When the missing mass shows up as a puzzle

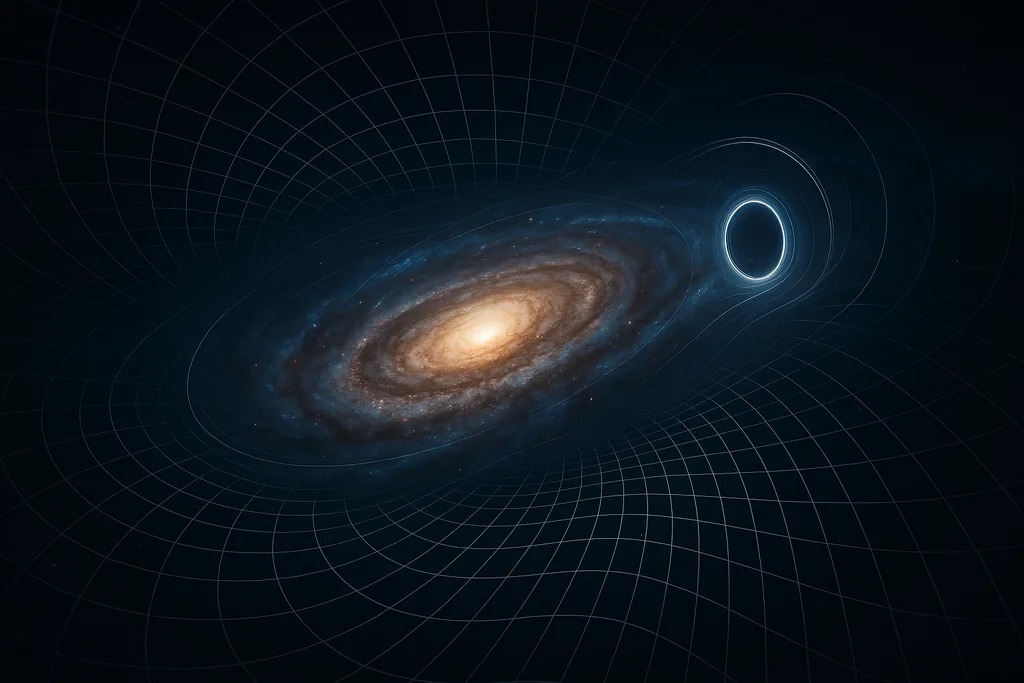

On February 7, 2026 a wave of coverage and a new technical proposal pushed an old question back into the headlines: is dark matter real? theory — could the effects we attribute to a vast invisible particle population instead be produced by gravity behaving strangely on large scales? The new idea is a contemporary reworking of alternate-gravity thinking and a separate line of work that uses a "warped" fifth dimension to hide fermions from our detectors; both approaches force a blunt re-examination of the data that made dark matter the default in the first place.

dark matter real? theory: a gravity-first alternative

The empirical starting point is simple and stubborn. Beginning with Vera Rubin's galaxy rotation measurements and running through precision maps of the cosmic microwave background, multiple independent observations show more gravitational pull than can be supplied by ordinary atoms. The usual response — and the mainstream consensus for four decades — is dark matter: a non-luminous substance that dominates the matter budget of the universe.

Yet modified-gravity proposals, collectively described as alternatives to particle dark matter, offer another route. The best-known of these is Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND), which adjusts the relation between acceleration and force at extremely low accelerations and can reproduce the flat rotation curves of many spiral galaxies with fewer free parameters than naïve dark-matter fits. MOND-style models succeed at the scale of individual galaxies but run into trouble with other observations — notably the way mass is distributed in galaxy clusters, the detailed pattern of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) acoustic peaks and the formation of large-scale structure.

Proponents of revived gravity-first approaches argue that those difficulties don't strictly rule out all modifications of gravity. New theoretical frameworks attempt to change the strength or form of gravity at particular length scales, or to add additional gravitational degrees of freedom that mimic the clustering behaviour of dark matter without invoking new particle species. These models must be tuned to reproduce the successes of General Relativity on solar-system scales while deviating only where data suggest a mismatch, which is a hard constraint but not an impossible one.

dark matter real? theory vs particle models

The alternative on the other side of the ledger is the particle hypothesis: dark matter is made of one or more new kinds of particles that interact very weakly with light and ordinary matter. That framework explains a broad range of phenomena in a single conceptual move: extra mass added to galaxies and clusters, the gravitational lensing patterns we observe, and the signature imprinted on the CMB and the growth of structure. It also opens straightforward experimental paths — direct detection in underground labs, indirect detection via decay or annihilation signals, and production attempts at colliders.

