Lede: A classroom and a crossroads

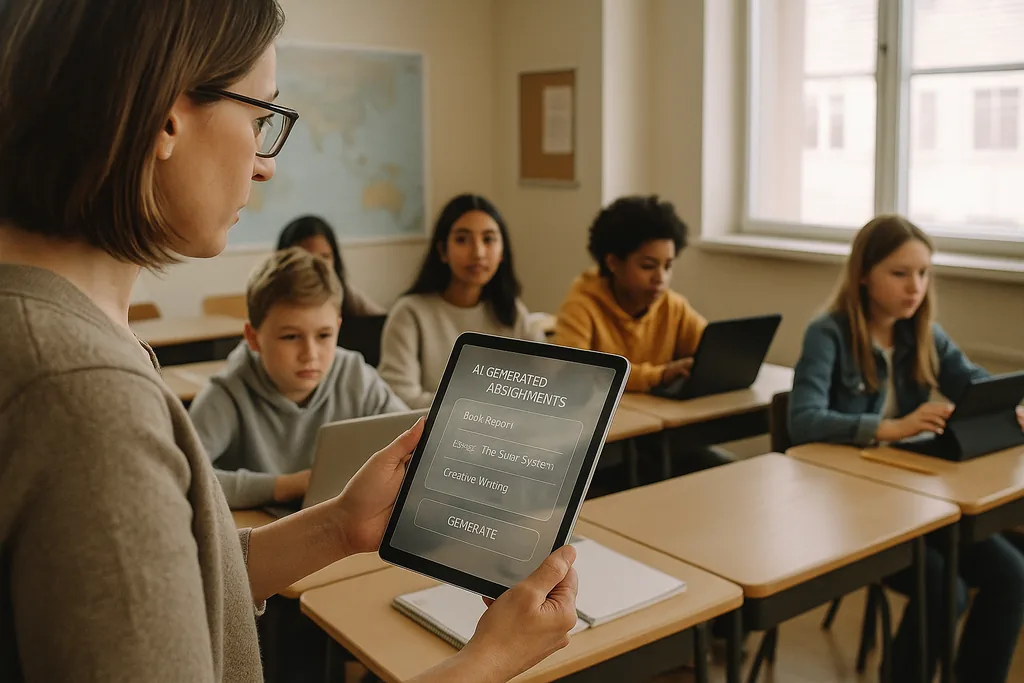

In a brightly lit middle-school classroom in suburban Ohio this month (January 2026), a teacher taps through an AI platform that generates individualized math practice for each student. The scene — touted by vendors as an efficient way to close learning gaps and free teachers for small-group instruction — now sits at the center of an intense debate. Across the United States, districts flush with post-pandemic technology budgets and squeezed by teacher shortages are contracting with EdTech vendors; simultaneously, a growing chorus of educators, civil-rights advocates and international agencies is arguing that the costs of rushing into AI may be far greater than the benefits.

The data problem: bias baked into learning tools

When an algorithm routinely assigns lower scores or more frequent interventions to the same demographic groups, the effect is not merely a technical bug: it becomes an institutional mechanism that hardens inequality. School leaders face a legal and ethical dilemma because procurement choices — which platforms to buy, which data to collect, how long to retain it — determine which students will be subject to automated judgements and which will not.

Pedagogy and the 'black box' problem

Beyond bias and privacy, teachers worry about the long-term educational consequences of outsourcing cognitive work to opaque systems. Generative AI can produce a passable essay or solve a problem step-by-step, but when students rely on the machine to generate ideas, draft arguments, or outline solutions, the deliberate cognitive struggle that develops critical thinking can atrophy. Learning is not only about correct answers but about the process of thinking — showing one’s work, wrestling with counterarguments, revising drafts — and many current AI tools obscure that process.

Compounding this is the ‘black box’ nature of many models. Students and teachers rarely see how a recommendation or a grade was derived, which makes it difficult to turn an automated output into an instructional moment. Federal education guidance has emphasized keeping a human in the loop for consequential decisions for precisely this reason: accountability, interpretability and the educator’s professional judgement remain essential to sound pedagogy.

Surveillance, consent and fractured trust

AI in schools often brings with it new forms of surveillance. Proctoring software, behavior analytics and platform telemetry create records of students’ faces, movements, typing patterns and time-on-task. Those records are valuable to vendors and school administrators but also sensitive: who can access them, how long they are stored, and whether they are used to develop new commercial products are questions many districts have yet to answer comprehensively.

For families and teachers, the presence of pervasive monitoring can erode trust. Students who know they are being continuously observed are likely to change how they behave in ways that harm learning: avoiding legitimate off-task behaviour that can lead to creative exploration, or feeling anxiety that undermines performance. Consent is complicated in K–12 settings because minors cannot always provide fully informed agreement, and parents may not be given clear, comparable choices when vendors are bundled into district-wide contracts.

Inequitable rollouts and a new digital divide

Far from leveling the playing field, AI can deepen an existing divide. Wealthier districts are able to pilot robust products, require privacy protections in contracts, and fund professional development so teachers can integrate tools thoughtfully. Under-resourced districts may accept free or discount-tier services that come with weaker privacy guarantees, less transparency and minimal training. The result: two tiers of AI in education — premium, well-supported deployments in some schools, and poorly governed, lightly supported systems in others.

That split not only widens achievement gaps but produces divergent educational models. In affluent districts, AI can serve as an assistant to well-trained educators; elsewhere, it risks becoming a substitute for investment in teachers and curricula.

Grassroots resistance and a call for "digital sanity"

Pushback is forming at multiple levels. Teacher groups, parent coalitions and civil-rights organizations are asking districts to slow procurement, mandate pilots, and require independent audits for bias and privacy harms. Many advocates are not anti-technology; they are pro-pedagogy. Their demand is for a sober, evidence-driven process: pilot small, measure learning outcomes, test for disparate impacts, and involve teachers and families in procurement decisions.

From procurement to accountability: concrete steps

Moving from rapid adoption to responsible use requires a shift in priorities. Districts should treat AI procurement as a public-policy decision rather than a routine IT purchase. That means asking vendors for clear documentation on data sources and bias-mitigation practices, requiring explainability for any decision that affects grading or discipline, and specifying contractual limits on data reuse. Investments in teacher training and curricular integration must accompany any rollout; software licenses without human capacity will underdeliver and risk harm.

Regulators and funders have roles to play. Public agencies can provide independent evaluation frameworks, fund pilot studies that measure both learning gains and equity outcomes, and issue procurement guidelines that prioritize privacy and transparency. Without those systemic supports, districts will continue to face asymmetric bargaining power with large vendors and an uneven landscape of protections.

What is at stake

The choices made in procurement offices and school boards now will shape how an entire generation experiences learning. AI has the potential to amplify good teaching and personalise instruction at scale — but it also has the capacity to formalize discrimination, entrench surveillance and dilute the intellectual labor that schools are meant to foster. The question for education leaders is not whether to use AI, but how to do so in ways that protect students’ rights and strengthen pedagogy rather than replace it.

As districts sign multi-year contracts, they are not only buying software; they are endorsing a vision of what schooling should be. The safest path is pragmatic and human-centered: pilot, measure, require transparency, invest in people, and make equity the default constraint on any technical deployment.

Sources

- Center for Democracy & Technology — report on harms and risks of AI in education

- American Civil Liberties Union — analysis of AI and inequity

- U.S. Department of Education — "Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Teaching and Learning" report

- UNESCO — "Guidance for generative AI in education and research"