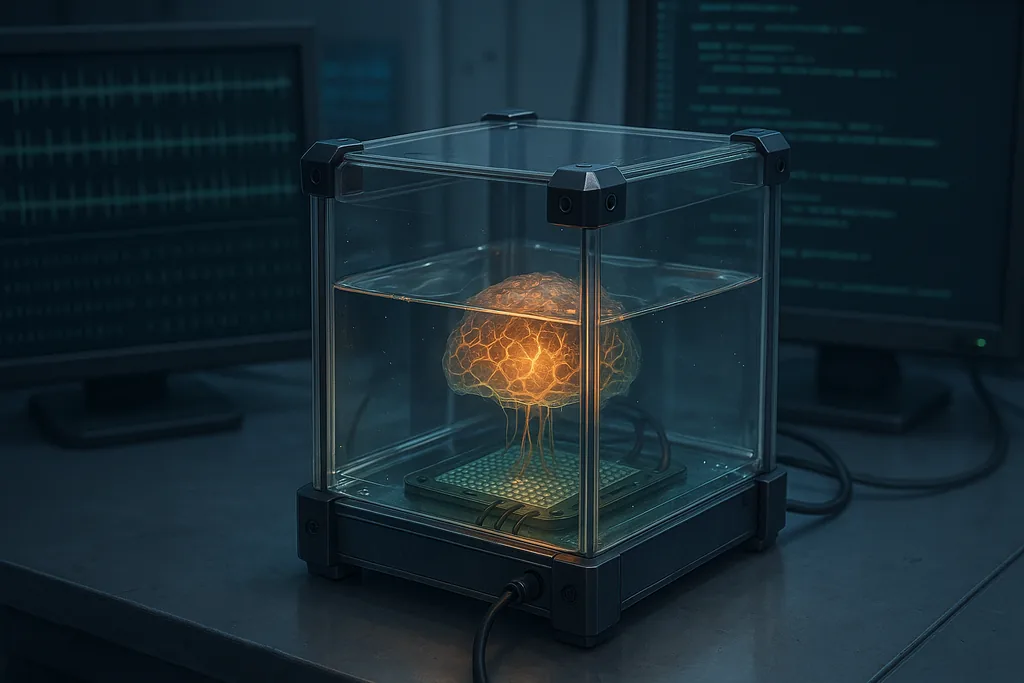

Lede: a living proof-of-concept

On a conference floor in Barcelona in March 2025 a compact box drew more than curiosity: it contained living human neurons kept alive and linked to silicon that the makers called a commercial "biocomputer." The device, known as CL1, builds on experiments where cultured neurons learned to play the arcade game Pong and later performed rudimentary speech recognition—proofs of principle that human brain cells can be coaxed into doing computation when paired with electrodes and software. Those experiments, and the business plans that followed, have pushed a quiet but fast-moving research area into headlines and policy debates.

From Pong and reservoir computing to desktop biocomputers

The field’s public origin story often points to a 2022 Neuron paper in which a system named DishBrain used networks of cultured cortical neurons—derived from human stem cells and from rodents—mounted on high-density multielectrode arrays to interact with a simulated Pong environment. In that closed-loop setup, patterned electrical stimulation supplied the game state as "sensory" input and the neurons’ firing guided the paddle; cultures adjusted their activity in ways the authors described as learning. The experiment was not a sentient mind, but it demonstrated that living neural tissue can be placed in a feedback loop and change its responses to achieve a task.

Other academic teams quickly followed. A group at Indiana University published a Nature Electronics paper showing a brain‑organoid reservoir computing system—nicknamed Brainoware—that recognized speakers from short vowel sounds and solved simple nonlinear prediction tasks after a short training period. These demonstrations used brain tissue as an adaptive, low‑energy substrate inside a hybrid system where digital readout layers interpret neural activity.

How organoids and electrode arrays do 'computation'

At the technical level these setups share a simple architecture: populations of neurons are grown from stem cells into clusters or organoids and sit on or near multielectrode arrays (MEAs). The MEA reads spike trains—the neurons’ electrical signals—and can also deliver precisely timed pulses that act as inputs or rewards. Researchers translate data (a game state, a sound clip, sensor output) into stimulation patterns, let the living network respond, and then use machine‑learning methods to decode the neural activity back into outputs. The system’s "learning" comes from the tissue’s intrinsic plasticity: neuronal connections strengthen or weaken, changing the network’s response patterns without rewriting software.

