Neural nets that learn the unseen landscapes inside equations

This week a group of mathematicians and engineers published a method showing how machine learning accurately recovers unknown functions that sit inside partial differential equations — the mathematical workhorses used to describe heat, fluids, populations and more. The team, with lead contributions from researchers at the University of Oxford and collaborators in Canada, embeds a neural network directly into the PDE as a surrogate for the unknown spatial function and trains the whole system against observed steady-state data. The result is not just a fitted number or parameter: it is a function the model can evaluate anywhere the PDE makes sense, turning incomplete equations into working predictive models.

The advance tackles a long-standing inverse problem. Many real-world PDEs contain terms we cannot measure directly — an environmental stimulus, a spatially varying interaction kernel in a population model, or a heterogeneity in a flow field — and those unobserved functions cripple forecasting. By letting a neural network stand in for the missing piece and optimising how the forward model’s output matches observed states, the researchers bypass some of the fragile steps common in earlier approaches, such as differentiating noisy measurements. Their loss function minimises a fixed-point residual — effectively forcing the numerically computed steady state of the forward model to match the data — which stabilises training and reduces the need for harsh data pre-processing.

How machine learning accurately recovers functions embedded in PDEs

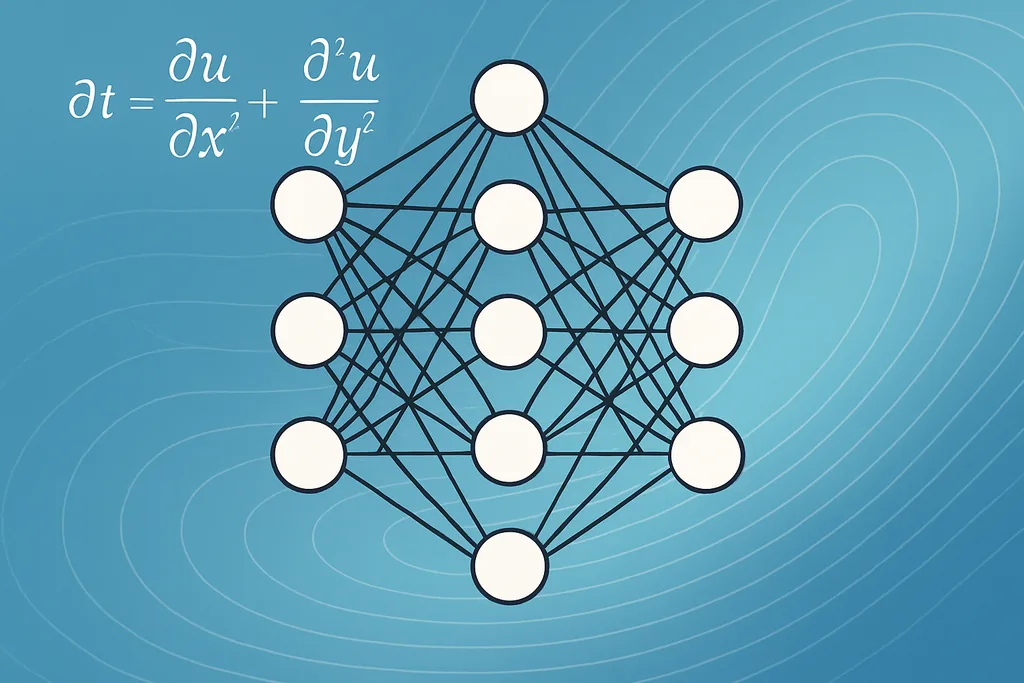

The core technical trick is simple in idea and delicate in practice. Rather than tuning a handful of scalar coefficients, the team represents the unknown spatial term as a neural network with adjustable weights. The PDE solver and the network are coupled: the solver maps a candidate function to a steady-state solution, and the training loop nudges the network so the PDE solution aligns with measurements. This is an example of a broader family of methods known as physics-informed learning, where physical constraints are built into the architecture instead of learned purely from scratch.

Practically, the optimisation target they use — the fixed-point residual norm — vanishes exactly for equilibria of the forward model. That matters because it avoids taking numerical derivatives of noisy observational data, a common source of instability in inverse problems. It also makes the procedure compatible with sparse, irregularly sampled measurements: the team shows recovery works with surprisingly little data, provided the observations are informative enough about the underlying function's effect on the solution. Variants of this idea are already appearing in other fields: hybrid quantum-classical physics‑informed neural networks have been proposed for reservoir flow simulations, while differentiable algorithmic models bring guarantees and scale to combinatorial problems. These developments share the same theme — use structure from the physics or algorithm to guide learning, rather than letting black‑box models wander freely.