So far, those direct searches and collider campaigns have not produced a decisive detection, which keeps the door open for alternatives. The recent theoretical work covered in the bundle does not merely tweak gravity: another strand resurrects a version of the Randall–Sundrum style models from the late 1990s in which a warped extra dimension houses a dark sector. In that scenario — described in a recent research paper and translated for broader audiences by a few outlets — ordinary fermions can acquire bulk masses that appear as long-lived relics in the extra dimension. From our four-dimensional perspective those relics behave like dark matter, but their underlying origin is geometrical rather than a new stable particle in the Standard Model's three spatial dimensions.

What the data currently prefer

Different lines of observation weigh differently in the balance. Galaxy rotation curves and some dwarf-galaxy internal dynamics are where modified gravity has its greatest successes. On the other hand, the Bullet Cluster and other colliding galaxy clusters provide a very strong visual test: in those violent collisions, the bulk of the visible gas (which emits X-rays) is stripped and slowed while the gravitational potential traced by weak lensing appears offset from the baryonic matter. That displacement is naturally explained if most mass sits in collisionless particles that pass through each other — exactly what particle dark matter would do — and is difficult to reproduce using a single, simple modification of gravity.

How a warped extra dimension changes the conversation

The warped extra-dimension (WED) proposal merges elements of particle dark matter and modified gravity. It treats the dark sector as physically real but located in an extra-dimensional pocket where its dynamics are governed by different rules. That architecture can generate effective dark-matter behaviour in our observable universe while sidestepping some null results from direct searches, because the dark relics don't couple to our detectors in the usual way. Importantly, authors of WED proposals point to gravitational-wave detectors and forthcoming precision cosmological surveys as the most promising ways to falsify or confirm the idea: the extra-dimensional relics would influence structure formation and possibly leave signatures in the stochastic gravitational-wave background or in lensing statistics at particular scales.

How experiments could decide whether dark matter is a particle or modified gravity

There are several observational strategies that together can separate the hypotheses.

- Collision tests at cluster scales: More colliding clusters like the Bullet Cluster, observed with deeper X-ray mapping and high-quality weak-lensing reconstruction, help reveal whether the gravitational potential can be cleanly separated from baryons — a strong discriminator against simple modified-gravity explanations.

- Precision cosmology: CMB polarisation and next-generation galaxy surveys pin down the timing and rate of structure growth. Particle dark matter predicts a particular growth history; many modified-gravity models predict different scale-dependent growth that can be tested.

- Direct and indirect detection: If underground detectors or gamma-ray telescopes detect an unambiguous dark-matter particle signal, that would settle the debate. Conversely, an extended sequence of null results does not prove gravity is wrong but does drive theorists away from particle models in parameter space.

- Gravitational waves and lensing statistics: The WED proposals highlight gravitational-wave backgrounds and subtle lensing anomalies as potential smoking guns. LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA and future detectors, together with wide-field lensing surveys, will explore those signatures.

Where modified gravity still struggles

Most modified-gravity frameworks must be extended or made more complex to satisfy constraints from multiple scales simultaneously. They often require new fields or screening mechanisms to reduce deviations in the solar system while producing large effects on galactic scales. Each additional ingredient risks making the theory less predictive, and that is why many cosmologists remain cautious about abandoning particle dark matter without robust, independent evidence to the contrary.

Why the debate matters beyond labels

This is not just academic hair-splitting. The outcome determines the experimental roadmap and the deep physics we infer about fundamental forces, extra dimensions and the early universe. If dark matter is a particle, it points to new microphysics beyond the Standard Model. If it is an emergent effect of gravity or of extra-dimensional geometry, it implies General Relativity is incomplete in a specific, testable way — and that would reshape theoretical physics in profound ways.

For now the safest scientific position is pluralist: keep searching for particles while developing and testing alternative gravitational theories. The coming decade will bring higher-fidelity lensing maps, deeper cluster catalogs, gravitational-wave backgrounds and more sensitive direct-detection instruments — the combination of which should considerably narrow the possible explanations.

Sources

- European Physical Journal C (research paper on warped extra dimensions and fermionic dark matter)

- Randall–Sundrum (original warped extra-dimension model, 1999)

- Planck Collaboration (cosmic microwave background observations)

- LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA collaborations (gravitational-wave detectors)

- Institutions and research groups in Spain and Germany involved in the recent WED study

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!