A new, startling close-up of a galaxy’s hungry heart

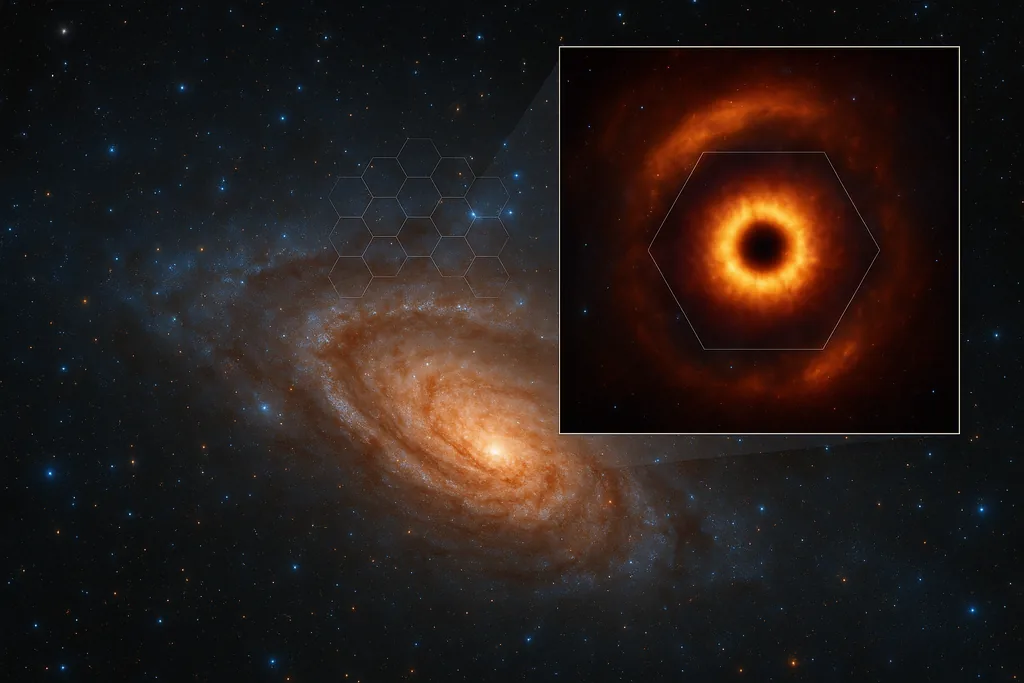

On 13 January 2026, a team using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) published an image that for the first time resolves the immediate dusty environment around a nearby supermassive black hole with interferometric clarity. The target, the Circinus galaxy about 13 million light-years away, has long frustrated astronomers because its nucleus shows an unexplained excess of infrared light. Webb’s near-infrared aperture-masking observations show that the majority of that glow comes from the inner face of a compact, doughnut-shaped dusty disk feeding the black hole — rather than from hot winds blasting material away. This sharp, space-based interferometric view promises to settle a decades-old debate about where active galactic nuclei hide their infrared light and how black holes interact with their host galaxies.

Aperture masking: turning Webb into a bigger telescope

The result depends on an unusual observing trick. JWST’s NIRISS instrument contains an aperture-masking interferometer (AMI) — a physical mask with seven hexagonal holes placed over the telescope’s pupil. By turning Webb into a small interferometer, AMI recovers information on scales about twice finer than the telescope’s nominal diffraction limit, effectively giving a spatial resolution equivalent to a roughly 13‑metre telescope for these measurements. That gain in sharpness let the team isolate structures only a few parsecs across at the galaxy’s centre and separate emission from the torus, the accretion disk and any outflowing material. The technique was used on two visits to Circinus in July 2024 and March 2025 to build the dataset.

What the image actually shows

At the scales Webb probed — roughly a 33‑light‑year region around the nucleus — the new analysis finds that about 87% of the mid‑infrared excess light arises from the inner face of the torus: a compact, equatorial dusty disk that is heated as it funnels material toward the central engine. Less than 1% of the measured infrared flux can be attributed to hot dust in outflowing winds, while the remaining fraction comes from more extended dust heated by the active nucleus or associated radio structures. In other words, the dominant infrared fingerprint in Circinus is accretion, not ejecta. That balance is the key to understanding how the black hole feeds and how much energy it returns to its surroundings.

Why this resolves a long‑standing infrared mystery

For years, observers had detected an infrared ‘excess’ around some active galactic nuclei (AGN) — more emission than simple accretion‑disk models predicted. Ground‑based interferometers and space telescopes lacked the combination of sensitivity and contrast needed to separate competing sources of that light in dusty, crowded galactic centres. Competing explanations invoked hot dusty winds launched by the black hole, scattered starlight from the galaxy bulge, or emission from the inner torus. Webb’s interferometric image breaks that tie in Circinus by showing directly where the light originates, and therefore which physical processes dominate in this object. That matters because whether an AGN’s light comes from outflows or from a compact feeding structure tells you whether the black hole is primarily redistributing gas (which can suppress star formation) or quietly accreting material without blasting its host apart.

Implications for galaxy evolution and AGN feedback

Black holes and galaxies grow together, but the coupling mechanism — how black holes heat, expel or otherwise control the gas that forms stars — remains a central uncertainty in astrophysics. If many nearby AGN resemble Circinus, with most nuclear infrared emission coming from compact dusty disks, then models that attribute significant galactic-scale feedback to sustained, dust‑entrained winds may need revision for moderate‑luminosity nuclei. Conversely, brighter AGN might still be wind‑dominated; the Webb team explicitly warns that Circinus is only one data point and that intrinsic luminosity and geometry will change the outcome. What the new work does provide is a tested observational technique to distinguish these cases cleanly.

Technical caveats and limitations

What comes next

The immediate priority is to replicate this approach across a modest but representative sample of nearby AGN: the team suggests a dozen to a few dozen targets covering a range of luminosities and inclinations to establish whether Circinus is typical or exceptional. Observers will also combine AMI maps with ALMA’s cold‑gas tracers and with JWST’s spectroscopy to link dust morphology to the kinematics of molecular and ionized gas — the actual fuel and exhaust of black hole feeding. Such multiwavelength synthesis will tell us whether compact dusty disks routinely steal gas away from star formation or whether winds still dominate in ways that regulate galaxy‑wide growth.

Context for future facilities

The result underlines two broader trends. First, clever use of existing instruments — here, aperture masking on JWST — can yield breakthroughs without new hardware. Second, achieving a statistical understanding of AGN physics will likely require both high angular resolution and wide wavelength coverage, pushing the case for future space interferometers and next‑generation ground arrays. For now, Webb’s crisp look at the edge of a black hole is a reminder that some of the universe’s most consequential physics still hides on very small angular scales, and that observational ingenuity can bring it into focus.

Sources

- Nature Communications (research paper: "JWST interferometric imaging reveals the dusty disk obscuring the supermassive black hole of the Circinus galaxy")

- University of South Carolina (research group of Enrique López‑Rodríguez)

- Space Telescope Science Institute (NIRISS instrument and AMI mode)

- NASA / James Webb Space Telescope (mission and press materials)

- arXiv preprint: "JWST interferometric imaging reveals the dusty disk obscuring the supermassive black hole of the Circinus galaxy"

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!