Low-Frequency Laser Model Offers Potential Shortcut to Practical Nuclear Fusion

Scientists have long sought a way to overcome the intense electrostatic repulsion between atomic nuclei without relying solely on the extreme temperatures found in the cores of stars. In a significant theoretical advancement published in the journal Nuclear Science and Techniques, researchers have proposed a new mechanism that utilizes intense, low-frequency laser fields to manipulate collision energies. This approach facilitates quantum tunneling, potentially lowering the immense physical and thermal barriers that currently hinder the generation of clean, limitless fusion energy.

The Challenge of the Coulomb Barrier

The pursuit of controlled nuclear fusion—the process that powers the sun—has been defined by a singular, daunting obstacle: the Coulomb barrier. Because atomic nuclei are positively charged, they exert a powerful electrostatic repulsion against one another. To achieve fusion, two nuclei must be brought close enough for the strong nuclear force to take over and bind them together. Traditionally, this requires heating fuel, such as isotopes of hydrogen, to temperatures exceeding tens of millions of degrees Kelvin. At these temperatures, the nuclei move with sufficient kinetic energy to overcome their mutual repulsion.

However, maintaining these "solar" conditions on Earth presents monumental engineering challenges. Current methods, such as Magnetic Confinement Fusion (MCF) and Inertial Confinement Fusion (ICF), require massive energy inputs to sustain the plasma state and prevent the fuel from touching the reactor walls. The limitations of traditional thermal heating are clear: the energy required to reach these temperatures often rivals or exceeds the energy produced by the reaction itself. Consequently, the search for a more efficient catalyst to bridge the gap between low-temperature states and the fusion threshold has become a priority for theoretical physicists.

A New Theoretical Framework for Fusion

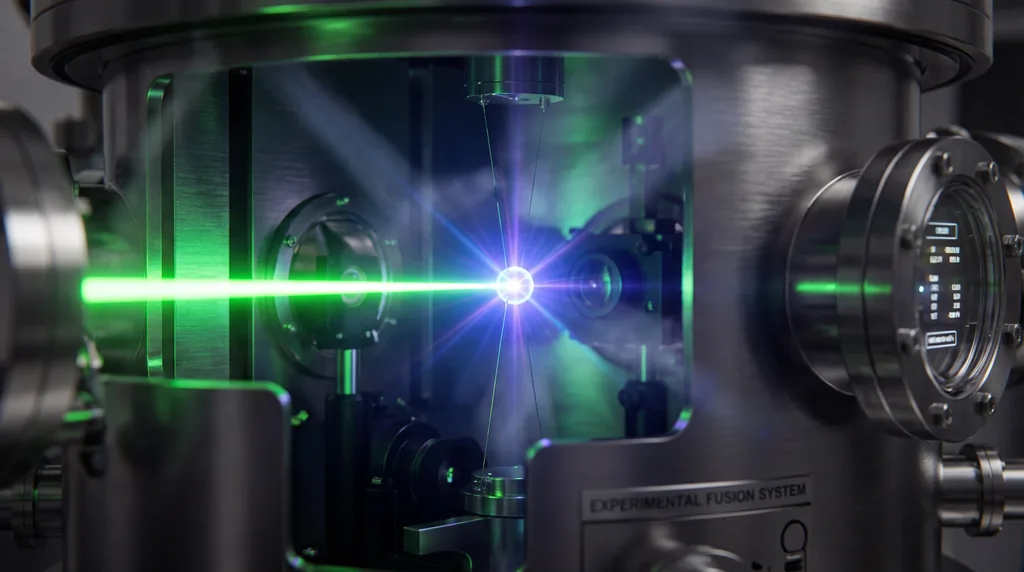

A research team led by Assistant Professor Jintao Qi of Shenzhen Technology University, along with Professor Zhaoyan Zhou of the National University of Defense Technology and Professor Xu Wang of the Graduate School of the China Academy of Engineering Physics, has introduced a compelling alternative. Their study, titled "Theory of laser-assisted nuclear fusion," suggests that the brute force of thermal heating could be supplemented—or perhaps mitigated—by the strategic application of intense laser fields. Unlike traditional approaches where lasers are used primarily to compress fuel pellets, this framework proposes using the laser field to directly modify the quantum dynamics of the colliding nuclei.

The study highlights a surprising finding regarding laser frequency. While high-frequency lasers, such as X-ray free-electron lasers, carry more energy per photon, the researchers found that low-frequency lasers—specifically those in the near-infrared spectrum—are significantly more effective at enhancing fusion rates. This counterintuitive result stems from the ability of low-frequency systems to drive "multi-photon processes." Under these conditions, the interacting nuclei can absorb and emit a vast number of photons during a single encounter, effectively reshaping their collision energy distribution in a way that high-frequency photons cannot match.

