Three labs, three approaches, one goal: untether the brain

In papers published between November and December 2025, research teams at Cornell, Columbia/Stanford/UPenn, and MIT described three very different routes toward wireless, minimally invasive brain interfaces. At Cornell and Nanyang Technological University researchers revealed MOTE, a microscale optoelectronic device that is literally smaller than a grain of salt and recorded neural spikes in mice for more than a year. At Columbia and its clinical collaborators, engineers unveiled BISC, a paper-thin silicon implant that packs tens of thousands of electrodes and a 100-megabit wireless link. And at MIT, scientists presented "circulatronics": cell–electronics hybrids that can travel through the bloodstream, cross the intact blood–brain barrier and self‑implant at a target site to provide focused electrical stimulation. Each project tackles a different bottleneck — size, bandwidth, or surgical risk — and together they illustrate how diverse the technical choices are when you try to put electronics next to neurons.

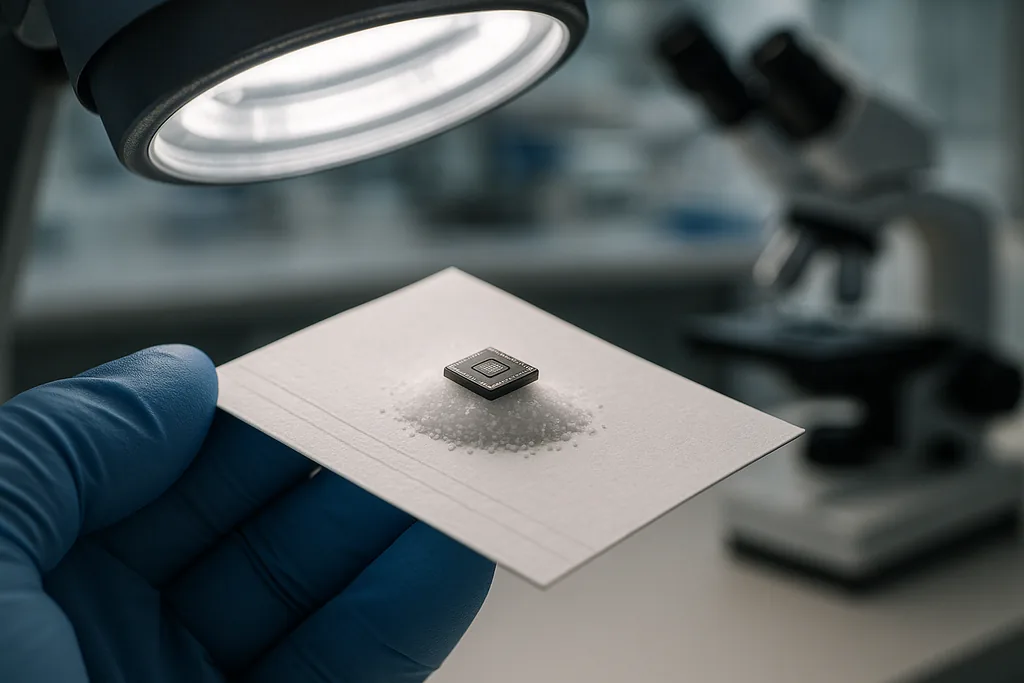

Extremes of miniaturisation: the MOTE

In laboratory tests the device was placed on or injected into the mouse barrel cortex and recorded both single‑neuron spikes and broader synaptic activity reliably over the course of a year while producing minimal scarring. The team applied atomically thin protective coatings during fabrication to slow corrosion in the brain’s fluid environment, and they note the device’s materials may be compatible with MRI — a meaningful practical advantage for future clinical work. The MOTE paper appeared in Nature Electronics and is important because it demonstrates chronic, tetherless recording at a scale much smaller than previously thought feasible.

High‑bandwidth, paper‑thin cortical chips: the BISC platform

The single‑chip BISC design contains 65,536 electrodes, 1,024 recording channels and more than 16,000 stimulation channels, plus on‑chip radios and power management. In published tests the system demonstrated a relay station that bridges the implant to external computers with an ultrawideband radio link capable of around 100 Mbps — orders of magnitude greater throughput than most wireless BCIs today. That bandwidth is what makes BISC attractive for clinical neuroprosthetics and for linking cortical population activity to machine learning decoders. The implant was fabricated using established semiconductor foundry processes and the team has already begun short intraoperative human studies and spun out a startup to commercialise the device.

