Why 'beyond bans: rebuilding teaching' matters now

When campus leaders talk about blocking Wi‑Fi, confiscating devices or locking students into supervised labs, they are often reacting to a clear fear: AI can generate polished work in seconds and upend long-standing assessment practices. The phrase beyond bans: rebuilding teaching points to a different answer. Rather than treating tools as the enemy, this approach asks universities to redesign courses, assessments and governance so graduates learn to use, evaluate and critique AI—skills they will need in professions already saturated with algorithmic assistants.

This is not a small curricular tweak. It touches teaching practice, institutional procurement, accessibility and academic integrity. It implies training faculty to redesign assignments, investing in human grading capacity, and creating transparent rules for disclosure and verification. Those are structural choices that require funding, time and a shift away from policing toward pedagogy.

Practically, that means asking new questions: Which courses must ban AI for safety and clinical competence? Which ones should require explicit attribution and verification? How do we assess learning when a student can produce a near‑publishable draft with a single prompt? The answers are pedagogical, not technological—rooted in student work that makes thinking visible.

Beyond Bans: Rebuilding Teaching — Redesigning assessment and learning

Redesigning assessment is the core of beyond bans: rebuilding teaching. Many current assignments reward a finished product delivered at a deadline; they do not require students to show the thinking behind it. That makes outsourcing—whether to another person or a model—tempting and easy. To protect learning, assessment must value process as much as product. Portfolios with version histories, short reflection memos, annotated bibliographies, and in‑class or live oral defenses let instructors evaluate judgment and method rather than surface prose.

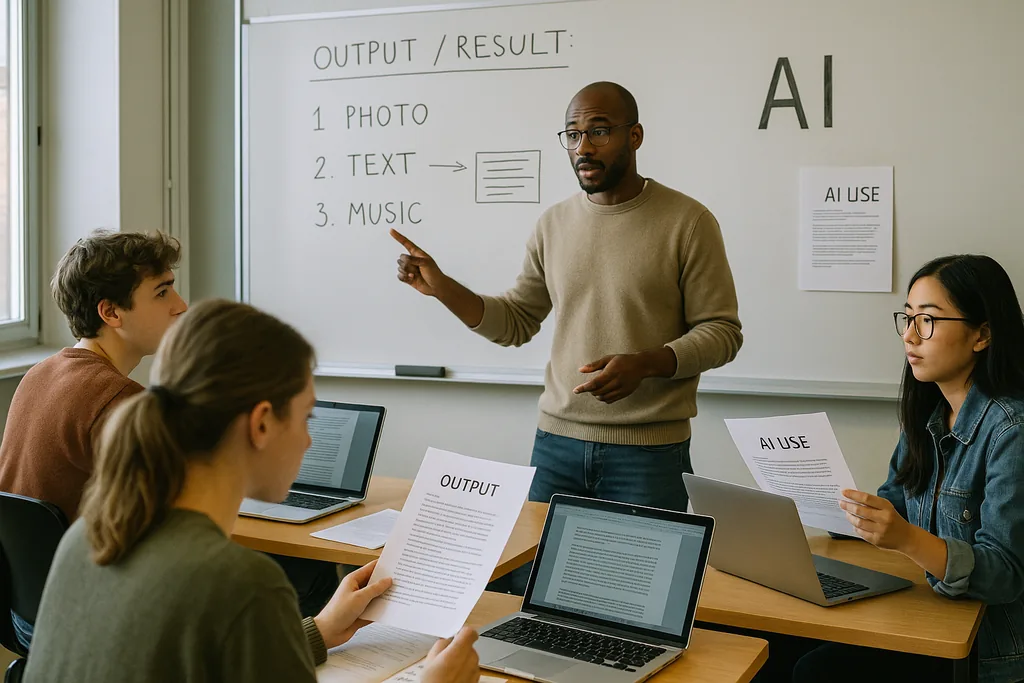

Integrating AI into this redesign means building verification into the rubric. Students should submit an "AI use" statement that lists prompts, model outputs retained, transformations performed and checks made against primary sources. In practice, that looks like a short, structured box on every submission: what tool was used, why, and how the student verified or corrected the output. When verification is graded, the incentive structure changes—students are rewarded for catching model errors, not obscuring them.

