This week, as researchers reanalyse half-a-century of archived measurements, scientists revisit Viking data and argue that the first probes to touch Martian soil may have recorded biological activity in 1976 — then destroyed the evidence during their own analyses. Viking 1 and Viking 2 carried three dedicated life-detection experiments and a tiny gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer (GC‑MS); contemporary teams recorded puzzling gas releases that some investigators said looked like metabolism even while the GC‑MS reported no clear organics. New laboratory simulations, a reexamination of the experimental records, and the later discovery of reactive salts on Mars have combined to reopen a debate long closed by NASA's original interpretation.

Scientists revisit Viking data: what the experiments actually did

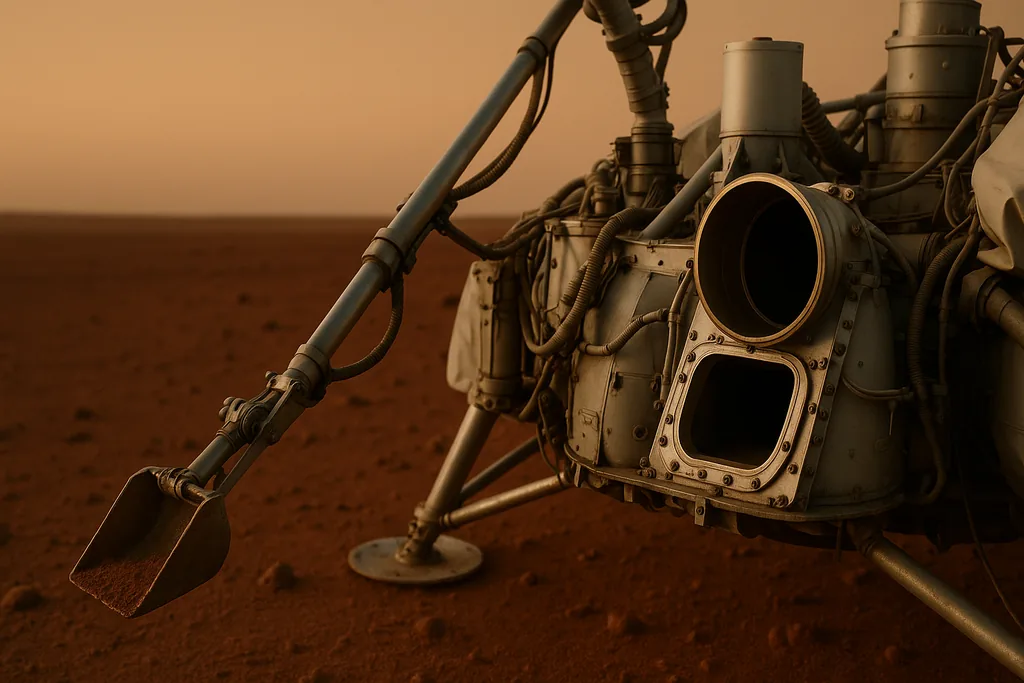

The Viking landers each carried a miniaturised biology lab that ran three complementary tests designed to be decisive. The Labeled Release (LR) experiment injected dilute, radioactively labelled nutrients into soil samples and monitored the atmosphere above for radiolabel‑bearing gases that would indicate metabolism. The Gas Exchange (GEx) experiment moistened soil and watched for changes in O2, CO2 and other gases, testing whether the ground produced or consumed common metabolic gases. The Pyrolytic (Pyrolytic/Pyrolytic Release, PR) experiment exposed soil to a mixture of light and simple gases to see whether carbon fixation occurred. In parallel, a GC‑MS heated small soil aliquots and scanned for organic molecules.

Several of those biology tests produced active responses. The LR readings, in particular, showed prompt release of radiolabelled CO2 in many samples — a pattern that the LR principal investigator, Gil Levin, and others interpreted as consistent with microbial respiration. The GEx returned transient oxygen variations when samples were wetted that some scientists saw as biologically plausible. But the GC‑MS runs, which derived volatile fragments by heating the soil, failed to find unambiguous complex organics; they reported CO2 and trace chlorinated hydrocarbons. At the time, NASA's working judgement was to consider the GC‑MS result decisive and to treat the positive biology tests as the product of unfamiliar, abiotic chemistry in a strange, oxidising regolith.

Scientists revisit Viking data: perchlorate and the problem of destructive tests

The single most important new fact to enter the conversation after Viking was the Phoenix lander's 2008 discovery of perchlorate salts in Martian soil. Laboratory studies since then, including work led by Rafael Navarro‑González and collaborators, showed that perchlorates are strong oxidants when heated and will react with organic matter to produce chlorinated methane species and CO2 — precisely the signatures Viking's GC‑MS observed. Those chloromethanes had been dismissed in 1976 as terrestrial contamination, but the later chemistry suggests they could instead be the breakdown products of native organics that the GC‑MS ovens incinerated.

