose is being spun while spraying particles at near light speed. This interpretation, and the image itself, are built from very long baseline radio interferometry that combined Earth telescopes with archival space‑radio data and matches decades of timing and optical flare predictions for OJ287.

It’s historic: two black holes in OJ287

OJ287 has been a thorn and a promise for astronomers for more than a century: the object was visible on archived 19th‑century photographic plates and, since the 1980s, its regular 12‑year pattern of bright optical outbursts has been argued to arise from a binary black‑hole engine. That model — refined over decades by groups led from the University of Turku, Tata Institute and others — predicted the timing and geometry of repeated flares, and the new radio image locates two compact radio emitters exactly where those models place the primary and secondary black holes. For many researchers this is the first direct, spatial confirmation that the brightness oscillations really do come from a bound pair rather than from a single, precessing jet.

It’s historic: two black holes — instruments and imaging technique

Capturing two black holes in mutual orbit demanded the sharpest radio eyes available. The team used very long baseline interferometry (VLBI), combining signals from an international array of ground radio telescopes and space‑based baselines provided by the RadioAstron (Spektr‑R) mission, whose antenna once reached roughly halfway to the Moon and so dramatically improved angular resolution. That ground‑plus‑space VLBI dataset yields an effective resolving power equivalent to imaging a coin on the Moon and was essential to separate the two compact radio sources inside OJ287's bright core. Crucially, the black holes are inferred from their radio jets and compact hotspots in the interferometric map — the holes themselves remain invisible, revealed only by the energetic structures they launch.

Masses, separation and what the picture tells about gravity

As an inference from those measured masses and the 12‑year period, Keplerian dynamics give a rough semi‑major axis of order 1–2×10^4 astronomical units (about 0.05–0.1 parsec, or a few‑tenths of a light‑year). That number is an approximate, Newtonian estimate derived from the published masses and orbital period and should be read as an order‑of‑magnitude physical scale rather than a direct measurement reported in the radio image. The important point is that the pair are extremely compact on astronomical terms, and at the distance of OJ287 — about five billion light‑years from Earth — their angular separation on the sky is tiny, which is why space‑baseline VLBI was needed to resolve them.

OJ287 has already been used as a laboratory for testing general relativity: predicted impact flares and periastron precession in the binary model have provided indirect tests of relativistic dynamics and energy loss via gravitational waves. The new direct image does not by itself replace those tests, but it anchors the system’s geometry in space and gives observers a rare chance to follow relativistic orbital motion and changing jet orientation in real time — a direct probe of strong‑field gravity, space‑time precession and the coupling between orbit and accretion physics.

Jet behaviour, ambiguity and why follow‑up matters

What the image means for future observations and gravitational waves

Finding a resolvable supermassive binary at parsec/sub‑parsec scales is a big deal for multi‑messenger astronomy. Systems like OJ287 are candidate emitters of nanohertz gravitational waves that pulsar timing arrays attempt to measure. A spatially located and modelled binary provides an astrophysical anchor for those low‑frequency searches and gives theorists a well‑specified target to predict waveforms and inspiral times. On shorter timescales, monitoring the jet orientation as the orbit proceeds will test models of jet launching, magnetic geometry and disk–secondary interactions; researchers are already planning VLBI follow‑ups that will track the expected ‘wagging’ of the secondary's jet through multiple phases of its 12‑year orbit.

How this image answers long‑running questions

People have asked for decades whether active galactic nuclei that show periodic brightness variations hide two black holes or just complex accretion and jet physics. The OJ287 image does not single‑handedly settle every alternative, but it does provide a spatial confirmation that matches a long history of timing predictions — something that indirect tests could never fully supply. By tying the radio hotspots to independently derived orbital models, the work reduces the viable parameter space for alternative one‑black‑hole explanations and establishes a new observational benchmark for studies of binary evolution, relativistic precession and jet response to orbital motion.

Next steps and where to look

Because the claim rests on a complex VLBI reconstruction and on matching modeled orbital phases, the field will now pivot to verification. That means more VLBI with dense baseline coverage, new space‑VLBI concepts that restore RadioAstron‑level baselines, multiwavelength campaigns to tie radio structure to optical and X‑ray flares, and careful polarimetric monitoring to test whether the twisted structure really is a rotating jet. If repeat imaging shows the secondary’s jet swinging in the way current models predict, the case will move from highly persuasive to incontrovertible — and OJ287 will become the closest thing we have to a directly observed, slowly evolving supermassive binary laboratory.

Sources

- University of Turku (press release and research materials on OJ287)

- The Astrophysical Journal (peer‑reviewed paper describing the radio imaging results)

- RadioAstron / Spektr‑R mission (space VLBI observatory used in the dataset)

- Astronomy & Astrophysics (VLBI jet and polarization studies, Event Horizon Telescope team papers)

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!