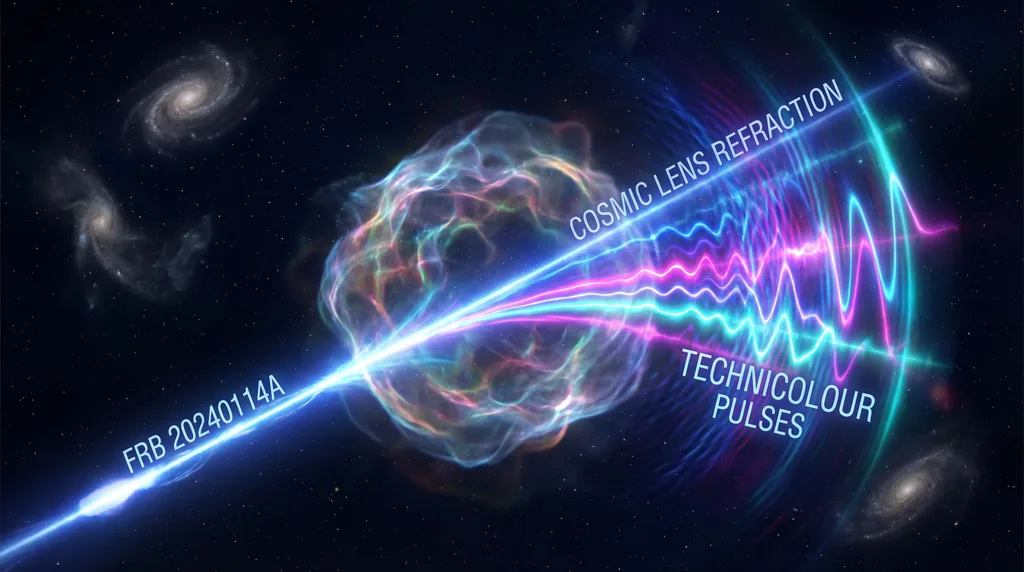

Astronomers have detected an unprecedented 5,526 bursts from a single extragalactic source known as FRB 20240114A, revealing a vivid "technicolour" display of radio emission that reshapes our understanding of the cosmos. These observations, captured using advanced ultrawideband receiving systems, provide the clearest evidence yet that massive clouds of ionized gas act as giant cosmic lenses, magnifying and distorting signals from the distant universe. By studying this highly active repeating source, a research team led by Simon C. -C. Ho, Ryan M. Shannon, and Pavan A. Uttarkar has demonstrated that the environment surrounding these mysterious objects plays a critical role in how they appear to telescopes on Earth.

Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) are millisecond-duration pulses of radio waves that originate from galaxies billions of light-years away. Since their discovery in 2007, these energetic events have puzzled scientists because of their immense power—releasing as much energy in a fraction of a second as the Sun does in several days. While most FRBs appear to be "one-offs," a small subset repeats, allowing for intensive study. The discovery of FRB 20240114A marks a turning point in the field, as its extreme activity levels provide a massive dataset that allows researchers to peel back the layers of environmental interference and see the true nature of the emission engine.

What is plasma lensing in fast radio bursts?

Plasma lensing in fast radio bursts occurs when radio photons propagate through non-uniform electron density volumes in space, causing extreme magnification or suppression of the observed flux at certain frequencies. This effect is frequency-dependent, leading to phenomena like chromatic activity, where different "colours" or frequencies of radio waves are focused more sharply than others at different times. These plasma lenses, often embedded in a turbulent medium near the source, act as a diverging or converging lens that shifts the signal's appearance as the source and observer move.

The research into FRB 20240114A utilizes this phenomenon to explain why bursts look so different even when they come from the same origin. When the radio waves pass through ionized gas—the "plasma"—the varying density of the gas bends the waves. This bending can result in "caustics," which are regions where the radio waves are concentrated into a tight, highly magnified beam. If Earth happens to pass through one of these caustics, the FRB appears significantly brighter than it actually is. Conversely, if the lens directs the waves away, the source may appear to go quiet, providing a physical explanation for the erratic duty cycles observed in many repeating sources.

What is FRB 20240114A and why is it special?