From a machine‑learning perspective this is equation discovery at the functional level rather than symbolic regression of whole operators. Neural networks act as universal approximators: given sufficient capacity and the right inductive bias, they can represent smooth unknown functions that would otherwise require bespoke parameterisations. Training extracts those functions by asking: which landscape, when plugged into the PDE, produces the data we observe? Where symbolic extraction is needed, researchers can follow the functional recovery with a model‑compression or sparse‑regression step to produce human‑readable expressions, but the immediate output — a working function you can evaluate at new points — is already a valuable scientific deliverable.

Limits where machine learning accurately recovers — identifiability, noise and data design

Promises aside, the method has clear boundaries. The team demonstrates success with exact, noise‑free simulations and then explores how performance degrades with realistic imperfections. Two issues stand out: structural identifiability and measurement noise. Structural identifiability is an analytical property of the PDE–data pair: some functions cannot be uniquely determined from a given set of observations because they leave the observed outputs unchanged. The researchers emphasise that a single steady‑state snapshot is often insufficient; at least two independent solutions, or perturbations that probe different system responses, are normally required to constrain the inverse problem.

Noise and sparse sampling further complicate matters. Recovery remains viable under sparse sampling in many of their synthetic tests, but the accuracy drops as observation noise increases. The sensitivity varies with the problem: some PDEs amplify measurement errors in predictable ways, while others average them out. That means practical deployments must pay careful attention to experimental design: where and when to sample, how to generate multiple informative solutions, and which regularisation terms to include in training to prevent the network from fitting the noise rather than the signal.

Reliability is a layered question. Machine learning accurately recovers hidden functions when three ingredients align: the unknown function has an imprint on the observable solution, the training protocol encodes the correct physical constraints, and the data sample spans enough of the solution manifold to rule out alternative explanations. When those conditions fail, recovered functions can be misleadingly plausible but wrong. The study’s systematic exploration of failure modes is useful precisely because it converts vague warnings into testable diagnostics for practitioners.

Techniques, tools and complementary approaches

The paper sits within a growing toolbox of equation‑discovery methods. Physics‑informed neural networks (PINNs) and their quantum‑classical hybrids are one family: they bake differential operators into the loss and are especially attractive when the governing PDE is known but some terms are not. Message‑passing graph neural networks offer a different angle for problems with discrete structures, for example in materials or networked ecological systems, and can be designed to inherit algorithmic guarantees. Symbolic‑regression techniques — sparse regression, basis pursuit and other parsimonious‑model discovery methods — remain valuable when the goal is an interpretable analytic expression rather than a numerical surrogate.

Extraction of symbolic expressions from the learned function is an active research area. Practitioners often use a two‑stage pipeline: first learn a flexible neural surrogate that fits the data, then post‑process that surrogate with a sparse‑fitting or pruning step to distil a compact analytic form. That hybrid workflow combines the best of both worlds — the flexibility of neural nets to handle noise and complexity, and the interpretability of symbolic models that scientists can analyse and validate.

Applications across ecology, materials and fluid mechanics

Why this matters: if machine learning accurately recovers the unseen pieces of a model, you can convert descriptive snapshots into predictive tools. In ecology, the unknown function might be an environmental field or an interaction kernel that shapes population aggregation; recovering it lets managers forecast species distributions under new conditions. In materials and condensed‑matter models, spatial heterogeneities such as variable conductivity are frequently the unknowns that determine macroscopic behaviour, and a recovered function provides a direct input for design and control. The approach also complements work in reservoir engineering where hybrid quantum‑classical PINNs have been proposed to reduce computational cost while retaining physical fidelity when solving flow PDEs.

Across these domains the method reduces the friction between data collection and model deployment. Instead of rebuilding physics from scratch or overfitting phenomenological terms, scientists can let structure guide learning and still obtain usable, evaluable models. The practical gains will depend on how well experimenters can generate the multiple, informative system responses the method needs and on continued work to make training robust to realistic noise and modelling error.

Sources

- ArXiv (preprint: Learning functional components of PDEs from data using neural networks)

- Mathematical Institute, University of Oxford (Torkel E. Loman, Jose A. Carrillo, Ruth E. Baker)

- Department of Mathematics, Physics and Geology, Cape Breton University

- Department of Engineering, University of Oxford

- Yangtze University; King Abdullah University of Technology (Quantum‑Classical PINN reservoir simulation work)

- RWTH Aachen University; TU Munich; MIT; University of Cologne (graph neural network approaches to algorithmic problems)

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!