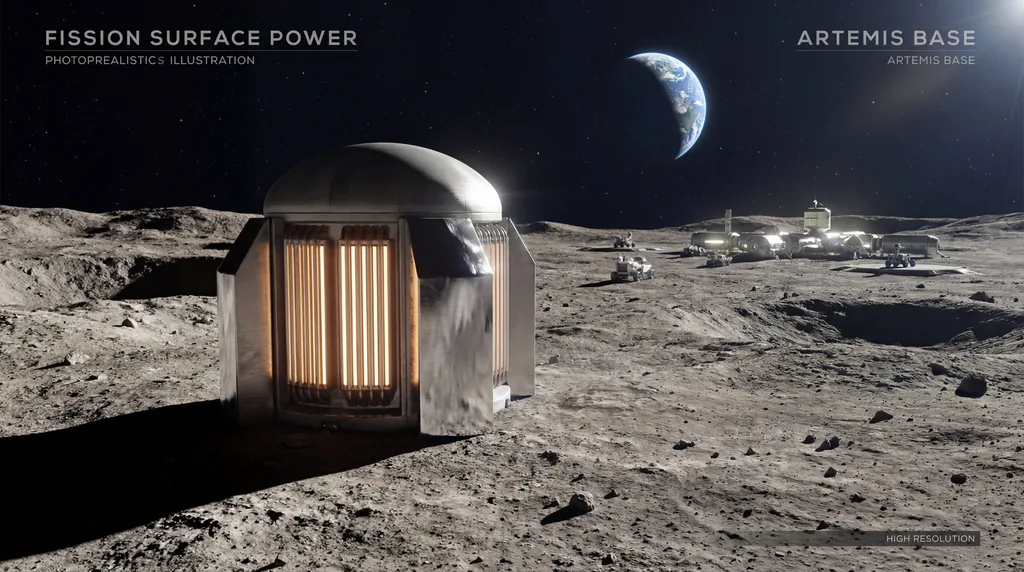

In a move that signals a paradigm shift for long-term lunar habitation, NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) have formally codified a partnership to develop nuclear fission reactors for use on the Moon. This collaboration, finalized through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) announced in mid-January 2026, aims to overcome the most significant hurdle facing the Artemis program: a continuous, high-output power supply. As the agency transitions from short-term sorties to permanent lunar infrastructure, the development of Fission Surface Power (FSP) systems has become the technological cornerstone for surviving the harsh lunar environment and eventually propelling human explorers toward Mars.

The Energy Challenge of the Lunar Surface

The lunar environment presents a unique set of challenges that traditional solar power—the mainstay of space exploration for decades—cannot fully address. A single lunar day lasts approximately 708 hours, which includes a grueling 354-hour (14-day) period of darkness. During this lunar night, temperatures plummet to nearly -173 degrees Celsius (-280 degrees Fahrenheit). Without a constant source of thermal energy, sensitive electronics and life-support systems would fail, effectively ending any mission that requires sustained human presence. Solar arrays, while efficient during the day, require massive, heavy battery storage systems to bridge the two-week gap of darkness, making them logistically prohibitive for high-power industrial applications.

Nuclear fission provides a reliable, high-density energy solution that operates independently of sunlight. According to reporting by Jeff Foust for SpaceNews, the FSP program is designed to produce a system capable of generating at least 100 kilowatts of power—enough to sustain multiple habitats and resource-extraction facilities simultaneously. Unlike solar arrays, which must be enormous to capture sufficient energy, a nuclear reactor is compact and can be placed in permanently shadowed regions, such as the lunar south pole, where water ice is believed to be trapped. This consistency is vital for maintaining thermal management, preventing the catastrophic "cold-soaking" of equipment during the long lunar night.

The NASA-DOE Strategic Partnership

The division of labor within this interagency agreement leverages the specific strengths of two of the United States' most technically advanced organizations. Under the MOU, signed by NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman and Energy Secretary Chris Wright, NASA will serve as the primary funder and program manager. The agency is responsible for defining mission requirements and providing the necessary data to ensure the reactors meet spaceflight safety standards. Conversely, the DOE will provide the technical oversight for reactor design and regulatory compliance. Crucially, the DOE is tasked with providing approximately 400 kilograms of high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU), which will fuel both the ground test units and the eventual flight reactor.

This collaboration is not without precedent; NASA and the DOE have worked together for decades on radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) for deep-space probes like Voyager and Perseverance. However, as Secretary Wright noted in a statement, this project represents "one of the greatest technical achievements in the history of nuclear energy and space exploration." The agreement streamlines the process of translating terrestrial nuclear expertise into space-rated hardware, ensuring that the FSP program remains on track for a target launch date by the end of 2029. This strategic alignment is a prerequisite for the Artemis program's broader goal of establishing a "Golden Age" of discovery.

