Decoding the Inner Shadow: How Accretion Geometry Shapes Our View of M87* and Sagittarius A*

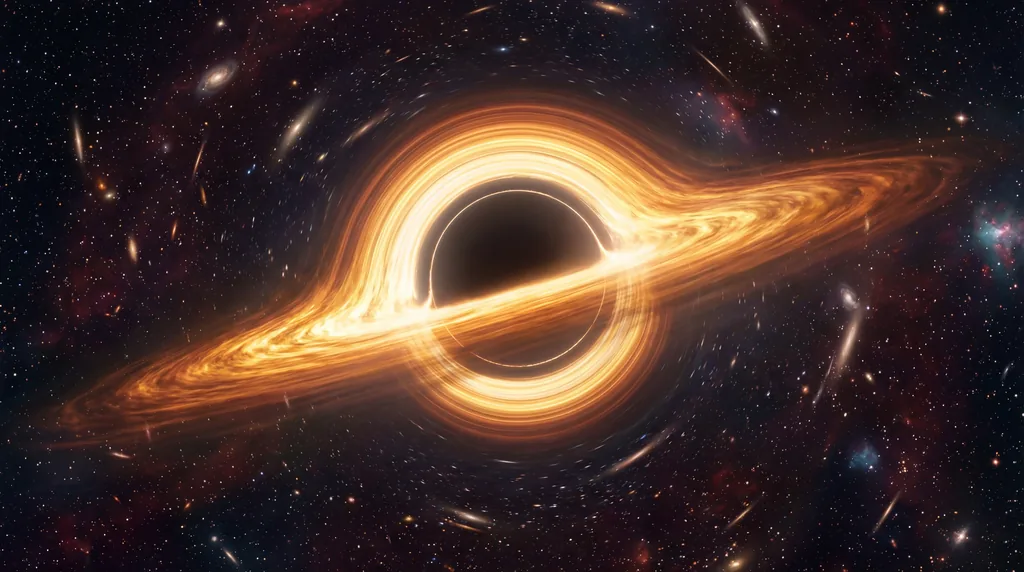

In the pursuit of understanding the most extreme environments in the universe, the silhouette of a black hole has become a central icon of modern astrophysics. Since the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration released the first image of the supermassive powerhouse at the center of the M87 galaxy in 2019, followed by the image of our own Milky Way’s Sagittarius A* in 2022, scientists have moved beyond mere detection. The current frontier involves using these "shadows" to measure fundamental properties—mass, spin, and even electric charge. However, a new study led by researchers Dominic O. Chang, Daniel C. M. Palumbo, and Julien A. Kearns suggests that these measurements are deeply intertwined with the geometry of the light-emitting gas surrounding the event horizon. Their research reveals that unless we correctly account for the thickness and orientation of the accretion flow, our interpretation of these cosmic giants could be significantly skewed.

The landmark images produced by the EHT provided the first visual evidence of a photon ring—a bright circle of light formed by photons that have been gravitationally lensed around the black hole. While these images confirmed the basic predictions of General Relativity, they represent only the beginning. The next generation of observatories, including the Next-Generation Event Horizon Telescope (ngEHT) and the space-based Black Hole Explorer (BHEX), aim to resolve finer details within these structures. This transition from capturing basic ring-like morphologies to high-resolution mapping requires a sophisticated understanding of how the surrounding matter, or accretion disk, contributes to the light we see.

The Physics of the Shadow and the Inner Shadow of a Black Hole

Central to the research is the distinction between two critical features: the black hole shadow and the inner shadow. While often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they represent different physical phenomena. The standard shadow is the large central dark region formed by the photon ring’s critical curve, where light rays asymptote to unstable orbits. In contrast, the "inner shadow" is a smaller, even darker area nested within the main shadow. It appears primarily in models where emission is confined near the equatorial plane, such as in magnetically arrested disks. The inner shadow is essentially the direct lensed image of the event horizon’s edge, providing a much tighter constraint on the black hole’s metrics than the broader shadow alone.

