Reassessing M31-2014-DS1: Why Andromeda’s 'Disappearing' Star Challenges Failed Supernova Theories

In 2014, astronomers monitoring the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) witnessed a rare and baffling cosmic disappearance. A massive yellow supergiant, designated M31-2014-DS1, began to fade rapidly, eventually vanishing from optical view. For years, the leading scientific consensus suggested this was a "failed supernova"—a dramatic event where a massive star bypasses a brilliant explosion and collapses directly into a black hole. However, a new study by Noam Soker of the Technion - Israel Institute of Technology suggests that this "vanishing act" may not be what it seems. By re-evaluating the physical parameters required for a failed supernova to occur, Soker argues that the scenario is mathematically unlikely and that the star may still be there, merely hidden behind a veil of cosmic dust.

The Failed Supernova Hypothesis

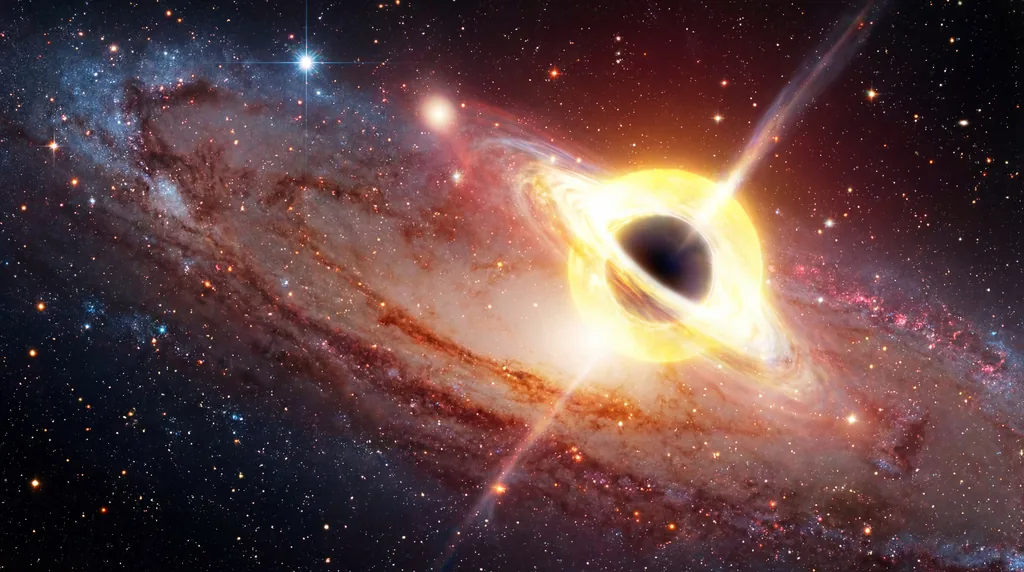

The concept of a failed supernova is a cornerstone of the modern "neutrino-driven" mechanism of stellar death. In this model, when the core of a massive star collapses, the resulting flood of neutrinos carries away a significant amount of mass-energy. This sudden loss of gravitational pull causes the star’s outer layers to expand. While most of the star collapses into a black hole, a small fraction of the envelope is ejected into space, with some material eventually falling back toward the newly formed singularity. This "fallback" material is theorized to form an accretion disk, powering faint jets and a low-luminosity transient event that lacks the brilliance of a standard supernova.

For M31-2014-DS1, researchers had previously proposed that this exact sequence of events occurred, leaving behind a black hole of roughly five solar masses. The appeal of this theory lies in its ability to explain why some of the universe's most massive stars seem to disappear without the expected pyrotechnics. It also helps explain the "missing red supergiant" problem—the observation that we see fewer high-mass supernova progenitors than stellar evolution models predict.

The Challenge of Fine-Tuning

In his latest research, Noam Soker challenges the feasibility of this model, characterizing it as a "failed failed-supernova scenario." According to Soker, the specific conditions required to match the observations of M31-2014-DS1 are incredibly narrow and physically improbable. The failed-supernova model requires that less than 1% of the bound fallback material actually be accreted by the black hole. If more material were consumed, the resulting jets would be far more energetic than what was observed in Andromeda.

