NASA’s Nuclear Propulsion Milestone: First Flight Reactor Tests Since the 1960s

In a move that signals a paradigm shift for long-duration space travel, NASA has successfully completed a comprehensive cold-flow test campaign of its first nuclear flight reactor engineering development unit in over fifty years. Announced on January 27, 2026, from Washington D.C., the milestone represents a critical advancement in Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) technology. Conducted at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, this series of tests provides the empirical foundation necessary to move beyond the limitations of chemical propulsion and toward the ambitious goal of sending human crews to Mars and the deep reaches of the solar system.

The Return to Atomic Propulsion

The history of nuclear propulsion at NASA is one of interrupted brilliance. During the 1960s, the Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application (NERVA) program demonstrated the immense potential of atomic energy for spaceflight, reaching high stages of technological readiness before the program was shuttered due to changing budgetary priorities and a shift in the agency's focus toward the Space Shuttle. The recent 2025-2026 test campaign marks the first time since that era that a flight-like nuclear reactor unit has undergone such rigorous engineering validation. This return to nuclear research is not merely a nostalgic revival but a strategic necessity driven by the complex requirements of the Artemis program and the eventual human mission to Mars.

The engineering development unit (EDU) at the heart of this campaign was manufactured by BWX Technologies, based in Richmond, Virginia. This full-scale, non-nuclear test article—standing 72 inches tall and 44 inches wide—serves as a high-fidelity surrogate for the reactors that will eventually power deep-space vessels. By partnering with industry leaders, NASA is leveraging modern manufacturing techniques to solve the thermal and structural challenges that stymied previous generations of engineers, ensuring that the next generation of rockets is as reliable as it is powerful.

Understanding Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP)

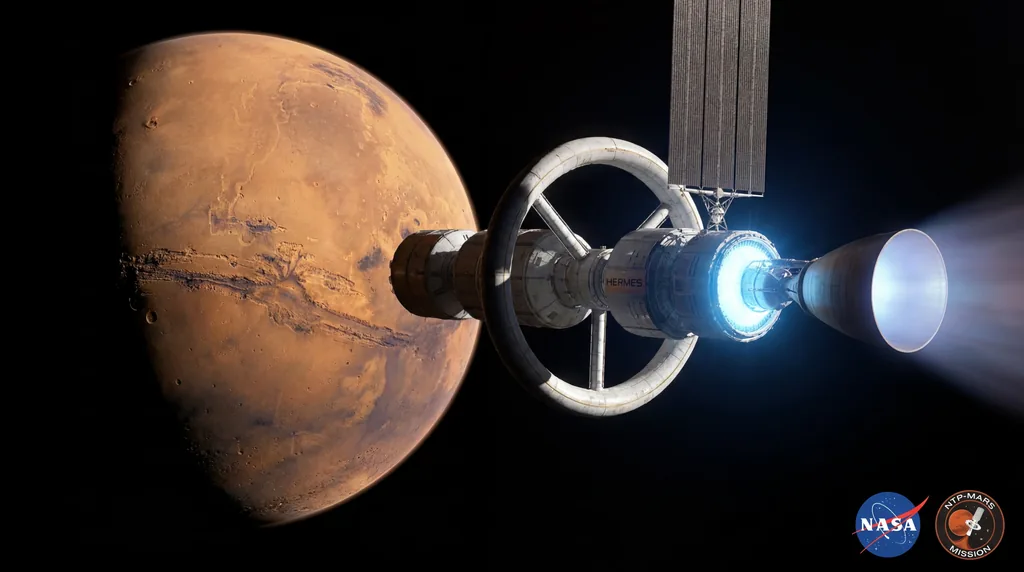

To appreciate the significance of these tests, one must understand how Nuclear Thermal Propulsion differs from the chemical rockets that have dominated the space age. Traditional rockets, such as the Space Launch System (SLS), generate thrust by combusting a fuel and an oxidizer. In contrast, an NTP system uses a compact nuclear reactor to generate extreme heat. This thermal energy is transferred to a propellant, typically liquid hydrogen, which expands rapidly and is exhausted through a nozzle at incredibly high velocities. Because the propellant is not burned but rather heated, NTP systems can achieve a specific impulse—a measure of fuel efficiency—two to three times higher than that of the best chemical engines.