To investigate how these features might be used to decode black hole parameters, Chang and his colleagues utilized the Reissner-Nordström metric, which describes a non-rotating black hole with mass and charge. By varying the mass and charge, they could observe how the size and shape of both the shadow and the inner shadow shifted. However, their primary contribution lies in exploring how the emission geometry—the "co-latitude" or the angular spread of the glowing gas—interacts with these features. They discovered that the perceived size of these shadows is not just a product of gravity, but a complex interplay between the black hole’s spacetime and the physical structure of the accretion disk.

An accretion disk fundamentally alters our view through several relativistic effects. Gravitational lensing bends light paths to create the characteristic ring, while Doppler boosting causes the side of the disk moving toward the observer to appear much brighter than the side moving away. Furthermore, gravitational redshift shifts light to longer wavelengths as it escapes the intense pull near the event horizon. The researchers found that "thick" accretion disks—those where light is emitted from a broader range of angles—can obscure the inner shadow or change its apparent diameter. This poses a significant challenge: if an observer assumes a thin disk model when the reality is a thick flow, the calculated mass or charge of the black hole could be fundamentally incorrect.

The Challenge of Accretion Geometry and Parameter Degeneracy

The methodology of the study involved simulating images of black hole accretion flows across a wide parameter space. By testing different observer inclinations—the angle at which we view the disk—the team found that the ability to constrain black hole parameters is highly sensitive to our knowledge of the emission source. Specifically, they noted that independent measurements of both the shadow radius and the inner shadow radius are necessary to "break the degeneracy" between variables like charge and inclination. Degeneracy occurs when two different physical setups—for example, a black hole with high charge viewed at one angle versus a black hole with low charge viewed at another—produce nearly identical images.

The findings of Chang, Palumbo, and Kearns highlight that while future observatories will provide the resolution needed to see the inner shadow, the data will only be as good as the models used to interpret them. "We confirm previous studies that have shown that independent radii measurements... can constrain black hole parameters if the viewing inclination is known," the authors note, but they warn that this is only possible if the "true emission geometry" is assumed. For a system like M87*, which is viewed almost pole-on, the challenges differ from Sagittarius A*, which may have a more complex or edge-on orientation. The study suggests that the thickness of the disk can "bleed" light into areas that would otherwise be dark, effectively shrinking the apparent size of the inner shadow and complicating the measurement of the event horizon's influence.

Future Directions and the Role of ngEHT and BHEX

The implications for the field are profound, particularly as the ngEHT moves toward its operational phase. The ngEHT is expected to produce sharper, higher-resolution images and even dynamic movies of M87* and Sagittarius A*. By adding more telescopes to the global array and quadrupling the bandwidth, the ngEHT will achieve resolutions down to 13 microarcseconds. This level of detail will allow scientists to map magnetic fields and detect "hot spots" within the accretion flow. However, the work by Chang’s team suggests that the ngEHT’s success in testing General Relativity will depend on our ability to simultaneously model the plasma physics of the accretion disk alongside the gravitational physics of the black hole.

Beyond ground-based arrays, the Black Hole Explorer (BHEX) represents the next leap in high-fidelity imaging. By placing a telescope in space, researchers can bypass the atmospheric interference that limits ground-based observations, allowing for even higher frequency imaging. This would provide a clearer look at the "photon ring," the thin sub-structure within the shadow that is less affected by the messy physics of the accretion disk. The research team emphasizes that the combination of ground and space observations will be vital to isolating the pure gravitational signature of the black hole from the luminous "contamination" of the surrounding gas.

Ultimately, the study serves as a cautionary yet optimistic roadmap for the next decade of black hole research. By identifying the "inner shadow" as a direct signature of the event horizon, the researchers have provided a new metric for precision gravity tests. As we refine our models of thick and thin accretion flows, our ability to use M87* and Sagittarius A* as laboratories for the strong-field regime of General Relativity will only grow. The path to decoding the most mysterious objects in the cosmos lies in the subtle shadows they cast—provided we are careful enough to account for the light that defines them.