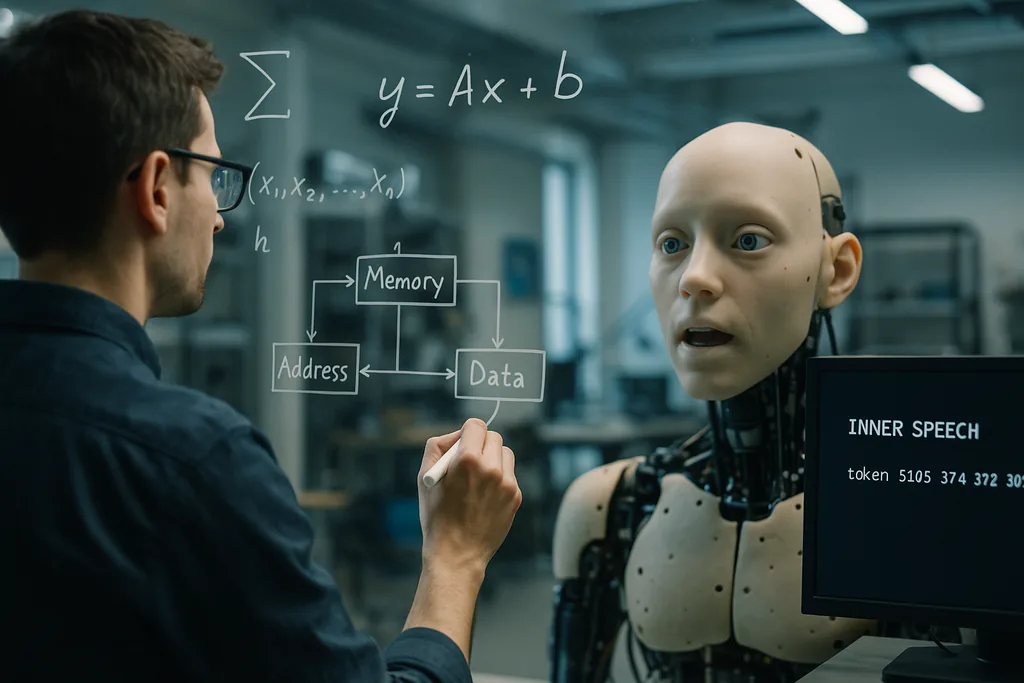

A lab that taught machines to mumble

This week, researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) reported a simple but striking idea: artificial agents learn to generalize better when they are trained to "talk to themselves." Published 22 December 2025 in the journal Neural Computation, the study shows that adding a self-directed verbal rehearsal signal — the team describes it as a kind of programmed "inner speech" or self-mumbling — together with a working-memory architecture that gives the model multiple short-term memory slots, improves performance on hard tasks that require multitasking and stepwise pattern generation.

How the experiment was built

The researchers ran computational simulations using active inference frameworks. They compared several architectures for short-term memory and tested whether adding a target that required the agent to emit internal tokens — effectively forcing the model to "mumble" to itself a specified number of times — changed learning outcomes. Systems with multiple temporary memory slots outperformed simpler memory schemes on transfer and multitasking. Crucially, when inner-speech targets were layered on top of that memory structure, task-switching and multistep sequence completion improved further.

OIST frames the method as content-agnostic: the inner speech does not need to be semantically meaningful in human terms, but acts as a rehearsal and control signal that structures internal dynamics. That made the approach particularly valuable in low-data regimes where standard deep-learning models typically struggle to generalize beyond their training examples.

Why saying things out loud — to yourself — helps

There are two complementary intuitions behind the effect. First, short-term memory slots give the system temporary containers for intermediate results and instructions, letting it hold multiple pieces of transient information while a longer computation proceeds. Second, the inner-speech signal provides an internal scaffold: rehearsing or re-encoding intermediate steps helps the learner maintain and reuse information when switching tasks or when a sequence contains many steps.

From a machine-learning perspective, this can be seen as adding structure to the agent's internal state-space so it can move through computation in a staged, repeatable way. The researchers argue that this kind of structured self-interaction is an inexpensive alternative to giant training datasets or brute-force model scaling for achieving flexibility.

Mathematical echoes in unexpected places

Two other recent research threads help place OIST's results in a wider conceptual frame. At the University of Pennsylvania, engineers showed that the internal reorganization of bubbles in foams follows mathematics that mirrors how modern deep networks navigate their training landscapes. Where older metaphors treated bubbles as getting trapped in valleys like glass, new analyses see both foams and trained AI parameters meandering within broad, flat regions rather than sinking into narrow optima. That continuous reorganization is what lets models generalize: staying in flatter parts of the landscape makes solutions robust to new inputs.

Read together, the studies suggest a common mathematical intuition: systems that maintain flexible, rehearseable internal dynamics — whether bubbles in a physical material or variables inside a neural controller — avoid brittle overfitting and remain adaptable. OIST's inner speech could be one practical mechanism by which an AI keeps its internal trajectory in those broader, generalizable valleys.

Embodiment and social signals: links to robotics and affective AI

Inner speech sits naturally alongside these trends. An embodied agent that rehearses internal steps — a robot that not only models the external world but also maintains and vocalizes a short internal plan — could better coordinate motor sequences (lip-syncing or manipulation), interpret human partners' cues, and explain its own decisions in human-friendly terms. That layering of internal self-models with external perception is also central to efforts aiming to make AI reliable outside narrow training distributions, such as projects seeking robust human-in-the-loop R&D and machines that reason about experts' tacit objectives.

Promises and limits

The OIST results are promising but preliminary. The experiments reported are computational simulations; models still need to be validated in noisy, dynamic, real-world environments where sensors fail, delays occur, and goals change unpredictably. The team openly recognizes this, saying their next steps will ‘‘make things messier’’ to mimic developmental learning in the wild. Embodied trials with robots in household or agricultural settings will be the real test of whether inner speech scales from simulated tokens to robust physical behaviour.

There are also conceptual and ethical considerations. Scientists must avoid anthropomorphic shorthand: a model's "inner speech" is not subjective thought; it's an engineered rehearsal signal. Still, the label matters for public perception. Systems that produce self-directed language or that narrate internal steps could be mistaken for conscious agents. That raises requirements for transparency: designers should clearly document what an internal speech channel does, how it can fail, and whether it can be coerced or manipulated by adversarial inputs.

Why it matters

If inner speech and lightweight working-memory architectures reliably improve generalization and multitasking with modest data, the practical implications are broad. AI systems that need to adapt on the fly — household robots juggling tasks, agricultural drones responding to changing crops, or lab assistants working with scarce experimental data — could become more efficient, safer, and more useful without exponential growth in labelled training sets. Moreover, the idea dovetails with mathematical and embodied-learning perspectives now emerging in materials science and robotics, suggesting fertile cross-disciplinary paths.

What started as a cognitive-inspired trick — teach the machine to rehearse — may therefore point to a deeper engineering principle: build internal structure that lets agents reorganize flexibly rather than overoptimise rigidly. If future experiments in real environments confirm the simulations, "talking to yourself" may become a standard tool in the architecture toolkit for robust, human-aware AI.

Sources

- Neural Computation (research paper: Working Memory and Self-Directed Inner Speech Enhance Multitask Generalization in Active Inference)

- Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) press materials

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (foam study on slow relaxation and landscape-driven dynamics in viscous ripening foams)

- University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science

- Science Robotics (robot lip-syncing research)

- Columbia Engineering (Creative Machines Lab)

- Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST) — multimodal social-signal research

- ELLIS Institute Finland / Aalto University (research on human-AI teams and out-of-distribution robustness)