In the lab: a tangible step toward a universal organ

This week researchers published results showing a precise biochemical trick that moves us closer to the long‑sought promise captured in the phrase breakthrough: scientists created 'universal'. Teams led from the University of British Columbia and collaborators used lab‑grown enzymes to strip the sugar markers that define blood type A from a donor kidney, converting it to an enzyme‑converted type O organ and implanting it into a brain‑dead recipient with family consent. The organ worked for several days with only limited immune trouble, giving clinicians and scientists their first human model of an organ made broadly compatible with any blood type.

The finding was reported in Nature Biomedical Engineering in 2025 and is the result of more than a decade of incremental work on enzymes that can cut specific carbohydrate structures off cell surfaces. For patients waiting for transplants—many of whom must wait years because their blood type limits compatible donors—the idea of a kidney that can match any blood type is more than a laboratory curiosity: it is a potential pathway to dramatically reduce waiting lists and deaths on them.

breakthrough: scientists created 'universal' kidney — how the enzyme trick works

Researchers adapted enzymes discovered and optimised in earlier studies that act like molecular scissors: they specifically remove the terminal sugars that make type A or B antigens visible. Remove those sugars and the organ's blood‑vessel surface behaves, for a time, like type O—which is functionally the universal type because most people's immune systems do not mount anti‑O responses.

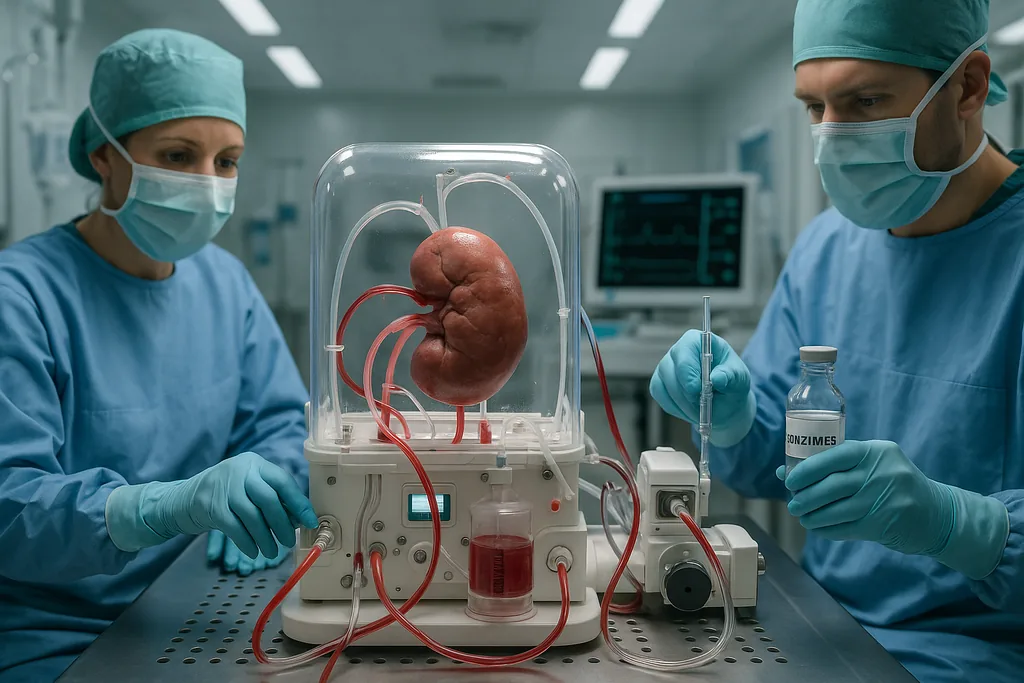

In practical terms, the team perfused a donor kidney with a cocktail containing those enzymes ex vivo, creating an enzyme‑converted organ (often abbreviated ECO). Laboratory and preclinical tests had shown the approach could work for blood (where the enzymes had first been trialled) and for isolated organs. The new work extended that to an organ transplanted into a human body, albeit one without brain function, to observe compatibility and early immune reactions.

breakthrough: scientists created 'universal' kidney — the first human test and what happened

The converted kidney was transplanted into a brain‑dead recipient with full family consent so researchers could monitor how the organ behaved in a living circulation. For roughly two days the kidney functioned without hyperacute rejection—the catastrophic immune reaction that can destroy a mismatched graft within minutes. That alone represents a meaningful milestone: a converted organ survived initial exposure to a fully intact human immune system.