The Mechanics of Quantum Tunneling

At the heart of this discovery is the phenomenon of quantum tunneling. In the quantum realm, particles do not always need enough energy to "roll over" a potential energy barrier; instead, they have a statistical probability of "tunneling" through it. By applying an external laser field, the researchers demonstrated that it is possible to broaden the effective collision energy distribution of the reacting nuclei. Instead of a narrow energy range dictated by the thermal environment, the laser field creates a wider distribution with significantly more weight at higher effective energies.

The mathematical modeling provided by Assistant Professor Qi and his colleagues shows that the laser does not merely add energy; it modifies the potential landscape the nuclei inhabit. This "laser-assisted" tunneling allows nuclei with relatively low initial kinetic energies to pass through the Coulomb barrier at rates previously thought impossible without massive thermal acceleration. Essentially, the laser acts as a quantum catalyst, increasing the reaction cross-section—the probability that a collision will result in fusion—without requiring a commensurate increase in the overall temperature of the system.

Bypassing Solar Conditions

The quantitative implications of this model are striking. Using the deuterium-tritium (D-T) reaction as a benchmark, the authors calculated the impact of a low-frequency laser with a photon energy of 1.55 eV. For collisions at 1 keV (a relatively low energy in fusion terms), a laser intensity of 1020 W/cm2 boosted the fusion probability by three orders of magnitude. When the intensity was increased to 5 x 1021 W/cm2, the enhancement reached a staggering nine orders of magnitude compared to a field-free environment.

In practical terms, this means that with the assistance of an intense low-frequency laser, a 1 keV collision could achieve an effective fusion cross-section comparable to a 10 keV collision in a traditional reactor. By engineering the energy distribution of the nuclei rather than relying solely on thermal bulk heating, the researchers suggest a possible route to narrowing the gap between experimental conditions and practical fusion. This could lead to a redesign of inertial confinement systems, where the laser's role shifts from simple compression to a more nuanced manipulation of nuclear interactions.

A Unified Framework for Laser-Nuclear Physics

The work organizes laser-assisted fusion behavior into a unified theoretical framework that spans a wide range of frequencies and intensities. According to the authors, this framework demonstrates that intense laser fields can, in principle, relax the stringent temperature requirements associated with controlled fusion while still utilizing conventional fuel cycles. This contribution is particularly valuable for the emerging field of laser nuclear physics, providing a roadmap for how light-matter interactions can be used to control processes traditionally reserved for the high-energy environments of particle accelerators or stellar interiors.

The researchers emphasize that their current model focuses on an idealized two-body system. This simplification was necessary to isolate and understand the fundamental mechanism of laser-reshaped tunneling. However, they acknowledge that the transition from theory to a functioning reactor will be complex. "Realistic fusion plasmas involve many-body effects, complex laser-plasma interactions, and various channels for energy dissipation," the team noted in their report. These factors must be meticulously integrated into the model to determine how these enhancements behave in a dense, turbulent plasma environment.

Roadmap to Experimental Validation

The next phase of this research involves moving from the idealized vacuum of theoretical physics to the complex reality of laboratory testing. The researchers point to the rapid global expansion of high-intensity laser facilities as a primary motivator for their work. Facilities capable of reaching the intensities described in the study—such as the Extreme Light Infrastructure (ELI) in Europe or various high-power laser labs in China and the United States—could soon be used to validate these predicted boosts in fusion probability.

Future work will focus on extending the theory to include "collective behavior" and "screening" effects within a plasma. In a real-world reactor, the presence of other electrons and ions can shield the nuclei, potentially altering how the laser field interacts with the individual fusion partners. If the predicted three-to-nine-order-of-magnitude enhancements hold true in these more complex environments, the pathway to commercial fusion energy could be significantly shortened. By providing theoretical guidance for the design of future experiments, the team from Tokyo, Shenzhen, and the China Academy of Engineering Physics has laid the groundwork for a potential paradigm shift in how we approach the "holy grail" of clean energy.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The study represents a pivot in fusion research strategy: moving away from the brute-force application of heat and toward the precision manipulation of quantum states. If intense, low-frequency lasers can indeed act as a "shortcut" through the Coulomb barrier, the engineering requirements for future reactors might become substantially less prohibitive. While the road to a carbon-free, fusion-powered grid remains long, theoretical tools like those developed by Professor Qi and his colleagues provide the necessary coordinates for the next generation of experimental physicists to follow.