The Artemis Earthset: What Humans Will See During the First Crewed Lunar Mission in Fifty Years

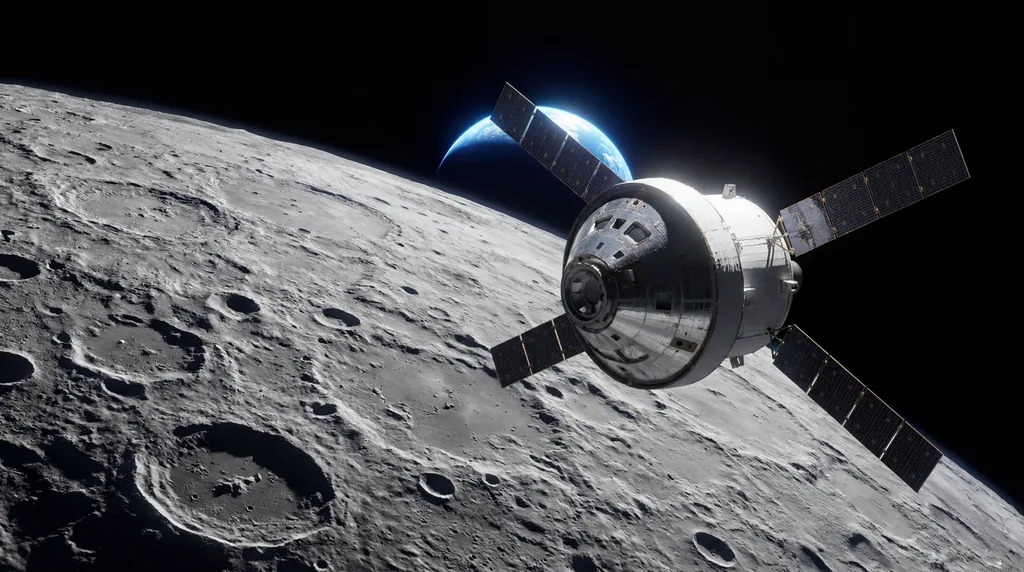

As NASA prepares for the Artemis II mission, a stunning "Earthset" image captured by the uncrewed Orion spacecraft offers a glimpse into the perspective future astronauts will soon share. This view, showing our home planet vanishing behind the lunar limb, marks a pivotal moment in the transition from robotic testing to human deep-space exploration. On November 21, 2022, eight billion people essentially disappeared from the view of the Orion spacecraft’s external cameras, obscured by the rugged, ancient horizon of the Moon. This photograph is not merely a visual triumph but a data-rich testament to the success of the Artemis I mission, which served as the rigorous proving ground for the systems intended to carry humanity back to the lunar surface.

The visual phenomenon of an "Earthset" is a perspective unique to lunar-bound voyagers. Unlike the sunset we experience on Earth, which is caused by the rotation of our planet, an Earthset viewed from a spacecraft near the Moon is often the result of orbital motion. In the snapshot taken on the sixth day of the Artemis I mission, the entire human population is reduced to a blue and white marble slipping behind the Moon's bright edge. This perspective emphasizes the profound isolation of deep-space travel and the technical precision required to navigate the vast gulf between Earth and its satellite. For NASA, this image served as a "check-out" of the spacecraft’s optical navigation systems and external monitoring cameras, ensuring that they could withstand the harsh radiation and lighting conditions of the lunar environment.

The Mechanics of the Mission: Distant Retrograde Orbit

The path taken to capture such an image was dictated by the complex physics of orbital mechanics. To reach its destination, the Orion spacecraft performed a powered flyby, bringing it within a mere 130 kilometers of the lunar surface. This close encounter was not just for observation; it was a high-stakes maneuver designed to utilize the Moon’s gravity. By executing a precisely timed engine burn during this flyby, Orion gained the necessary velocity to propel itself into a Distant Retrograde Orbit (DRO). This specific orbit was chosen for its inherent stability and the unique testing environment it provided for the spacecraft's long-term endurance in deep space.

