Ancient coordinates, modern X-rays

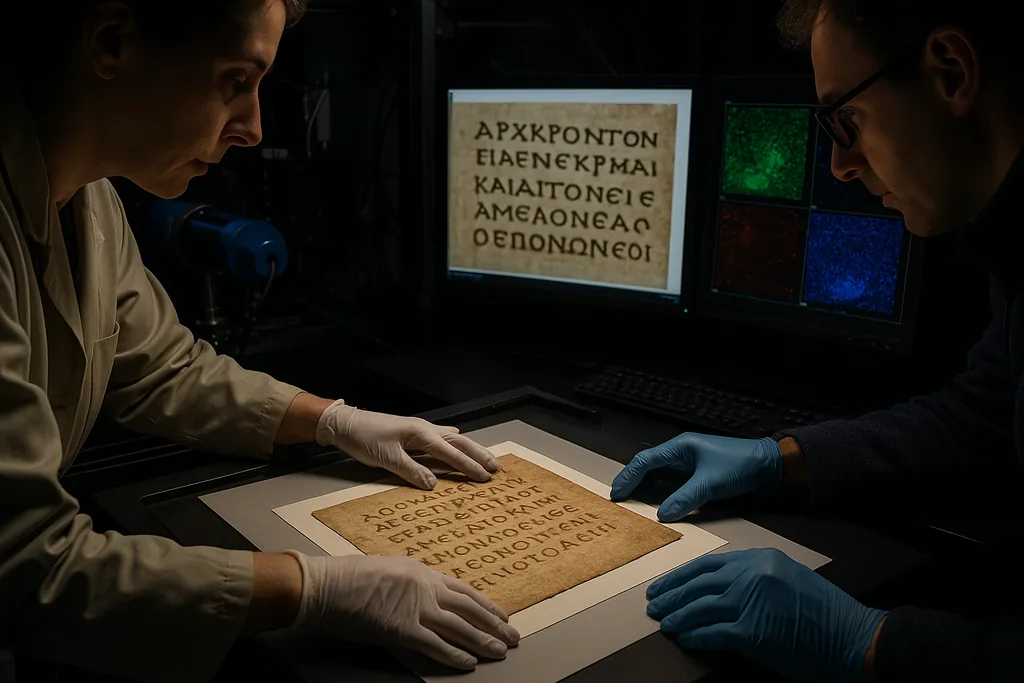

Under dim lights in a laboratory at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory this week, monitors began to show letters that had not been seen for centuries: crisp lines of ancient Greek emerging from beneath a later Syriac religious text. The pages — part of the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, a medieval palimpsest — contain numerical star coordinates that scholars now identify as work by Hipparchus, the 2nd-century B.C. astronomer often called the father of observational astronomy. The images were produced on and around Jan. 21, 2026, by scientists using the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource and a suite of X-ray fluorescence techniques.

Why a palimpsest hides a sky map

A palimpsest is a manuscript in which an older text was scraped away and overwritten because animal-skin parchment was expensive. In this case, monks at Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai recycled pages centuries after Hipparchus's time, writing a Syriac translation of St. John Climacus over the earlier Greek notes. To the naked eye the religious text is visible; the underlying Greek had long appeared as faint smudges — enough to tease scholars but not enough to read.

Synchrotron light as a humanities tool

At SLAC, an interdisciplinary team engineered a scanning system that fires hair-width X-ray pulses — each only a few milliseconds long — across the fragile folios. The synchrotron accelerates electrons nearly to light speed; as magnets bend their paths the electrons emit extremely bright X-rays, which are then focused on the manuscript. Detectors measure the fluorescent X-rays emitted by specific elements in the inks, producing a high-resolution map of where iron, calcium and other elements sit on the page.

Multispectral imaging had previously pulled fragments of the invisible text into view, but the resolution and elemental sensitivity available at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource allow the team to resolve entire lines and, in many cases, the numbers that make up star coordinates. Because X-rays penetrate both sides of the parchment, researchers also run advanced statistical algorithms to disentangle overlapping inscriptions; on some pages the group has to separate as many as six layers of writing.

The people and precautions behind the scans

Pulling off the experiment required conservators, physicists and classicists working in close coordination. Conservator Elizabeth Hayslett prepared and hand-carried 11 folios from the Museum of the Bible in controlled humidity cases to Menlo Park. Custom matting and frames kept pages flat beneath the X-ray beam; lights were kept low to avoid further fading. Researchers deliberately kept the X-ray dose well below levels used in many conservation scans — comparable to a medical X-ray — and each pulse hit only a microscopic area to minimise cumulative exposure.

Sam Webb, who built much of the scanning hutch, called the operation "a massive interdisciplinary feat." Victor Gysembergh, the lead scholar on the project, said the early results already show words such as the Greek name for the constellation Aquarius and descriptions of particularly bright stars.

What the coordinates could change

Hipparchus is credited with compiling one of the earliest systematic catalogs of stellar positions. For more than a century historians have debated how Hipparchus’s observations relate to Ptolemy’s later star listings: was Ptolemy copying Hipparchus wholesale, adapting prior material, or combining multiple sources? The newly recovered coordinates allow direct comparison between Hipparchus’s own positions and Ptolemy’s published catalog. Gysembergh says early comparisons indicate that Ptolemy sometimes used Hipparchus’s data but also integrated other material — a pattern the team describes as scientific synthesis rather than simple plagiarism.

Beyond attribution, the scans promise to quantify how accurately naked-eye astronomers could measure positions two thousand years ago. The recovered coordinates appear, so far, to show an impressive precision for observations made without telescopes; analyzing the methods Hipparchus used may change historians' views of ancient measurement practice and the speed at which early Greek science developed.

Digital disentangling and slow scholarship

Reading the catalog is still a multi-stage process. Physicists and imaging scientists generate elemental maps; software engineers and Ph.D. students statistically separate front- and back-side contributions and disentangle multiple overwrites. Then philologists and classical scholars will undertake meticulous transcription and translation of the Greek numerals and annotations. Only after that will the coordinates be placed on modern sky charts to test precision and identity.

Keith Knox, an imaging scientist with the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library who worked on the Archimedes Palimpsest, said the project extends a decades-long trajectory of applying modern instruments to recover lost texts. The team hopes demonstrating the power of synchrotron X-ray fluorescence will encourage other collections and museums to bring fragile, overwritten manuscripts to facilities with similar capabilities.

Wider manuscript network and next steps

The 11 pages scanned at SLAC are part of a larger codex that runs to about 200 pages; other leaves are scattered across institutions worldwide. The Museum of the Bible provided the folios scanned in California, but the Codex Climaci Rescriptus exists in fragments in multiple collections. The project’s next phases include scanning additional folios, expanding the set of pages available to classicists, and publishing a critical edition of the recovered catalog once translations are complete.

For now, the visible lines of Greek in the SLAC lab are a sharp reminder that a physical object produced in antiquity can still change modern scholarship — when viewed through the right light. As Gysembergh put it, the team is trying to "recover as many of these coordinates as possible" to answer deep questions about how and why people began doing systematic science more than two millennia ago.

Sources

- SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource)

- Museum of the Bible

- Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai

- Early Manuscripts Electronic Library