FRB 20240114A is one of the most active repeating fast radio burst sources ever recorded, providing a unique laboratory to study the physical processes of extragalactic radio emission. Unlike previous sources that showed rare repetitions, this "cyclone" of activity allowed the research team to detect over 5,500 bursts using an ultrawideband receiving system. This vast quantity of data revealed extreme spectral and temporal variability that had never been seen with such clarity, making it a "Rosetta Stone" for understanding the relationship between a source's intrinsic signal and its surrounding environment.

The study of FRB 20240114A is particularly significant because of the wide bandwidths used for observation. Traditionally, radio telescopes observe in narrow "windows," which can miss the broader context of a burst’s structure. By using an ultrawideband approach, the authors were able to track how the central emission frequency of the bursts shifted over multiple months. They discovered that while some bursts are broadband (covering a wide range of frequencies), others are narrowband and show correlations in their central frequencies on timescales ranging from milliseconds to minutes. This "technicolour" variability is a signature of the radio waves being processed by foreground plasma lenses within the host galaxy.

Can plasma lensing explain the diversity in FRB burst rates?

Plasma lensing explains the diversity in fast radio burst rates by modulating the observed flux through geometric magnification, which can make a faint source appear hyper-active or cause a frequent repeater to seem like a one-off event. This mechanism suggests that the "dichotomy" between repeating and non-repeating FRBs might be an observational illusion caused by propagation effects. If a source is situated behind a particularly turbulent plasma medium, its signals are more likely to be magnified into the detection range of our current instruments.

This discovery has profound implications for the classification of these cosmic events. Currently, the scientific community is divided on whether repeating FRBs and non-repeating FRBs are produced by different types of objects, such as magnetars or merging neutron stars. However, the evidence from FRB 20240114A suggests that many "non-repeaters" might actually be repeaters that are simply not currently being magnified by a plasma lens. By accounting for the magnification factors of plasma lenses, researchers can better estimate the true energetics and population statistics of these sources, potentially unifying the two classes into a single physical phenomenon.

The "Technicolour" Effect and Spectral Variability

The term "technicolour" refers to the complex spectral patterns observed in the 5,526 repetitions of FRB 20240114A. In these observations, the bursts did not just vary in brightness; they changed their "pitch" or frequency across the radio spectrum. Researchers noted that the central frequency of emission would drift significantly over months, a phenomenon that is difficult to explain through intrinsic source physics alone but is a natural consequence of moving through a clumpy, ionized medium. These shifts are accompanied by orthogonal polarization angle jumps, which serve as a secondary line of evidence for lensing, as different lensed paths probe different magnetic environments within the plasma.

- Broadband Variations: Long-term shifts in frequency observed over several months of monitoring.

- Narrowband Correlations: Short-term frequency stability seen in bursts occurring within minutes of each other.

- Extreme Magnification: Sudden spikes in intensity that allow even weak intrinsic pulses to be detected.

- Turbulent Medium: The presence of a "circumsource medium" that creates the lensing effect.

Implications for the Future of Radio Astronomy

Radio astronomy is currently entering a new era of "big data" where the volume of detected events is outstripping our ability to manually categorize them. The findings regarding FRB 20240114A highlight the necessity of ultrawideband receivers and high-cadence monitoring to truly understand the transient sky. As we build more sensitive telescopes, such as the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), the role of the intervening ionized gas will become a primary focus of study, not just as a nuisance to be filtered out, but as a tool to map the "hidden" matter in the universe.

Looking forward, the research team suggests that studying the "lensing cycles" of sources like FRB 20240114A could allow astronomers to map the structure of distant galaxies in unprecedented detail. Because the lensing depends on the density of electrons, these bursts act as a backlight that illuminates the otherwise invisible gas between stars. Future directions will involve looking for similar "technicolour" signatures in other repeating sources to determine if plasma lensing is a universal feature of the FRB population or a unique characteristic of certain galactic environments.

In conclusion, the study of FRB 20240114A by Simon C. -C. Ho and colleagues demonstrates that the universe's most energetic whispers are being amplified by cosmic mirrors. This discovery not only provides a solution to the mystery of FRB variability but also gives us a new way to probe the ionized medium of the deep universe. As we continue to monitor this "technicolour" source, we move one step closer to identifying the physical engines—perhaps highly magnetized neutron stars—that drive these extraordinary cosmic explosions.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!