Put bluntly: the thermal step that enabled chemical analysis on Viking may have simultaneously erased the molecular evidence that would have confirmed the biological signals. Simulations show even modest perchlorate fractions can fragment or combust organics during pyrolysis. That mechanism reconciles the paradox at the heart of the original controversy: why did the LR and other biology experiments look alive while the GC‑MS reported an absence of organics? The new reading is that organics were present but destroyed by the analytical method.

Reinterpreting positive signals and the BARSOOM model

Some investigators have gone further than attributing GC‑MS failure to perchlorate chemistry. Chemist Steve Benner and colleagues have proposed mechanistic models — sometimes summarised under acronyms such as BARSOOM in recent commentary — that describe plausible Martian microbes that could explain the pattern of observed responses. These hypothetical organisms would be highly adapted to cold, dry, oxidising conditions, perhaps using bound oxygen or unconventional metabolic pathways that release trace gases when supplied with liquid nutrients.

Proponents argue this biological account explains multiple lines of Viking evidence in a single framework: the LR's rapid radiolabel uptake, the GEx oxygen dynamics, and the particular chlorinated breakdown products in GC‑MS runs are all consistent with microbes that were briefly activated by the landers' wetting or nutrient pulses and then consumed by heat during chemical analysis. Critics caution that models remain speculative: they can fit the data but do not replace direct chemical detection of complex organic molecules. The debate now focuses not on whether a clever model can be made to fit, but on producing reproducible, testable predictions and fresh laboratory experiments under Mars‑like conditions.

Why scientists revisit Viking data now and what it means for consensus

Part of the renewed attention is historical — the Viking landings are approaching their 50th anniversary and archived datasets have been digitised, which invites fresh analysis with modern knowledge. More importantly, new empirical facts (perchlorate, seasonal methane detections, and the consistent discovery of organics by Curiosity and Perseverance in protected rocks) make the old interpretation look less secure. The current consensus in astrobiology is cautious: the Viking experiments produced intriguing, unexplained signals, and the absence of detected organics in 1976 no longer settles the question.

That caveat matters. Scientific consensus today is not that Viking proved life existed on Mars, but that Viking's negative verdict deserves reassessment. Many researchers say the LR's positive readouts and subsequent chemistry require a renewed, methodical effort to test whether those patterns can be produced by abiotic soil chemistry under realistic Martian conditions, or whether biology remains the simplest explanation. The result is that the community has moved from a settled 'no' toward a nuanced 'inconclusive, but reopened'.

Implications for current and future missions

The Viking reanalysis has practical consequences for mission design and planetary protection. Modern rovers avoid destructive heating as a first step: Perseverance uses non‑destructive spectroscopy, imaging, and carefully sealed caching to preserve samples for eventual return to Earth, where full‑scale laboratories can apply sensitive wet chemistry and avoid perchlorate artefacts. Mars Sample Return, now a flagship objective, is explicitly motivated by the limitations that hampered Viking — the goal being to deliver pristine samples to terrestrial labs with far greater analytical flexibility.

There is also an ethical and policy angle. If it remains plausible that Viking might have contacted living organisms, even transiently, the design of future spacecraft and any human missions must weigh the risk of forward contamination — accidentally introducing Earth microbes to fragile Martian ecosystems — and backward contamination. Planetary protection rules already incorporate conservative safeguards, but the renewed debate strengthens the argument for rigorous containment, sterilisation protocols, and careful site selection before human footprints are allowed.

How the Viking story answers long-standing questions

Did Viking detect microbial life on Mars? The short, careful answer is: the experiments produced signals consistent with microbial activity, but the mission's chemical analyses did not provide corroborating molecular evidence, and NASA's official conclusion has been 'no life' based on that balance. What evidence suggested microbial life? The LR's radiolabelled gas release and the GEx oxygen responses were the most evocative data points; they behaved in ways that on Earth would be treated as metabolic. Why are scientists revisiting Viking data? Because perchlorate and other discoveries, plus lab work showing high‑temperature analyses can destroy organics, mean the original negative GC‑MS result may have been a false negative. How did the Viking experiments work and what did they find? They combined wetting and nutrient additions, light‑exposure tests, and thermal chemical scans — a complementary suite that produced some positive biological signatures and some ambiguous chemical signatures. What is the current consensus? It is not a settled acceptance of life on Mars but a reopened question: the evidence is reinterpretable, and resolving it now rests on new samples and better analytical control.

As the field moves on, the Viking story is a reminder that method matters: the right question answered with the wrong method can erase the answer entirely. For astrobiology, the next decade — with Mars Sample Return, continued rover campaigns, and rigorous laboratory simulations — will be decisive in determining whether those first signals were the first hint of life beyond Earth or a particularly deceptive chemistry of an alien soil.

Sources

- NASA – Viking mission experimental data and archives

- NASA – Phoenix mission findings on perchlorate

- Rafael Navarro‑González (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) laboratory studies on perchlorate and organics

- Steve Benner / Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution (research and modelling commentary)

- NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory – Perseverance and Mars Sample Return mission documentation

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!