Assessment studios—faculty learning communities that co‑design assignments, rubrics and disclosure language—can help instructors translate these ideas into classroom practice. These studios also tackle domain specificity: the right verification task for a history paper differs from that for a software engineering assignment. Across disciplines, the same principle holds: make thinking audible and visible so tools become one input among many, not a replacement for mastery.

Beyond Bans: Rebuilding Teaching — Balancing AI assistance with critical thinking

Educators face a core pedagogical tension: how to allow students to use powerful assistants while still developing independent critical thinking. The solution lies in calibrated constraints and scaffolded practice. Start by teaching students how AI systems work—their strengths, failure modes, and typical hallucinations. Short, classroom demos that show when a model invents a citation or misstates a fact are more effective than blanket warnings. Students who learn to test and triangulate outputs internalize skeptical habits.

In the classroom, require students to defend choices in real time. Oral exams, live debugging sessions, teach‑backs, or short public presentations force students to demonstrate comprehension beyond a static text file. For code‑heavy work, annotated commits and live demos show that the student understands trade‑offs and can explain unexpected behavior. For essays, asking for a five‑minute spoken summary of an argument exposes gaps in comprehension that a written draft alone can hide.

Faculty development, capacity and fair assessment

Rebuilding teaching means investing in people. Assignments that foreground process require more interaction: feedback on drafts, structured critiques, and smaller evaluation ratios. That cannot happen at scale without funding for teaching assistants, grader training, writing centers and dedicated assessment redesign time. Institutions that attempt to curtail AI while leaving class sizes and manpower unchanged will only push the problem into corners.

When faculty are supported through assessment studios and small grants to redesign courses, the institution benefits twice: assessment becomes more authentic, and faculty gain practical skills for teaching in an AI‑mediated world. Training should cover not only technical literacy but also rubric design, prompt documentation, and methods for in‑class verification.

Policy architecture: procurement, disclosure and tiered rules

Policy should be clear, shared and enforceable. A pragmatic approach is tiered rules: clinical courses or high‑stakes professional competencies may reasonably ban certain tools; foundational or advanced courses may require disclosure and verification; specialized classes should teach domain‑specific integrations. Treating policy as a one‑size‑fits‑all ban is both impractical and unfair.

Procurement matters. Institutions should vet AI tools for accessibility, privacy, auditability and labor transparency before recommending them for classroom use. Create a vetted tool list and procurement standards so faculty and students can rely on options that meet institutional norms. Where consumer tools are used, instruct students never to upload sensitive data; where necessary, provide institution‑managed alternatives with proper safeguards.

Finally, incorporate sustainability and cost awareness. A "compute budget" model—where students have a limited number of queries or a set allotment of compute—teaches efficiency and ethical resource use. It mirrors real professional constraints and builds habits of trade‑off thinking that reflect workforce realities.

Assessing learning when AI can generate work

Assessment in an era of capable models requires moving from detection to design. Rather than relying primarily on plagiarism detectors, professors should redesign evaluations to make authentic work visible: staged submissions, oral defenses, annotated archives of sources and process logs. Machine‑generated text is easy to produce, but hard to defend under scrutiny. Assessment strategies that require explanation, citation checks and live problem solving reduce the value of outsourcing.

Rubrics should include verification as a scored category. Reward students for identifying errors in model outputs and for documenting how they fixed them. That turns an environment of temptation into an opportunity for skill building: students learn critical source evaluation, prompt craft and ethical citation practices. Over time, these habits become the learning outcomes universities can credibly claim.

Where detection is necessary, pair it with restorative practices. Use confirmed misconduct as a teaching moment that clarifies expectations and strengthens assessment design. The goal is not punitive surveillance but a system that aligns incentives with authentic learning.

Practical steps campuses can take this term

Universities do not need Faraday cages; they need a plan. Start with a tiered policy that maps course types to permitted practices. Launch assessment studios and offer small redesign grants. Pilot an AI literacy credential that covers bias, verification, privacy, citation and sustainability. Create a vetted tool list and procurement standard. Finally, invest in human capacity—TAs, writers' centers and instructor time—so redesigned assignments can scale.

These are practical, fundable measures. They acknowledge that technology is not going away and that protecting learning requires more than prohibition: it requires new designs, new skills and the political will to fund them. Beyond bans: rebuilding teaching is a program of work, not a slogan.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!