A Distant Retrograde Orbit is characterized by two primary factors: its altitude and its direction. It is considered "distant" because it positioned Orion approximately 92,000 kilometers beyond the Moon at its furthest point. It is "retrograde" because the spacecraft traveled in the opposite direction of the Moon’s orbit around the Earth. This orbit allows a spacecraft to remain in a stable position relative to the Earth-Moon system with minimal fuel consumption. For NASA engineers, the DRO served as the perfect laboratory to monitor how Orion’s thermal protection systems, navigation sensors, and solar arrays performed when far removed from the protective magnetic influence of the Earth.

Surpassing Apollo: Records in Deep Space Exploration

The Artemis I mission was designed to push the boundaries of what human-rated spacecraft are capable of achieving. On November 28, 2022, while swinging through its wide orbit, Orion reached a maximum distance of just over 400,000 kilometers from Earth. In doing so, it officially exceeded the record set by the Apollo 13 mission in 1970 for the most distant spacecraft designed for human space exploration. While Apollo 13 reached its record under emergency circumstances during a lunar flyby, Orion’s achievement was a planned demonstration of the spacecraft’s deep-space endurance and its ability to maintain communication with the Deep Space Network at extreme ranges.

Maintaining a human-rated vessel at such distances requires extraordinary engineering. The life support systems, though unoccupied during Artemis I, were monitored via thousands of sensors to ensure they could maintain atmospheric pressure, oxygen levels, and temperature for a future crew. The shielding was also a primary focus; at 400,000 kilometers, the spacecraft is exposed to significantly higher levels of cosmic radiation and solar flares than it would be in Low Earth Orbit. The success of this mission provided the telemetry necessary to confirm that Orion could safely house four astronauts for the duration of a multi-week lunar mission, paving the way for the return of manned lunar flight.

Artemis II: From Robotic Testing to Human Presence

The transition from the robotic testing of Artemis I to the human presence of Artemis II represents one of the most significant leaps in NASA’s recent history. While Artemis I was a solo flight for the Orion capsule and the Space Launch System (SLS), Artemis II will carry a crew of four astronauts on a high-stakes journey around the Moon and back. This mission, currently scheduled to launch as early as February, will follow a "hybrid free-return trajectory." The crew will perform multiple maneuvers in Earth orbit before committing to a translunar injection that will carry them behind the far side of the Moon, mirroring the path that provided the iconic Earthset views during the first mission.

The crew of Artemis II will be the first humans to see the Earth rise and set from the lunar perspective since the final Apollo mission in 1972. Beyond the historical significance, the mission is a critical operational test. The astronauts will manually pilot Orion during certain phases of the flight to test the spacecraft’s handling qualities and the interfaces between the crew and the onboard computers. They will also evaluate the performance of the communication systems, which must transmit high-definition video and complex data streams across hundreds of thousands of miles, ensuring that the world can share in their journey in real-time.

The Future of Lunar Exploration

The success of the Artemis II flyby is the final prerequisite for the most ambitious phase of the program: Artemis III, the mission that will return humans to the lunar surface. By proving that Orion can safely transport and sustain a crew in the deep-space environment near the Moon, NASA sets the stage for landing the first woman and the first person of color on the lunar South Pole. This region is of particular scientific interest due to the presence of water ice in permanently shadowed craters, which could potentially be harvested for life support and fuel in future "Moon-to-Mars" architectures.

Ultimately, the "Earthset" captured by Orion is more than just a photograph; it is a symbol of a new era. The psychological and scientific impact of seeing Earth from the lunar perspective—a fragile blue oasis in an infinite black void—continues to inspire the "Overview Effect," a cognitive shift reported by astronauts that emphasizes the unity and vulnerability of our home planet. As NASA moves toward the February launch window for Artemis II, the world watches as we transition from capturing images of our home from afar to sending representatives of humanity to witness those sights with their own eyes. The return to the Moon is no longer a matter of "if," but "when," as the Artemis program establishes a sustainable human presence in deep space.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!