Translating the lab result into usable transplants

So what is a universal kidney and how does it work in everyday clinical language? In this context a "universal kidney" is a donor organ whose surface antigens have been chemically or enzymatically modified so that the organ no longer carries the blood‑group markers that would trigger immediate antibody‑mediated rejection. It works by replacing the donor's visible cellular "nametag" with a neutral surface, effectively broadening the pool of recipients who could accept that organ without prolonged matching or dangerous preconditioning.

Risks, ethics and the road to clinical trials

Are universal organs available for transplant today? No. The human transplant was a controlled research step, not a clinical offering. Before any routine clinical use the technique must clear regulatory reviews, safety testing and larger clinical trials. The company spun out of the research—Avivo Biomedical—is preparing to seek approvals and run trials, but those processes typically take years. Researchers emphasise that this is a bridge between strong laboratory evidence and eventual patient care, not the endpoint.

The short‑term risks are immune reactions once antigens re‑emerge, unforeseen side effects of the enzyme treatment on vascular cells, and potential influences on long‑term graft health. There are ethical considerations too: the first human test relied on a brain‑dead donor with family consent, a necessary but sensitive design that provided the chance to monitor the organ in a living circulation without placing an active patient at immediate risk.

Longer term, teams must show the conversion is durable enough to meaningfully improve outcomes and that any reduction in matching constraints does not create new vulnerabilities—such as hidden antigenic changes or increased susceptibility to infection. Regulators will want carefully staged human trials that measure short‑ and long‑term rejection rates, function, and safety across diverse recipients.

System‑level impact and when could this help patients?

If the approach survives trials, it could change organ allocation and reduce inequities. Type O recipients currently dominate many kidney waitlists and wait longer because true type O donor organs are scarce; converting A or B kidneys to functional O could increase available organs and shorten waits. But realistic timelines put broad clinical availability years away rather than months. Researchers and company partners describe a path that, if everything goes well, leads to phased clinical trials within a few years followed by larger efficacy studies and regulatory review.

The risk‑benefit calculus for an individual patient will depend on their medical condition and the alternative options available. For many, earlier access to a functioning transplant—if it can be shown safe—would far outweigh some uncertainties. For clinicians and transplant services, the technique could loosen the tight choreography currently needed to pair donors and recipients while also easing pressure on living donation programmes.

What remains to be solved

- Durability: preventing antigen reappearance or controlling it over clinically relevant timeframes.

- Immunology: assessing how non‑ABO immune mechanisms interact with converted grafts.

- Manufacturing and logistics: scaling enzyme production and building protocols for safe, rapid organ conversion before transplant.

- Ethics and access: ensuring equitable deployment so benefits reach those who need them most.

The headline captures a promising milestone: breakthrough: scientists created 'universal' organs isn't hyperbole yet, but a succinct description of a powerful idea now demonstrated in human physiology for the first time. The conversion technique answers a clear scientific question—how to make a kidney match any blood type—while opening a longer, practical conversation about safety, regulation and equitable rollout. If subsequent trials confirm durable benefit, the change could be profound for people who die waiting for a kidney every year.

Sources

- Nature Biomedical Engineering (research paper on enzyme‑converted organs)

- University of British Columbia (research teams and press materials)

- Avivo Biomedical (company developing clinical translation)

- Centre for Blood Research, University of British Columbia

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!