Non‑surgical delivery: MIT’s circulatronics

The researchers tested circulatronics in mice and showed targeting to inflamed brain regions and local stimulation with micron‑scale precision, while avoiding the tissue damage and immune attack that plague larger implants. The work appeared in Nature Biotechnology and charts a possible nonsurgical route to millions of microscopic stimulation sites, with obvious implications for treating focal inflammation, glioblastoma or diffuse lesions that are hard to reach surgically.

Power, communication and the immune system: trade‑offs that define the field

When you compare the three platforms, the differences reduce to a few core engineering trade‑offs. Power and telemetry dominate design: MOTE uses transmitted light for both energy and optical outbound signalling, allowing tiny size at the cost of limited data rate and depth penetration. BISC uses on‑chip radios and an external relay to achieve very high data throughput and integrated stimulation, but it requires placement in the subdural space and a wearable relay. Circulatronics sidesteps surgery entirely by piggybacking on cells to transport electronics, but that requires careful biological engineering to control where devices go and how they behave once they arrive.

Biocompatibility is another axis. The brain’s fluids corrode electronics and provoke immune responses; teams use different countermeasures — atomic‑layer protective coatings for MOTE, flexible conformal substrates for BISC and living‑cell camouflage for circulatronics. Each strategy brings new uncertainties: tiny devices that escape tracking, long‑term fate of injected hybrids, or unexpected interactions with imaging modalities and other medical devices.

Clinical pathways, commercialisation and regulatory hurdles

All three projects are explicitly translational but face different regulatory and commercial challenges. BISC’s use of established semiconductor manufacturing and its subdural surgical insertion map naturally to existing implant regulation and neurosurgical workflows, which helps move it toward clinical trials. Cornell’s MOTE is many steps further from human use: chronic mouse recordings are encouraging but scaling optical powering and data collection across human skull thicknesses remains a technical hurdle. MIT’s circulatronics concept is the most disruptive of the three from a clinical perspective — eliminating craniotomy in favour of an injectable route — but it will also attract the most regulatory scrutiny because it deliberately crosses the blood–brain barrier and uses living cells as transport.

Commercial activity is already underway: Columbia/Stanford researchers have launched a company to make BISC research kits, and the MIT team has plans to move toward trials through a startup. Funding sources include the US National Institutes of Health and, in some cases, defence‑sourced programmes that have long supported high‑risk neural engineering work. That mix speeds research but reopens questions about dual‑use and governance for powerful brain‑computer technologies.

Ethics, security and what “wireless” really means for the mind

As implants grow smaller and wireless links grow faster, the ethical issues shift from surgical risk to questions of privacy, data ownership and control. High‑bandwidth devices like BISC bring the potential to record, decode and stimulate with high temporal and spatial resolution — capabilities that raise hard questions about who can access neural data, how it is stored and analysed, and how to prevent unwanted interference. Miniature implants like MOTE or self‑delivering circulatronics challenge regulatory frameworks that assume devices are physically traceable and removable. Researchers and clinicians emphasise therapeutic goals — epilepsy control, paralysis recovery, visual restoration — but engineers and ethicists are already urging parallel work on standards for security, informed consent, and long‑term follow‑up.

A plural future for neural interfaces

What emerges from these papers is not a single winner but a toolkit. For some applications — high‑performance prosthetic control or research-grade cortical mapping — a high‑bandwidth, wafer‑scale chip like BISC looks most promising. For minimally invasive monitoring or interfacing with organoids and small neural structures, MOTE‑style optical microdevices could open experiments that were previously impossible. And for therapeutic neuromodulation where surgery is impractical, cell‑delivered circulatronics hint at a radical alternative.

Those possibilities are exciting, but translating them into safe, equitable clinical technologies will take years of engineering, long‑term animal and human studies, regulatory work, and public conversation about acceptable uses. The near future of brain implants is therefore not a single miniature miracle but an expanding set of trade‑offs that clinicians, regulators and society will have to weigh carefully.

Sources

- Nature Electronics (research papers on MOTE and BISC)

- Nature Biotechnology (research paper on circulatronics)

- Cornell University (Molnar lab, Cornell NanoScale Facility)

- Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Science (BISC collaboration)

- MIT Media Lab / Nano‑Cybernetic Biotrek Lab (circulatronics research)

- DARPA Neural Engineering System Design program