Commercialisation and the rise of 'wetware-as-a-service'

What was academic curiosity has become a market hypothesis. Startups and university teams now pitch organoid-based hardware and cloud access to it. Cortical Labs—one of the pioneers behind DishBrain—publicly unveiled a desktop biocomputer, the CL1, in 2025 and described plans for on‑premise units and cloud access that its marketing calls "wetware-as-a-service." Other companies and research platforms offer remote access to organoid arrays so labs can run experiments without cultivating tissue on site. Advocates point to potential advantages: energy efficiency for certain adaptive tasks, human‑relevant models for drug screens, and new experimental tools for neuroscience.

Short-term uses: drug testing, models and hybrid sensors

Most experts see nearer-term value in biomedical and scientific applications rather than replacing datacenter GPUs. Organoid platforms let researchers test drugs directly on human‑derived neural tissue, study development and disease mechanisms, and reduce animal testing. Hybrid systems have also been proposed for specialised sensing and robotics where low‑power adaptive controllers could matter. Several teams are exploring classification tasks—speech or tactile signals, or chaotic time‑series prediction—that demonstrate capability while remaining far from general intelligence.

Ethics, semantics and governance

The technology’s rapid advance has outpaced many existing ethical frameworks. When the DishBrain paper used the language of "sentience" it provoked immediate pushback and a scholarly debate about terms, precaution and the moral significance of lab‑grown neural tissue. Ethicists have urged clarity—distinguishing responsiveness, learning and information processing from phenomenal consciousness—and called for updated oversight that covers consent, donor rights, stewardship of tissue, and the possibility (however remote today) of morally relevant experiences in future systems. National bodies and academic reviews have recommended governance steps: refine consent processes, develop criteria to assess sentience potential, and coordinate international guidance so commercialisation does not outstrip safeguards.

Two dynamics make the ethics discussion urgent. First, companies aiming to commercialise biocomputers have a business incentive to use evocative language that attracts funding and customers. Second, the biological substrate is not just code; it is human‑derived material that carries donor and societal concerns about identity, reuse and dignity. Many ethicists recommend rules tailored to the technology’s specific risks instead of repurposing frameworks designed for classical biomedical research.

Scientific limits and contested claims

Beyond ethics, technical claims must be scrutinised. Demonstrations to date show specialised, small‑scale tasks and rely on hybrid architectures where classical hardware still does heavy lifting (encoding inputs, decoding outputs). Researchers stress that organoids are not small brains: they lack the layered, long‑range connectivity and developmental context of an intact human brain. Reproducibility across labs, the long‑term stability of organoid networks, and the engineering needed to scale them into reliable devices remain open problems. Some proponents see organoids as complementary to silicon—offering sample‑efficient learning and energy advantages for specific problems—rather than as a direct substitute for conventional computing.

The road ahead: calibrated optimism

What matters now is less a binary question of whether a "brain in a box" can be built, and more a policy‑science problem: how to accelerate the useful, low‑risk applications while bounding harms and clarifying public expectations. That means funders, regulators and research communities must agree on consent standards for donor tissue, transparency about what living systems can and cannot do, and shared metrics for assessing any emergent moral status. Parallel technical work—improving reproducibility, non‑invasive stimulation, and standardized MEA interfaces—will determine whether organoid computing stays a laboratory novelty or becomes a dependable tool for medicine and specialised computation.

In short: the experiments of the last few years show that living human neural tissue can be used as part of hybrid computational systems, and companies are moving to productise those ideas. Whether society treats that as an ethically fraught frontier or a pragmatic new lab instrument will depend on the openness of the research community, the strength of governance, and the realism of public discourse about what the biology actually does.

Sources

- Neuron (Kagan et al., "DishBrain" — in vitro neurons learn and exhibit adaptive behaviour).

- Nature Electronics (Guo et al., "Brain organoid reservoir computing").

- Indiana University (Brainoware research and press materials).

- University of Bristol (organoid Braille recognition / encoding strategies, arXiv preprint).

- Nature Reviews Bioengineering and National Academies reports on organoid ethics and governance.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!