On 27 January 2026 OpenAI published unusually detailed engineering notes explaining how the Codex CLI—the company’s command‑line coding agent—actually runs conversations, calls tools, and manages context.

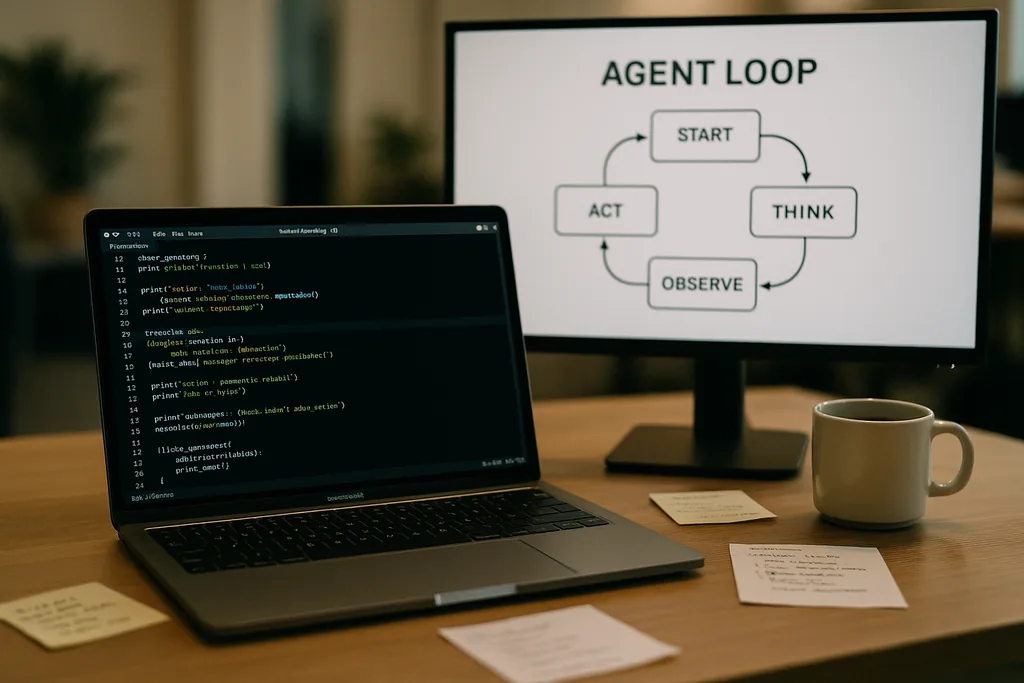

What the agent loop looks like

At the heart of Codex CLI is a simple repeating pattern engineers call the "agent loop": accept user input, craft a prompt, ask the model for a response, act on tool calls the model requests, append tool outputs to the conversation, and repeat until the model returns a final assistant message.

That pattern sounds straightforward, but the documentation unpacks many small design decisions that together shape performance and reliability. The prompt sent to the model is not a single blob of text; it is a structured assembly of prioritized components. System, developer, assistant and user roles determine which instructions take precedence. A tools field advertises available functions—local shell commands, planning utilities, web search and custom services exposed via Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers. Environment context describes sandbox permissions, working directories and which files or processes are visible to the agent.

Tool calls, MCP and sandboxing

When the model emits a tool call, Codex executes that tool in a controlled environment (its sandbox), captures the output, and appends the result to the conversation. Custom tools can be implemented through MCP servers—an open standard several companies have adopted—which let a model discover and invoke capabilities beyond a simple shell. The documentation also discusses specific bugs the team discovered while building these integrations—an inconsistent enumeration of MCP tools, for example—that had to be patched.

OpenAI notes that sandboxing and tool access are active areas for follow‑up posts. The initial documentation focuses on the loop mechanics and performance mitigation rather than the full threat model of agents with write access to a filesystem or network services.

Stateless requests, privacy choices and the cost of copying context

That inflation is not linear. Each turn adds tokens, and since every turn includes prior turns in full, prompt size tends toward quadratic growth relative to the number of turns. The team documents this explicitly and explains how they mitigate it with context compaction and prompt caching.