Fission Surface Power Technology Explained

The FSP system utilizes a small nuclear reactor to generate heat, which is then converted into electricity through a power conversion system, such as a Stirling engine or a Brayton cycle turbine. In the vacuum of the lunar surface, managing heat is a critical design challenge. While the reactor generates heat to produce power, it must also shed excess waste heat through specialized radiators. The current design goals call for a 100-kilowatt class system that is robust enough to be launched on a rocket and landed on the lunar surface without compromising the integrity of its shielding or fuel containment.

The decision to utilize HALEU fuel is a significant pivot in the program’s methodology. As highlighted in the second draft of the Announcement for Partnership Proposals (AFPP) released in December 2025, NASA is now explicitly requiring the use of HALEU to align with "ongoing developments in terrestrial microreactors." HALEU contains between 5% and 20% Uranium-235, providing a higher energy density than the low-enriched uranium used in commercial power plants while remaining below the enrichment levels that trigger nuclear weapons proliferation concerns. This choice balances the need for high performance with global security standards and domestic industrial trends.

Logistics and the Human Landing System

One of the most notable shifts in NASA’s strategy involves the logistics of delivery. In previous drafts of the program's proposal call, commercial partners were expected to secure their own transportation to the Moon. However, the revised AFPP indicates that NASA will now provide launch and landing services through its Human Landing System (HLS) program. This means the reactor will likely be delivered to the lunar surface by a heavy-lift vehicle managed by either SpaceX or Blue Origin, the primary contractors for the Artemis landing missions.

This change simplifies the burden on nuclear developers, allowing them to focus strictly on reactor engineering rather than orbital mechanics and lunar descent. Proposals from industry are expected to present strategies for integrating their reactor designs directly with the HLS contractor teams. This integrated approach ensures that the reactor, which will be a heavy and sensitive payload, is handled by the same infrastructure that will deliver the next generation of astronauts to the lunar south pole, thereby reducing mission risk and streamlining the Artemis timeline.

Impact on the Artemis Program and Beyond

The implementation of nuclear power on the Moon is not merely a matter of convenience; it is the enabler for In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). To stay on the Moon sustainably, astronauts must eventually "live off the land" by extracting oxygen from lunar regolith and water from subsurface ice. These chemical extraction processes are energy-intensive and require a constant, high-output power source that solar panels cannot reliably provide at scale. A 100-kilowatt reactor would facilitate the industrial-scale processing of lunar materials, paving the way for the production of rocket propellant and breathable air.

Furthermore, the FSP program serves as a critical testbed for future crewed missions to Mars. A journey to the Red Planet involves longer durations and even more extreme environmental constraints, including dust storms that can obscure the sun for months. The technology developed for the lunar surface—compact, reliable, and durable fission reactors—will be directly scalable to Mars missions. By mastering nuclear power on the Moon, NASA is effectively building the energy foundation for humanity's expansion into the deeper solar system.

Addressing Safety, Sustainability, and Public Concern

The introduction of nuclear material into space exploration necessitates rigorous safety protocols and adherence to international treaties. NASA and the DOE have emphasized that the reactors will not be activated until they have reached their final destination on the lunar surface, ensuring that no nuclear fission occurs during the launch or transit phases. This "cold launch" strategy significantly mitigates the risk of radioactive contamination in the event of a launch failure. Additionally, the use of HALEU fuel reduces the risk of long-term environmental hazards compared to more highly enriched alternatives.

Sustainability and decommissioning are also central to the program's long-term planning. The agencies are developing procedures for the safe disposal of reactors at the end of their operational lives, likely involving "burial" in stable lunar craters or designated isolation zones. Radiation shielding for lunar astronauts is another primary focus, with designs utilizing either the lunar regolith itself or advanced synthetic materials to create a buffer between the reactor and human habitats. These measures are designed to ensure that the lunar colony remains a safe environment for scientists and explorers for decades to come.

What's Next for Fission Surface Power

As of late January 2026, the industry is currently awaiting the final version of the Announcement for Partnership Proposals (AFPP). While there have been slight delays in the release of this final call, NASA has assured potential commercial partners that they will have a 60-day window to submit their proposals once the document is published. The feedback from earlier drafts has already shaped a more collaborative and logistically sound framework, emphasizing the importance of HALEU fuel and HLS integration.

The upcoming months will be pivotal as the private sector—ranging from traditional aerospace giants to specialized nuclear startups—presents their visions for the first lunar reactor. With a target launch date of late 2029, the pressure is on to move from theoretical models to flight-ready hardware. This partnership between NASA and the DOE represents more than just a technical agreement; it is a commitment to the necessary infrastructure of the future, ensuring that when the next giant leap is taken, the lights will stay on.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!