The "cold-flow" designation of the recent Marshall Space Flight Center tests refers to the fact that no actual nuclear fission occurred during this phase. Instead, the team focused on the fluid dynamics of the system. Over the course of more than 100 individual tests, engineers pushed various propellants through the BWX Technologies unit at different pressures and temperatures to simulate operational conditions. This allowed the team to validate the reactor’s internal geometry and ensure that the propellant behaves predictably as it moves through the complex channels of the reactor core.

Technical Triumphs in Fluid Dynamics

One of the most critical findings of the campaign was the reactor’s resilience against flow-induced instabilities. In high-performance rocket engines, moving fluids can often interact with the engine's structure in ways that create destructive oscillations, vibrations, or pressure waves—phenomena that can lead to catastrophic hardware failure. The Marshall test engineers successfully demonstrated that the current reactor design is immune to these destructive forces across its entire operational range. By confirming the structural integrity of the unit under flow stress, NASA has cleared one of the most significant engineering hurdles on the path to a flight-ready system.

Jason Turpin, manager of the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office at NASA Marshall, emphasized the historical weight of these findings. "This test series generated some of the most detailed flow responses for a flight-like space reactor design in more than 50 years," Turpin stated. He noted that the data gathered would be instrumental in designing the flight instrumentation and control systems. Beyond the physics of the flow, the EDU served as a "pathfinder" for the manufacturing and assembly processes, proving that modern aerospace supply chains can handle the precision required for nuclear-integrated hardware.

The Mars Transit Advantage

The ultimate goal of this research is the drastic reduction of transit times for human missions to the Red Planet. Current chemical propulsion systems require a one-way trip of approximately nine months. With a fully realized NTP system, that duration could be slashed to four or six months. This reduction is not just a matter of convenience; it is a critical safety measure. Shorter transit times significantly reduce the crew’s exposure to solar and cosmic radiation, which are major health risks in deep space. Furthermore, it lessens the physiological toll of long-term microgravity on the human body, such as bone density loss and muscle atrophy.

Additionally, the high efficiency of nuclear propulsion allows for increased science payload capacity. Because less mass is dedicated to bulky chemical propellants, engineers can allocate more room for life support systems, scientific instruments, and high-power communication arrays. This increased mass-to-orbit capability ensures that when humans do reach Mars, they will have the tools necessary to perform high-impact science and establish a sustainable presence.

Integration with the Artemis Program and Beyond

The development of NTP does not exist in a vacuum but is closely tied to NASA’s broader lunar and Martian architectures. While the Artemis program currently relies on the SLS and the Orion spacecraft, the transition to a long-term lunar base will require the high-power capabilities that only nuclear energy can provide. This includes not only propulsion but also surface power. The synergy between the current EDU tests and the Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations (DRACO) initiative—a collaboration between NASA and DARPA—highlights a multi-agency commitment to securing American leadership in space nuclear technology.

Strategically, the use of nuclear propulsion ensures that the United States can maintain "agile" operations in cislunar space (the region between Earth and the Moon). As space becomes more congested and contested, the ability to maneuver large payloads quickly and efficiently becomes a matter of national importance. The data from the Marshall Space Flight Center provides a roadmap for the transition from experimental testing to operational deployment in the late 2020s and early 2030s.

Safety, Environmental Protocols, and Future Directions

The modern era of space nuclear research is governed by significantly stricter safety protocols than those of the 1960s. Central to this is the use of High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU). Unlike the highly enriched fuels used in the past, HALEU provides a safer, more stable fuel source that meets international non-proliferation standards while still offering the high energy density required for NTP. NASA and its partners are working closely with the Department of Energy to ensure that every stage of the nuclear lifecycle—from fuel fabrication to launch and eventual disposal—adheres to the highest safety and environmental standards.

Looking ahead, the success of the cold-flow campaign paves the way for "hot" testing, where the reactor will eventually be integrated with nuclear fuel for ground-based power runs. These future milestones will bring the agency closer to a full-scale flight demonstration. As Jason Turpin concluded, each of these technical successes "brings us closer to expanding what's possible for the future of human spaceflight." With the foundation laid at Marshall, the dream of a fast, efficient, and atomic-powered journey to the stars is no longer a relic of the mid-century, but a tangible reality of the near future.