Prompt caching and exact prefixes

Prompt caching is a pragmatic optimization: if a new request is an exact prefix of a previously cached prompt, the provider can reuse computation and return results faster. But caches demand rigidity. Any change to available tools, a model switch, or even a sandbox configuration tweak can invalidate the prefix and turn a cache hit into a costly miss. OpenAI engineers warn that developers should avoid mid‑conversation reconfiguration when they need consistent latency.

Cache hits depend on exact prefix matching, so sensible practices include pinning tool manifests and keeping model selection constant within an ongoing interaction. When cache misses occur frequently, the system degrades to full reprocessing on every call—exactly when developers expect the agent to feel snappy.

Context compaction: compressing the past without losing meaning

To manage token growth, Codex implements automatic context compaction. Rather than leaving it to a user command, the CLI calls a specialized API endpoint that compresses older conversation turns into an encrypted content item while retaining summarized knowledge the model needs to proceed. Earlier versions required manual user compaction; the newer approach pushes the process into an API call that preserves the model’s working memory.

Compaction reduces token cost but introduces a few subtleties: summaries must be faithful enough to prevent downstream hallucination, encryption props need to match privacy constraints, and compaction heuristics must decide which pieces of the state are essential versus expendable. The documentation flags these as open engineering choices rather than settled designs.

Practical limits and developer experience

OpenAI’s notes are candid about strengths and weaknesses. For straightforward tasks—the kind of scaffolding, boilerplate or rapid prototyping that coding agents excel at—Codex is fast and useful. For deeper, context‑heavy engineering work the model hasn’t seen in its training data, the agent is fragile. It will generate promising scaffolds, then stall or output incorrect steps that need human debugging.

Engineers testing Codex internally found that the agent can accelerate initial project creation dramatically but cannot yet replace the iterative, expert debugging that solid engineering requires. The team also confirmed that they use Codex to build parts of Codex itself—a practice that raises interesting feedback questions about tools trained on their own outputs.

Why OpenAI opened this up—transparency, competition and standards

Publishing a deep dive into a consumer product’s internal engineering is notable coming from a company that has typically guarded its operational details. OpenAI’s disclosure coincides with a broader ecosystem push toward agent standards: Anthropic and OpenAI both support MCP for tool discovery and invocation, and both publish CLI clients as open source so developers can inspect behavior end to end.

The transparency serves several audiences. Developers get implementation patterns and practical advice for building reliable agents. Security-minded engineers can scrutinize sandbox and tool‑access trade‑offs. Competitors and the standards community can iterate faster because they do not need to reverse‑engineer client behavior to interoperate.

Operational advice for teams using coding agents

- Pin models and tool manifests within a session to maximise prompt cache hits and stable performance.

- Use context compaction proactively for long tasks to control token costs and avoid runaway prompt growth.

- Limit agent permissions and isolate writable folders in sandboxes to reduce accidental or malicious side effects.

- Expect and budget for manual debugging: agents accelerate scaffolding and iteration, but they do not yet replace expert reasoning on complex codebases.

What comes next

The engineer who wrote the post signalled follow‑ups that will cover the CLI’s architecture in more depth, tools implementation, and the sandboxing model. Those future entries will matter: as agents gain deeper access to developers’ environments, the mechanics of safe execution, provenance and verifiable tool invocation will determine whether teams adopt them as assistants or treat them as risky curiosities.

For now, OpenAI’s notes convert some of the mystique around coding agents into concrete knobs and levers. That shift makes it easier for engineering teams to plan around known trade‑offs—performance, privacy, and fragility—rather than discovering them the hard way during production outages.

Codex CLI’s documentation is an invitation: read the implementation, test the edge cases, and design workflows that accept the limits while leveraging the clear benefits. In an industry racing to put agents into everyday developer tools, clarity about failure modes is the rarest and most useful commodity.

Sources

- OpenAI (documentation: "Unrolling the Codex agent loop")

- Anthropic (Model Context Protocol specification and Claude Code materials)

- OpenAI engineering repositories and Codex CLI implementation notes