Soker points out a glaring contradiction in the timing of this event. The proposed model suggests that accretion-powered jets must remain active for over a decade to explain the light curve, yet these same jets must somehow fail to shut down the inflow of gas for the same duration. "I find this fine-tuned requirement unlikely," Soker writes in his analysis, noting that the physical feedback loops between accreting gas and outgoing jets typically regulate such systems much more aggressively. The likelihood of a system maintaining such a delicate, ten-year-long imbalance is, in Soker’s view, nearly zero.

Convection and Angular Momentum Fluctuations

A significant portion of Soker's critique focuses on the role of pre-collapse convection within the yellow supergiant. Before a star collapses, its outer layers are a boiling cauldron of convective cells. These cells possess stochastic—or random—angular momentum. When the star collapses, this "swirl" doesn't just disappear; it dictates how the fallback material interacts with the black hole.

Soker argues that even if the star as a whole was rotating slowly, the internal turbulence would be enough to form intermittent accretion disks. These disks would inevitably launch jets through a process Soker identifies with the Jittering Jets Explosion Mechanism (JJEM). "The fallback material possesses large angular-momentum fluctuations due to the pre-collapse envelope convection," Soker explains. His calculations suggest that these fluctuations would produce jets energetic enough to trigger a much brighter explosion, rather than the faint, fading glow observed in 2014. The fact that M31-2014-DS1 did not explode brilliantly suggests that a core-collapse event might not have happened at all.

Radiative Discrepancies and Alternative Scenarios

Beyond the mechanics of accretion, Soker identifies a discrepancy in the observed light. In a failed-supernova scenario, the interaction between the outgoing jets and the surrounding stellar gas should produce significant radiation as the material cools. However, Soker’s analysis found that the expected radiation from such a cooling zone would be at least an order of magnitude higher than the values detected by telescopes. This mismatch further weakens the case for a black hole birth.

So, if not a failed supernova, what happened to the star? Soker points toward an alternative: a Type II Intermediate-Luminosity Optical Transient (ILOT). In this scenario, the star is part of a binary system that underwent a violent interaction or a partial merger. Such events can eject massive amounts of gas that quickly condense into dust. This dust acts as a cosmic "shroud," blocking the star’s light and making it appear to have vanished. "Fading is due to dust ejection in a violent binary interaction," Soker suggests, noting that this explanation fits the observed data without requiring "unlikely fine-tuned parameters."

Implications for Stellar Evolution

The debate over M31-2014-DS1 has profound implications for how we understand the life cycles of the most massive stars in the universe. If failed supernovae are as rare as Soker suggests, it would mean that most massive stars do indeed end their lives in bright explosions, and our current "neutrino-driven" models may need significant revision. It would also suggest that the "missing" progenitors are not disappearing into black holes, but perhaps are being obscured by their own late-stage mass loss or binary interactions.

Soker’s work aligns with other recent studies, such as those by Beasor et al. (2026), which utilize data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Submillimeter Array (SMA). These observations have failed to detect the high-energy signatures—such as specific X-ray fluxes—that one would expect from a newly formed black hole actively accreting matter. Instead, the infrared data suggests a non-spherical distribution of dust, a hallmark of binary star interactions rather than the more symmetric collapse of a single star.

What’s Next for the Andromeda Mystery

The ultimate test of Soker’s "failed-failed-supernova" theory will be time. If the star is merely hidden behind a shell of dust ejected during a binary interaction, that dust will eventually expand and thin out, or the star will move beyond the shroud. Soker has previously predicted that M31-2014-DS1 will eventually reappear, a "resurrection" that would definitively disprove the black hole collapse theory.

Future research will focus on long-term monitoring of the site in infrared and radio wavelengths. As telescopes like the JWST continue to peer through the dust of the Andromeda Galaxy, astronomers hope to find the "smoking gun"—either the faint, persistent heat of a hidden binary system or the unmistakable silence of a black hole. For now, the case of the vanishing supergiant remains a cautionary tale about the complexities of stellar death and the dangers of assuming that when a star disappears, it is gone for good.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!