The Hidden Architecture of Matter: Mapping the Quark-Gluon Sea with Hydrogen Isotopes

For decades, physicists have sought to map the chaotic internal dynamics of the proton and neutron, the fundamental building blocks of the atomic nucleus. Despite their ubiquity, the precise distribution of the particles within them—quarks and the gluons that bind them—has remained elusive due to the extreme scales and forces involved. However, a landmark experiment conducted at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility has achieved a new level of precision in this subatomic cartography. By utilizing the simplest element in the universe, hydrogen, and its heavier isotopes, researchers have sharpened our view of the internal structure of matter, reducing experimental uncertainties that have persisted for a generation.

The research, recently detailed in reports from Los Angeles by Clarence Oxford, centers on the unique properties of hydrogen nuclei. Hydrogen sits at the apex of the Periodic Table because its most common form, protium, consists of a single proton. While protons are stable and easily studied in the laboratory, neutrons present a significant challenge for nuclear physicists. An isolated neutron is unstable, decaying in approximately ten minutes, which prevents scientists from using them as stationary targets. To circumvent this, the collaboration at Jefferson Lab turned to deuterium—an isotope of hydrogen containing one proton and one neutron. By comparing the scattering of electrons off protium and deuterium, the team could effectively isolate the behavior of the neutron, using the two isotopes as a high-definition mirror to reflect the differences in their internal architectures.

Probing the Nucleus with the CEBAF

The methodology behind this discovery relied on the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF), a premier DOE Office of Science user facility that serves a global community of over 1,650 nuclear physicists. During the experiment, researchers directed a high-intensity, high-energy electron beam onto targets of liquid hydrogen and deuterium. As these electrons collided with the nucleons, they scattered at various angles and energies. These scattered particles were then meticulously recorded by the Super High Momentum Spectrometer (SHMS) located in Experimental Hall C. This process, often referred to as Deep Inelastic Scattering (DIS), allows physicists to "see" inside the proton and neutron by using electrons as microscopic probes that strike individual quarks.

By recording the energies and angles of the outgoing electrons, the research team determined a ratio of "cross sections," or the statistical probability that an electron would interact with a target in a specific way. Comparing the cross sections of the deuteron against those of the lone proton allowed the team to strip away common variables and focus on the distinct contributions of the neutron. This comparative approach is vital because it cancels out many systematic experimental "noises," providing a cleaner signal of the quark distributions that define the internal state of the nucleon.

Refining the Quantum Chromodynamics Framework

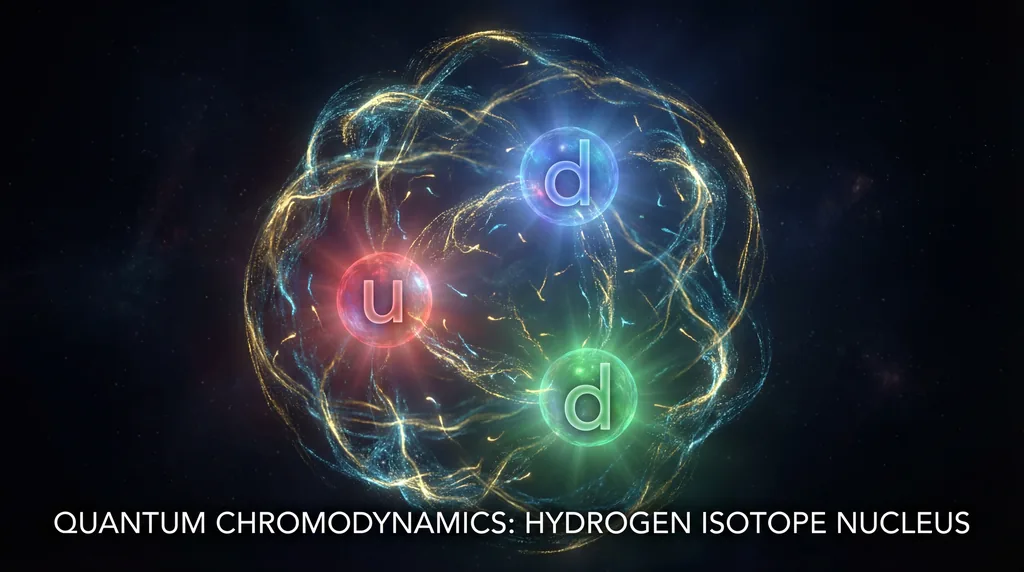

The findings provide critical data for Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), the theoretical framework that describes the strong interaction—the force that holds quarks and gluons together. Within the nucleon, "valence" quarks determine the identity of the particle; a proton contains two up quarks and one down quark, while a neutron consists of two down quarks and one up quark. However, these valence quarks exist within a "sea" of virtual quarks and gluons that are constantly popping in and out of existence. The Jefferson Lab experiment focused on the valence quark region, specifically measuring the relative probabilities of scattering from down quarks versus up quarks as a function of their momentum.

The precision of this new measurement is unprecedented. Historically, uncertainties in the proton-to-deuteron cross section ratio in this kinematic region hovered between ten and twenty percent. The recent Jefferson Lab experiment has successfully pushed this uncertainty below five percent. This dramatic improvement allows theorists to refine global fits and models of quark distributions with a level of confidence previously unattainable. It provides a more accurate map of how momentum is shared among the constituent particles of the nucleus, offering a clearer picture of the nucleon's internal momentum budget.

Implications for the Standard Model and Beyond

Beyond simply refining existing models, the data holds significant implications for the broader field of particle physics. The experiment extended into higher kinematic regions than previous studies, broadening the phase space over which the quark structure can be tested. This is particularly relevant for "quark-hadron duality," a phenomenon where the behavior of matter can be described either through the lens of individual quarks and gluons or as collective composite particles like protons and neutrons. Understanding this transition is essential for a complete description of the strong force.

Furthermore, these high-precision measurements act as a baseline for the Standard Model of particle physics. Accurate knowledge of quark distributions is a prerequisite for identifying "new physics" at larger facilities like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). When physicists look for anomalies in high-energy collisions, they must first subtract the known backgrounds of Quantum Chromodynamics. The Jefferson Lab data provides a more stable foundation for these calculations, ensuring that any deviations found in future experiments are truly indicative of new phenomena rather than errors in our understanding of basic nucleon structure.

A Collaborative Path Forward

The success of the experiment was the result of close coordination between several major research efforts, including the EMC Effect program and the BONuS12 and MARATHON collaborations. By comparing different experimental techniques and kinematic coverage, these groups aim to better understand "nuclear medium effects"—the subtle ways in which the environment of a nucleus changes the behavior of the protons and neutrons within it. The integration of this new dataset into the worldwide repository of nuclear information provides a shared resource that will benefit the community for years to come.

Looking ahead, the researchers at Jefferson Lab anticipate that these results will pave the way for even more ambitious projects, such as those planned for the upcoming Electron-Ion Collider (EIC). As nuclear physics enters an era of "high-definition" exploration, the humble hydrogen atom remains an indispensable tool. By pushing the frontiers of precision, this experiment has not only mapped the internal sea of quarks and gluons but has also brought us one step closer to understanding the fundamental origin of mass and the very glue that holds the visible universe together.